CAM Houston hosts It is what it is. Or is it? this summer, a group show that considers how artists are using and making readymades. As the art form nears its 100th anniversary, the show surveys how it has changed.

The art critic and historian Tony Godfrey argues that “objects cannot just be objects in our society: we overload them instinctively with meanings and significance.” The interplay between objects and people, and the way in which society consumes those objects, has fascinated both cultural historians and artists for centuries, with Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) famously taking objects and re-presenting them as artworks in the early 20th century.

Duchamp’s first readymade was a bicycle wheel fixed on a stool. Bicycle Wheel (1913) was derided by much of the art world and subsequent works, such as Fountain (1917), elicited the same response. Critics of the day considered these works to be indecent and immoral, and they were lambasted by the press. Duchamp, describing Fountain, which was a white porcelain urinal signed with his pseudonym “R. Mutt” said that “he took an ordinary article of life, placed it so its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.” It’s this decisive re-shaping of the traditional usage of the language of art that defines the readymade.

As time has progressed, the readymade has become an integral form of art and art production, and Bicycle Wheel could now be considered one of the seminal pieces of work in the art historical canon. In his influential text of 1969, Art After Philosophy, Joseph Kosuth credits Duchamp with “giving art its own identity [as with] the unassisted Readymade, art changed its focus from the form of language to what was being said.” It is from this historical basis that It is what it is. Or is it? opened on 12 May at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston. The exhibition takes the readymade as a starting point from which to explore the work of 18 contemporary artists, and investigates the way in which the readymade has influenced and is utilised by them in their own work. The readymade is nearing its 100th anniversary and, as such, the curator Dean Daderko felt it was time to re-examine it and its continuing influence in the contemporary art world: “Its simplicity, both materially and conceptually, presents illuminating ways in which to assess our contemporary moment; it’s an ideal and malleable form that can be pressed into service to address the complex and multivalent global contexts we exist in.”

The selected artists are diverse in their practice and form of production; it is a mix which lends itself to the context of the show as the readymade is a varied and complex form. It presupposes the audience’s ability to think outside art historical pedagogy and to take pleasure in the basic forms of everyday life. Unsurprisingly, the readymade was revolutionary at the time, and a precursor for conceptual art as we know it. Daderko says that, with regard to Duchamp: “He doesn’t see the work of art as an endgame. It’s a springboard for other intensities and positions to be developed, a process. He established space for productive ambiguity and challenge within artistic production, and I see that as a position that appeals to many artists now … what’s the use in establishing a hierarchy if one only needs to break it down later?”

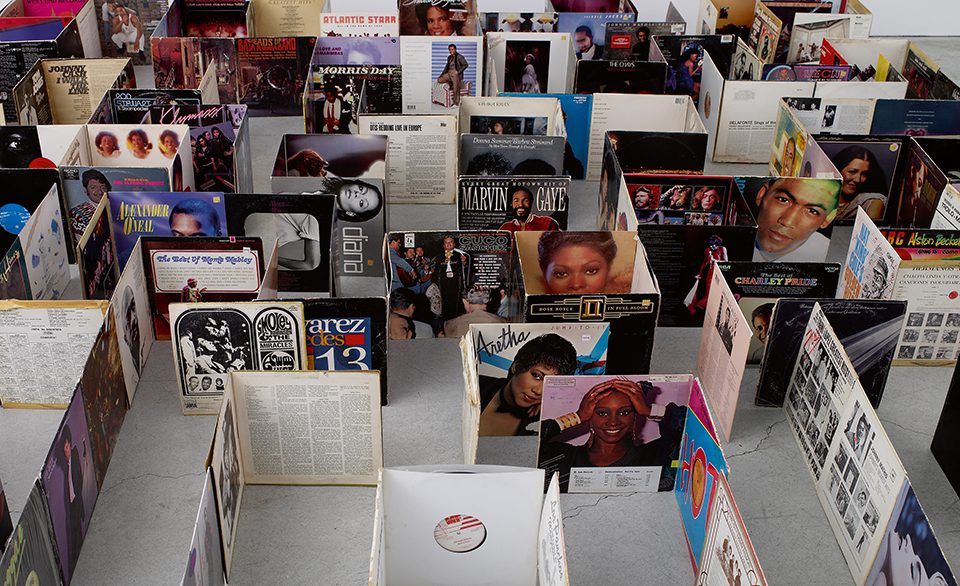

Several of the exhibiting artists, such as William Cordova, take everyday objects, and the implicit meaning in their simple form, and subvert that meaning by re-presenting it within a politicised context. Laberintos (pa’octavio paz y gaspar yanga) (2003-09), a work comprising more than 200 album covers arranged in a maze-like formation, is at first glance quite rudimentary in its appropriation of the album cover. The album covers are significant in their provenance as they were stolen from an (undisclosed) Ivy League college in the United States. We, as viewers, are informed that the museum associated with this college has refused to repatriate an equal number of Incan artefacts from Peru. Cordova, like the museum, has inflicted ownership on the objects, and by doing so highlights the tremendous problem with museum collections consisting of art and artefacts acquired through ignorance or dishonesty. Daderko says: “ Duchamp talked about his distaste for ‘retinal’ art – which he characterised as depending ‘almost exclusively upon the sensitivity of the retina without any auxiliary interpretation.’ This moment of interpretation is where change happens most readily and actively, by making the viewer a crucial part of the artistic equation.” The viewer is asked by some of the exhibiting artists to question the reality that they are presented with as the eye quite easily deceives. Jamie Isenstein’s Straw Fire (with elbow) (2011) questions the authenticity of the readymade by casting a plastic bendable drinking straw in porcelain, fitting it with a wick, and placing it within a glass bottle filled with lamp oil. The straw becomes a candle, though its outward appearance is that of a straw within a bottle: reality is skewed and the viewer must separate the performative action of the straw from its original function. Patrick Killoran’s work operates on a similar course, emphasising objects of consumer society through their reconfiguration. Daderko states: “Killoran re-frames the way we encounter objects and experiences that are initially familiar and modifies them to create a space of discovery.” Glass Outhouse (2002), a two-way mirror portable toilet, is a functional object but a disconcerting one – the patron can see everything that is going on outside whilst they are involved in what is, for most, a very private act. Killoran turns experiences inside out, thereby exposing the cultural and social conventions and mores that underpin them.

Duchamp presented the idea of the “reciprocal readymade”; the antithesis of the “readymade” as it is known today – that is an art object or painting becoming an everyday object. The relationship between “art objects” and “objects” is thus incredibly fluid, and one of the reasons why mainstream audiences find it difficult to justify the often astronomical prices paid for artworks that don’t seem to have an element of craft or the artist’s hand inherent in their making. The oft-repeated adage “my kid could do that” turns into “I could do that”, as to all intents and purposes many viewers see the works as simply objects placed on a plinth within the white walls of gallery, which somehow lends them legitimacy as artworks.

However, it is, as Daderko succinctly argues, about the choice – the artist’s decision to take an object and re-contextualise it – that is the artistic value of the artwork: “A choice that’s well-made may not seem like it was ever a choice at all. Even the choice to reject aesthetics is, at the end of the day, an aesthetic choice.” Daderko expands upon this within the exhibition through his choice of artists working with more conventional means of artistic production – photography and painting. The proliferation of digital photography and social networking sites such as Instagram has meant that the image as we know it no longer has the craft-based element which it once did. Everyone is a photographer and thus images have become, in a sense, readymades: the craft and skill previously required in producing a photograph is no longer necessarily needed. Rachel Hecker, one of the exhibiting artists, utilises the photograph as her medium of choice for her Jesus series, staging photographic portraits using popular culture figures. The portraits, in which the selected figures are presented as an idealised, airbrushed mimicry of Jesus Christ, render the visual iconography of the popular and art historical canon obsolete. Each image has a narrative implicit in it, that of the Christian iconography of Jesus Christ and the account of the famous figure, and it is a narrative which necessitates the viewer’s participation in its reading. Hecker’s oeuvre has always been inclusive of various pop culture elements that necessitate the audience’s involvement as they are rearticulated with a trompe l’oeil effect that belies their cultural significance, thereby requiring intellectual engagement from the viewer.

The direct involvement of the audience with the artworks is a participatory strand that runs throughout all of the selected artists’ oeuvres. Luis Jacob is another key example of this, as his work focuses on the active engagement of the audiences with the aesthetics of his practice, whether it is through an immersive multimedia installation or intellectually engaging works such as his Album series. The series comprises hundreds of appropriated images, culled from various magazines and publications, which are then laminated to form part of an “Album”.

Each album functions as a literal image bank from which the audience can, and should, create narratives using the visual associations of each image and the images’ juxtaposition with one another. The various images are each, in their own right, readymades, which through appropriation and the audience’s engagement take on a new meaning and significance. The exhibition takes this idea even further through each artwork’s physical placement within the gallery space, as the freestanding walls will be removed so that, in Daderko’s words: “all of the works could, figuratively, be in conversation with each other. I’m excited to see what they’ll have to say. I’m sure there will be conversations happening that I didn’t expect.”

The selected artists are each acutely aware of, and exhibit in their practice, the idea that the everyday – whether an object or situation – is of paramount importance in terms of understanding and analysing the aesthetics of popular culture. The paradox is that inasmuch as the artists are criticising the products of consumer culture, they are also producing works of art which elevate those objects to a laudatory level.

Artists such as Tom Marioni, working in the 1970s, took the detritus of social situations and elevated those objects turning them into symbols of the past event. The Act of Drinking Beer with Friends is the “Highest Form of Art” (1970) comprised the empty beer bottles and rubbish from a night when he and friends stood around talking and drinking beers. Marioni was interested not just in the ability of the beer bottle to function as a readymade, but in its capacity to retain the memory of the event in its existence post-event: how the object becomes an anthropological artefact of experience. Daderko defines this relationship between the readymade and the artist as a dialogue: “The readymade, in a fundamental way, presents us with physical evidence of conceptual process… [I’m] more interested in the productive challenges that let us continue to actively re-define the form.”

The exhibition raises important questions not just about the readymade, but about the status of the image, especially with regard to technological advancements within the digital sphere, and the role of the artist’s hand within that discourse. Inherent in this discussion is the role of the artwork as a monetised item: its commoditisation both horrifies and intrigues but it is, as Daderko argues: “About communication, and artworks can communicate very economically, reaching large numbers of people with simple means.” The art market is but a method of disseminating art, and though it functions in a capitalistic way, it still serves its purpose: providing an outlet for the distribution of art to the greater masses.

Fayçal Baghriche’s Envelopments (2010), a work consisting of 28 flags rolled up so that the country of their origin is unidentifiable, is indicative of the global reach and influence of the readymade: even if we can’t see or immediately pinpoint the origin of something, whether it be a flag or a urinal, its very appropriation lends it a new meaning. This is perhaps the most enduring legacy of Duchamp’s readymades – they created a new language with which to speak. This language continues to challenge artists and audiences alike 100 years later.

It is what it is. Or is It? ran until 29 July 2012 at The Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston. The exhibition catalogue includes seminal essays from, among others, Joseph Kosuth and Lucy Lippard, and will be available this summer. Please visit www.camh.org for tickets and further information.

Niamh Coghlan