The exploration of immersive art is celebrated in Modern Art Oxford’s multimedia installations from Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller.

Canadian artists, Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, are at the forefront of artistic interactions between new and old media, audios and visuals, immersion and voyeurism, which are becoming increasingly apparent on the international art scene. Their latest exhibition at Modern Art Oxford encompasses the entire space with a retrospective of the couple’s works, including the 1995 installation Dark Pool, the poignant Opera for a Small Room, and the macabre The Killing Machine.

Solo artists in their own right, Cardiff and Miller have increasingly become a collaborative force over the years and currently all of their larger projects are a joint effort. In a joint interview Cardiff comments: “Sometimes we don’t remember who came up with the original idea when we’re both talking about something, one person will add one thing, the other will add another thing and it will become something else.” The House Of Books Has No Windows involves a retrospective of the couple’s work, whereby each installation is taken in isolation to become an all-encompassing experience for the viewer.

The exhibition’s most controversial piece, The Killing Machine, introduces a sinister vein to the proceedings as a commentary on capital punishment, which also highlights the influences of literature throughout Cardiff and Miller’s prolific career by referring to Kafka’s In the Penal Colony. For Cardiff: “There are certain writers I always go back to because I like the formal aspect, the conceptual aspect or the fictional aspect, it still gives me the tingles that I enjoy when I read a book that’s really stimulating,” while Miller clarifies their alliance with literature by stating that, “you enter an imaginary space in a book and that’s what our work aims to do in a way, we want to allow the audience to enter our imaginary space, we create more physical spaces but we still expect the audience to input a lot from their imagination. We try to leave room in the works for the audience’s imagination.”

Miller is keen to distinguish between interactive interpretations and the immersive elements of the works, because “interaction implies that you could actually change the end or do something. Dark Pool is like that. It changes as you go through it because you choose a path through the work. However, most of our work has gone towards us being more like filmmakers, in that we control every aspect and how things go together and how they are timed so they affect you emotionally. I don’t think of it as interactive, I think of it as immersive.” With the exhibition showing in its fifth venue, reactions to installations vary, “sometimes viewers come in and they suspend their disbelief and they get into the mystery of the piece and they go around and they and turn over books and they look at drawings” and so for Cardiff the reception of the works is very much attributed the inclinations of the individual. The works continue a tradition of story-telling involving the audience as an observer, “I don’t think it’s anything new, it’s just using, not the same technologies but the same techniques as a book or a film would use.”

Through their use of multiple mediums, Cardiff and Miller seek to “come up with the best physical manifestation for the idea, often that’s why we jump back and forth through different media, because the ideas call for a different use of media. I think more of our ideas are going into three dimensional sculpture.” Incorporating audio elements into the installations has proved vital for these immersive qualities, because of how sound is able, according to Cardiff, “to enter into your body in a different way to vision and you sort of can’t refuse the sound waves,” a point reiterated by Miller, “it bypasses your intellectual barriers as well, it gets right to the root of your being and you can’t stop it.” Sound is in fact completely central to one of their most recent works, The Forty Part Motet, where 40 speakers occupy a space to surround the viewer with sound in the absence of any visual stimulation.

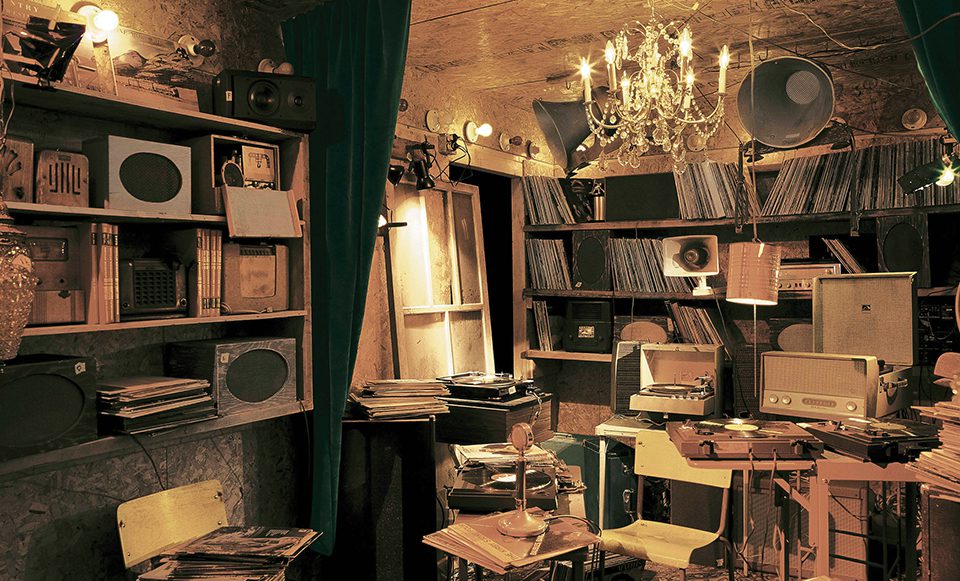

Similarly for the Opera for a Small Room installation, the audio elements contribute towards the piece’s ambience and inspire in the viewer nostalgic qualities reminiscing over a life dedicated to art. Rather than critiquing, the piece welcomes voyeurism in the study of an opera-lover’s surroundings and everyday being, in what Miller describes as “an examination of a person.” This voyeurism is again something that the artists see as subscribing to long-held cultural traditions, as Cardiff states: “I think it’s much more in the tradition of theatre, it’s much more like a stage play.”

For Cardiff, this voyeurism, the study of others and the public and private are recurring themes throughout a career of multimedia outlays. “There is something about the private and the public, in quite a few of our works, like in Paradise Institute where you sit in the theatre with other people, you feel very isolated yet at the same time you’re in an intimate situation, because you’re with 16 other people in this little box, so we do tend to use those kind of feelings of private and public.” The Paradise Institute is in fact, a particularly interesting piece of Cardiff and Miller’s, because of this uncomfortable alliance between public and private. For the viewer, there is something very strange about being in a darkened enclosed space with numerous strangers, all simultaneously reacting to the screen and inevitably reacting to one another and studying the reception among those around them.

Accompanied by a fully-illustrated, two volume publication outlining both realised and unrealised works, The House of Books Has No Windows, both a study of collaborative career and a speculation on their direction for the future, as in Cardiff’s imagination, the two are intricately linked; “we have a couple of different ways that our work has gone over the years. One of them is more staged and theatrical and then one’s more like The Forty Part Motet, and the other one’s more performing like the audio walks and the video walks. And sometimes we jump back into the genre and extend the piece then we look back at the other pieces we’ve done and we bring that into the new piece so you can follow different trails in the work.“ In these works, the past and the future are undeniably entwined and so the retrospective conversely looks towards the future, and towards Cardiff and Miller’s continued studies and collaborations.

The House of Books Has No Windows was showing at Modern Art Oxford until 18 January 2009. www.modernartoxford.org.uk and www.cardiffmiller.com.

Pauline Bache