Fergus Jordan’s photography explores the conflict between darkness, night and artificial light. He also takes time to examine the city in photography and the status of post-conflict societies. He is an independent researcher based in Belfast and completed his PhD in Photography at the Research Centre of Art, Design and the Built Environment, University of Ulster (2012). His stark collection of images, Garden Estate, shot in Ballymena, Ireland, is currently available at The Velvet Cell. Aesthetica speaks to Jordan about his approach to this unique project and his future plans.

A: Do you remember the first photograph you shot?

FJ: I have a really bad memory and taking photographs is something I have always done. Over the years I have made a progressive shift, photographing for enjoyment to working as a commercial photographer and now considering photography as and art and research practice. I remember the first night-time photograph I took, it was in Dunclug the area that is the focus of Garden Estate. I was 16 (1998) and I just bought my first SLR film camera. I was wandering around the estate with my friend Vinny, it was snowing and everything was bleached in sodium orange. I took a photograph with the flash as an experiment, I didn’t really know what I was doing but I think it was this photograph that formed the basis of my interest in night and photography.

A: Please can you explain the idea behind Garden Estate?

FJ: The series is a reflection on the legacy of the north of Ireland’s first heroin epidemic, which devastated a 1970’s council estate on the edge of Ballymena called Dunclug during the 1990s. Up until this point class-A drugs such as heroin were something that remained locked out of the north due to the high security presence of the British army and physical community divisions. As the conflict toned down the market opened up for drug dealers to sell. Dunclug was a mixed housing estate where Catholics and Protestants lived side by side at almost a 50/50 ratio – there was no real paramilitary presence to speak of. I think it was this political neutrality that left the space so vulnerable, as it was one of the only council estates in the North where drug dealers could openly sell without any paramilitary intimidation or control. This led to an influx of dealers and by 1999 the area had several hundred active heroin users having a massive impact on this small council estate.

A: The images in Garden Estate seem to be taken objectively from an outsiders perspective – was that something you were trying to achieve?

FJ: I grew up in the estate, its my home I know the place like the back of my hand. I dislike the place but I am intimately connected to it. I have not lived their for 12 years so I was in a unique position to examine Dunclug as a result of my inner / outer relationship to the estate. I explore this idea with work such as Dunclug Night I and Dunclug Night II. I understand the social mechanisms of the estate and using this knowledge I was able to develop working methods to explore the complexity of the space. Having not lived in Dunclug for 12 years has given me the space to step away from the estate and look at it form the perspective of an outsider also. One of the most interesting things that has emerged from the process of exhibiting, talking and publishing the work is the discussion around insider / outsider perspectives and the way in which we think about public spaces and communities. Making work about a place like Dunclug is complex, I have come to the conclusion that the study cannot benefit from labeling or ring fencing. Certainly my position as a resident and returning artist reveals some of the contradictions of thinking about social exclusion/ inclusion or inner / outer perspectives of society.

A: What was it that drew you to this particular subject?

FJ: It was my interest in the radburn planning principle (The Garden Estate concept). Dunclug is one of many estates around the world based loosely on the radburn. The basic principal of the radburn model was to distance roads and cars from pedestrian pathways. Typically, this involved the creation of cul-de-sacs and parking servicing the rear of houses, with the front of the housing opening on to communal gardens and pathways envisioned to help stimulate community relations. I photographed the labyrinth of footpaths and rat runs, dead ends and cul-de-sacs exploring the complexity of the garden estate and the ways in which it aided drug dealers in the estate. I made a concerted attempt to avoid photographing the visible ghettoistion of the estate, instead focusing on the large empty voids where high-rise flats and housing stock once stood. These seemingly empty spaces speak volumes about the short history of the site. These nondescript areas intrigued me, houses sitting in isolation, hills supporting surveillance, poorly lit footpaths and the sinister nature of the shared garden spaces. The empty dark voids and complex network of footpaths became the focus of the study, amplifying the invisibly and social isolation of this community.

A: What do you have planned for the future?

FJ: I am extending my interest into the conception of the radburn planning principle, working arcoss Ireland and the U.K. In the forthcoming months I will be photographing in Glasgow, London and Nottingham Belfast and Dublin. Later on this year I will be visiting Detroit and St Louis on the development of another project keep an eye on my website for details and new work.

For more information on Jordan visit www.fergusjordan.com. To pick up a copy of his Garden Estate visit www.thevelvetcell.com.

Credits

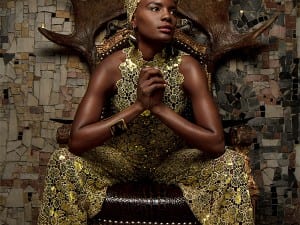

1. Garden Estate, Fergus Jordan, courtesy of the artist and The Velvet Cell.