Sama Alshaibi is an Iraqi-Palestinian multi-media artist who is currently on a Fulbright Scholarship to the Palestinian West Bank. Since 2006, she has been the Assistant Professor of photography and video art at the University of Arizona. Alshaibi recently exhibited in London at Ayyam Gallery, Art 15 and Photo London, in addition to releasing her first monograph Sama Alshaibi: Sand Rushes In in March 2015. We speak to the artist about the themes and motifs in her work, and her long-term exploration of issues around the environment and ecological refugees.

A: Your work is situated within natural environments: much of it addresses their fragility (and strength) and the threats they face. Where did your interest in this theme come from? Did it directly affect your life?

SA: In my early work, the body (my body) was the symbol of a country or people. My photographs were largely devoid of landscapes or any discernible backgrounds. I suppose that had something to do with my sense of alienation in whatever country I was living in. My childhood was one of constant migration due to our exile from Iraq during the Iraq/Iran war in the 1980s. I never related to the “place” I was in, especially urban cities. They held no memory, and changed far too often for me to get used to them. Eventually, I connected my work to the natural world, using the desert especially as a metaphor for life. I find it to be a wonderful paradox, expressing change and static energy all at once. The desert shape-shifts constantly in the drifting wind, yet it is only cycling upon itself. That is how the natural world started to come into my work. I started to see the potential of the earth to mirror and solve complicated questions that the mind couldn’t find answers to. I think there is always an example in the natural world that can teach a lesson about our complex societies and flawed human condition.

A: The artworks – photographs and videos – that you create are not mere landscapes, but are peopled, often with yourself as the protagonist. You choreograph the body into these scenes. What do you feel is the role of people in these crises? Does it represent a cause-effect relationship: people at the mercy of nature, but also causing its decline?

SA: Humans are entirely dependent on the natural world to survive. As a child of war, of exile, and even living illegally in the USA for many years, I understood the meaning of land. That essential relationship between land and life is foundational for me. My relationship to land was contentious and complicated because of my problematic national identity. Because of wars between governments, or the greed of humans who have pushed to privatize all resources, or claim land that isn’t theirs, ordinary people like my family found ourselves cut out of a system most of the world takes for granted. That may not be my reality today, but I see many in my old position – refugees, all over the world, displaced because of climate change. We are now the exterminators of the natural world, but we are the ones that will suffer for it, and already are. It is that paradox that I’m interested in playing with.

A: Is the use of the self-portrait also about identity and visibility? Where does the artist fit into this?

SA: I don’t consider my work self-portraits. I’m a character in my work. My specific identity matters little, although I use my experiences, anxieties and curiosities to inform my work. It has been many years, almost a decade, since I’ve done work that really explores my own identity. The body in my work, which is my own body, is able to perform various issues, people and concepts. I’m simply interested in the body. The fact that it is most often my body is circumstantial. I know how to use my body in performance, and to express my intention as the artist. It also allows for continuity in the work, which I find meaningful.

A: Many of your compositions focus on hands. In some, the head and face are covered but the hands are clearly visible, gesturing – sometimes upward as though in prayer, surrender, or offering; in others, interacting with natural elements in one way or another. What is the significance of this motif of hands in your work?

SA: When I started my project Negative Capable Hands (2007-2010), it was the height of the USA War in Iraq. I wanted to do a project in which it would be nearly impossible to guess the ethnicity or national identity of the protagonist. I had to eliminate the face, and use only my hands. There was a more universal implication once I did that, and it removed some of the burden of my work often being read through the context of a female Arab woman and all the stereotypes that it implied. I found it useful. I also feel that at times, the face is too personal. It is too specific, and it is hard for my audience to imagine themselves in the scene, or to understand that they complete the work by imagining what is there. To me, minus the visual of the face, the figure is more anonymous, more relatable and yet a bit mysterious. Without the face, I felt my body more easily transferred into a character.

A: I also noticed that you favour the shape of the circle: photos in a circular format, rotating patterns, symmetry and repetition. Is this merely a stylistic/aesthetic preference?

SA: No, it is about the recycling of history, repeating and recreating the same mistakes through time, through one’s life, and yet, paradoxically, the vision of the perfect form of wholeness. Complete. I am interested in these dualities. The imperfection of life, and the human desire to perfect one’s understanding. Contradiction, to me, is the most difficult and beautiful part of being human. It is what makes us human.

A: Would you say that your choice of media and composition is a way to provide an Arab / Middle Eastern aesthetic that is not commonly seen? Does the core of your practice – performance without an audience – stem from a feeling of isolation?

SA: In Silsila (2009-2014), I was actively using Islamic aesthetics in my work because of the subject matter. That is a very large and long project, so perhaps that is why it seems to be “the way” I work. However, I would say that most of my work has a more minimalist bareness to it. I like how a clean background, large fields of color or land don’t distract from the gesture or symbols in the work. Also, I’m perhaps a bit objects adverse, if that makes any sense. I’ve always had a complicated relationship with “things”. Since we lost two homelands, I didn’t inherit any heirlooms, nor was I allowed to take anything with me. I moved so much, even in my early adult life, that everything I owned basically fit into a trunk and a camera bag. I tried collecting records once, and a big storm came and flooded my entire collection. I have a distrust of the material object and being surrounded by many things disturbs me. That is probably where my aesthetic comes from. I have little need to add or subtract much from the natural world, because so much is already there to work with and to be with. I still marvel at the magic of spontaneity and simplicity. A lot more can be said with less. Performance without an audience can be a sense of isolation, but honestly, I feel more myself and complete when I’m making the work in those isolated spaces. And there is an audience – it just comes much later in the process, at the exhibition venue or at a screening. I’m always interested in what my audience considers when viewing my work. To me, art is a dialogue. My intention is only one half of that equation. I learn a lot from how people respond to my work. But the performance part that is in the landscape – that is more like my rituals, meditation, or prayer. An audience would be a distraction.

A: How did the shift in your work from themes of political refugees to ecological refugees come about?

SA: They are completely related. The lack of power and agency in the life of the refugee, whether economic, political or ecological, relates back to my own experience. And the eco-refugee will have a political dimension eventually. While I have always been very mindful of the environment (I was a vegetarian at the age of 12 because of the impact of deforestation), I started Silsila about five years ago, because of learning what was happening to the honeybee population, which was a colony collapse. The bees were dying or disappearing worldwide. It was, to me, a significant symbol of a perfect and functioning community now in duress, on the edge of extinction, because of the environment. And that might be something that we take for granted, but being threatened, facing extinction, starts a whole chain of events of loss, destruction and eventual death. So I started a number of projects that got me looking into our relationship with the land – historically and metaphorically– in order to start the conversation about these displaced bodies. To me, it is clear that when the eco-refugee becomes a category that politicians cannot ignore, it will be in unimaginable numbers. And that will only lead to more war. I can’t change my past but I hope to contribute something that makes a difference in the lives of people, for their future, our future. Our interdependence is clear to me. The era we live in now, where the privatisation of natural resources, rising greenhouse gases, genetically engineered foods and agricultural biotechnology, as well as a number of human activities that are threatening our environment, might not be on the minds of most people. But these days are limited. Some people think that the eco refugee is something only happening in the Global South, some remote islands and in the parched lands of central Africa. That is a farce. Katrina, in the USA, was a story of climate change and the eco refugee. It was also an economic story. And shamefully, it wound up as a political story. And that is in the rich country of the USA.

A: You are currently a Fulbright Scholar for the year 2014-2015 to the West Bank in Palestine. What issues/projects are you working on as a part of this?

SA: It is a little early for me to be public about what I’m doing, but I will reveal that I’m going back into an older project of mine, and bringing it to an installation level. Being in Palestine was imperative to this. Before, my research was dependent on books and the Internet and resulted in me feeling that the project wasn’t complete. I’m now able to actually to handle the materials, archives, historical objects, and make the visual and social research needed in person. Having a whole year to do that has been a gift. Besides that, I was working with the new Palestinian Museum in their education department.

A: You have exhibited globally, including most recently a solo exhibition at Ayyam Gallery in London, as well as Art15 and Photo London. You’ve also recently published a monograph, Sand Rushes In. What would you consider some of the most memorable responses to your work

SA: It is always hard to judge how people are responding initially; people are very complimentary when they come to your opening. It is only later that you really get a sense from how the world responds, and how trusted people in your life speak to you about the work. But I was blown away that so many of the magazines and newspapers were choosing our booth (Ayyam Gallery) at Photo London, especially two of my photos, as the best of Photo London and Art 15. It seemed every time I looked down at my phone, someone was tagging me with another one of these top 10 lists or “what to see”. But, as my mentor said to me a very long time ago, we should never get caught up on these things… they are basically a popularity contest or a quick snapshot. The art world can be fickle, and only over time will we know if our work had an impact. My favorite part of the exhibition component is hearing peoples’ stories in response to my work. Because the work isn’t didactic, and comes directly from stories, I think it sparks something my audience can relate to. I feel blessed when they share that with me. I actually learn a lot from their response, and it often impacts future projects.

A: Your series Silsila (literally meaning “link”), which was shown at the Maldives pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013, traces the idea of connectivity and continuity in traditions revolving around water bodies and communities living near them. How do you use this to address concerns such as “man-made” borders, identities, and divisions?

SA: Silsila uses the concept of migratory practices in a number of ways; it is an ongoing five-year project that is part travelogue, diary, documentary, and magical realism. It was inspired by the great 14th century Moroccan traveler, Ibn Battuta, (ironically called “the Marco Polo of the East”), who covered 75,000 miles after initially setting out to perform Islam’s compulsory Hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca. His meticulous notes were made over thirty years of traveling – a scientific approach to recording observations, insights and lessons all grounded in his Islamic faith that were later transcribed by a young writer, and which became al-Rihla, The Travels. al-Rihla is considered the foundation of travel-writing, and the birth of the travelogue genre. I retraced a portion of his epic journey across the Middle East and North Africa and created works in the significant deserts, oasis and bodies of water found there. I thought it was an interesting parallel, how Ibn Battuta lived like the Bedouins, their lives in continual migration, essentially erasing borders and creating community by their walking and exchanges with cultures and people outside of their own. I was also mindful of how the desert sand itself drifts across boundaries, essentially border-breaking, and as an entity, void of centers or margins. Then, there is the story of water, and our rapid approach to the end of fresh water. Set in a post-colonial context, Silsila advances pressing ecological and environmental challenges with global ramifications, while aesthetically and historically alluding to the geographic allure of the MENA region both rich and barren in natural resources and antiquity. By capturing my journey and performances in the significant deserts and endangered water sources/oases of the landscape from the Islamic world, and visually referencing the spaces documented in al-Rihla, I hoped to unearth a historical story of continuity and community. Silsila is a negotiation of the paradox inherent in the genre of the travelogue, and the body in the MENA region. I embrace the genre and cultivate a resistance – in myself, and in my audiences – that aims to trouble prevailing representations of our bodies, culture and spaces.

Find out more about www.samaalshaibi.com

Kriti Bajaj

Credits

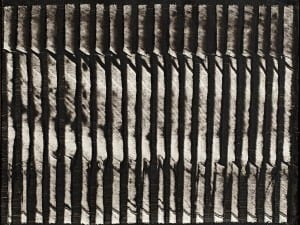

1. Mã Lam Tabkī, 2014, C-print, 60 x 90 cm, Edition of 5, Sama Alshaibi.