The artist who needs no introduction takes over London with a massive retrospective at Tate Modern and new works at the Timothy Taylor Gallery.

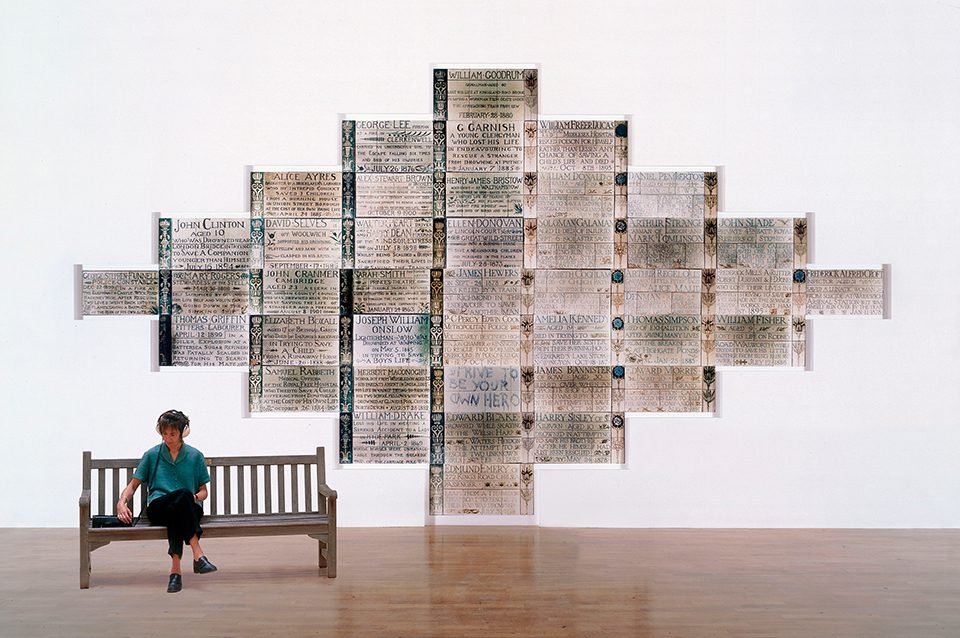

Since Susan Hiller (b. 1940) arrived in London in the late 1960s at a time when Minimalist and hard-line conceptual art was at its height, she has been making groundbreaking conceptual and installation art. Much of her work has been pioneering: in her work Monument (1980-1981) she used sound and images in an installation in a way which created the intimate and private in a public space and hadn’t been done before. Hiller’s work encompasses a startling range of techniques, materials and forms, including sculpture, sound, video, installations and projections. This accumulation of diverse work is now the subject of a major survey at Tate Britain that runs until mid-May. It’s the largest collection of Susan Hiller’s work yet shown. With its roots in second-generation conceptualism, Hiller’s practice was daring and free-spirited enough to expand the lexicon of conceptual art by applying it to subject matter that was humorous, approachable and founded in our everyday experiences of consciousness and perception. It made many of her early installations controversial with her peers, but by the same token it has been a decidedly influential aspect of Hiller’s work for younger artists.

The collective nature of many of Hiller’s works, where selections of everyday artefacts are reframed to throw fresh perspective on our attitudes, mean that many of Hiller’s works form long, decade-spanning series that pointedly remain forever open-ended. A concurrent exhibition of new and recent work at Timothy Taylor Gallery, defiantly entitled An Ongoing Investigation reminds us that Hiller is an artist still very much engaged in her projects, collections and series, some of which have been accumulating since the very start of her career.

Much of Hiller’s art is characterised by an engagement with cultural artefacts. Her seminal piece Dedicated to the Unknown Artists (1976) is based around a collection of hundreds of vintage and contemporary postcards she made between the years 1972 and 1976. It’s one of the earliest of Hiller’s works on display at Tate Britain. All the cards depict rough seas around the coastline of the British Isles. The dramatic, unruly seascapes are presented in contrasting neat and orderly framed rows, making a playful comment on the British public’s enduring fascination with its perceived inclemency. A meticulously compiled catalogue, including dates, details of the sender’s message if any and credits of as many of the photographers as Hiller could discover the names of, accompanies the piece, alongside a map detailing the locations of the postcard photographs. The title refers to the unheralded photographic artists, as well as the skills and artistry of the completely anonymous workers in the postcard-tinting industry. The collection reveals the dramatic variations of colour tinting in the postcards, a process that required considerable ingenuity, since each image was tinted individually.

Hiller initially trained as an anthropologist, and Dedicated to the Unknown Artists displays an anthropologist’s interest in collective psyche and imagination. In this work Hiller unifies the two meanings of the word “collective”, meaning both a commonality and an accumulative tendency. Her piece subtly interrogates the British tendency to exaggeratedly bemoan our climactic conditions, which is in fact one of the most moderate. A number of themes emerge in the collection, from a belief in naval supremacy, to the sense of Britain’s embattled isolation, aloof from the disorderly and riotous outside world. By taking the hackneyed images of seaside postcards and compiling them in an extensive collection, Hiller reveals and illuminates aspects of our collective imagination.

It’s an approach she has returned to throughout her career. Indeed, Hiller has continued collecting the postcards, and new work on show at the Timothy Taylor gallery includes some of her latest work in this series, entitled Rough Seas. Curator, Emma Dexter, explains the role of everyday, underappreciated artefacts in Hiller’s practice as “the taking of things that are so familiar that you haven’t analysed their political nature or how they work sociologically. Through the re-presentation of something familiar, you can see it in a different light.” The sound installation Witness (2000), involves small microphones hung from the ceiling, through which eyewitness accounts of UFO encounters are played in a number of different languages. In spite of the humorously evocative positioning of the microphones as unidentified dangling objects in their own right, the overall effect of the piece is neither mocking nor straightforwardly ironic. This is something Hiller has stressed in interviews about the work, making the point that the phenomenon of UFO sightings is part of our shared consciousness. “All these things are collectively produced and that’s what interests me about it.” The accounts are narrated with heartfelt conviction, and the sheer number and breadth of accounts is compelling. There are hundreds of encounters from many different countries. Witness tests the visitor’s belief-threshold, inviting you to consider the phenomenon for what it is, a widely held and enthralling part of our shared imagination and an adapted, contemporary incarnation of the will to believe in visionary experience.

Unusually for a conceptual artist working in the 1970s and 1980s, the irrational, subconscious, untamed parts of the human psyche are subjects that Hiller’s artwork frequently incorporates. The result is what Dexter calls a “productive tension” between her rigorous investigative conceptualism and her enthusiastic engagement with bizarre phenomena and dream-states. One manifestation of these separate impulses is Hiller’s interest in automatic writing, the free-associational writing technique adopted by the Surrealists among others to supposedly write from the subconscious mind, without the strictures and discipline of consciousness. Her early automatic experiments were exhibited as the artwork Sisters of Menon (1972). An arrangement of L-shaped frames featuring her automatic drawings, indecipherable hieroglyphs and automatic writing are wall-mounted alongside printed interpretive translations. It’s a striking work, not least because the translations are so inadequate at expressing the mystery and enchantment of the wordless symbols and drawings, which point to buried meaning-systems under the surface of our subconscious minds. Automatic writing is also utilised in her work Midnight, Baker Street (1983) in which she overlays photobooth portraits of herself with a dense layer of automatic writing.

More recently, automatic writing has emerged in Hiller’s work in her Homage to Gertrude Stein (2010), which is on display as part of the exhibition An Ongoing Investigation at the Timothy Taylor Gallery. An antique writing desk takes on literary significance, as it seems to stand in for Gertrude Stein’s desk. A number of books and textbooks on the subject of automatic writing are pointedly shelved just below the surface of the desk, as though the desk-top were a metaphor for the writer’s mind. This work perhaps as well as any other seems to articulate the tension in Hiller’s work between a commitment to research-based work and an exploration of spontaneous, automatic techniques.

The writing of experimental automatic text-based pieces is one facet of Hiller’s considerable body of language-based art. Another strain is the cataloguing and collecting of languages, to reveal their inherent strangeness. Her work Enquiries / Inquiries consists of simultaneously projected slides of pages from a British Encyclopaedia and an American one. The piece not only articulates Hiller’s personal relocation and adjustment from the United States to London, but the disparity between the two books, both purportedly written in the same language, English. More than this, the piece reveals neither encyclopaedia to be quite encyclopaedic, both equally filled with quirks and curiosities. By presenting this work in side-by-side slides, Hiller playfully reveals the bizarre in even the most authoritative of source-texts.

Hiller’s career to date has been marked by her pioneering use of up-to-the-minute technologies, a feature of her work that Ann Gallagher, Curator of the exhibition at Tate Britain has attempted to emphasise: “She has always been at the forefront in terms of new technological advances, combining media or using new innovations, such as the internet, as forms of basic cultural material.” Belshazzar’s Feast / the Writing on the Wall (1984) combines an installation of a living room environment with a background sound installation, and a television screen playing moving images of flames. The piece takes its inspiration from reports in the popular press of hallucinated visions on TV screens after end of broadcast. The living room environment is familiar and humdrum, while the lapping flames and carefully lit installation encourage the viewer to see images in the shadows and the flickers of the screen. Meanwhile, a disconcerting soundtrack plays hushed fragments from the newspaper reports, the artist’s own voice performing improvised singing and her young son narrating from his memory the biblical story of Belshazzar, in which a hand writes a mysterious, coded message of doom on the wall that can only be interpreted with the use of free translation and imaginative interpretation. Belshazzar’s Feast / the Writing on the Wall is a complex, multi-media installation that references Marshall McLuhan’s theory of the TV as replacing the hearth as the focal point of the living-environment, feeding our imagination as flickering flames once did. It operates as a critique of the materials it employs.

Similarly, when Hiller made Dream Screens (1996), a very early interactive web-based artwork in which the viewer clicks on the screen to change its colour while a woman’s voice discusses the role of dreams in modernist art, simultaneously overlapping with a woman’s voice discussing the theory of colour. The rationality of the two narratives merge and blend with a background, tapping electronic sound, altering each other into a hypnotic sequence of sounds. The electronic sound is Morse code for “I am dreaming. I am dreaming.” The viewer can choose the pace of colour-alternation by clicking their mouse regularly or irregularly. The piece explores our reactions to colour, sound, repetition and fragmentary narratives. Overwhelmed with stimuli, the participant can only focus on certain aspects. Dream Screens is a remarkably foresighted diagnostic of the internet’s fragmentary and overloaded nebulae of information.

Throughout her career, Hiller has made use of long-stretching, open-ended series of works. For example, she has consistently made series in homage to artists who have influenced and inspired her. The artists include Marcel Duchamp, Marcel Broodthaers, Yves Klein and Gertrude Stein. In the case of Joseph Beuys these works span her whole career to date, having been begun in 1969, and continued until 2009. In recognition of the unfinished, ongoing, accumulative character of Hiller’s work, the Timothy Taylor Gallery show is being held concurrent to the Tate Britain exhibition and focuses on her recent work. The most recent of the Homage to Joseph Beuys (1969 – 2009) makes use of Victorian glass vials, which Hiller finds in informal archaeological digs on the banks of the Thames. These vials are used as vessels for holy water, which Hiller collects by going on pilgrimages to holy springs and sites around the world. This is another piece where Hiller’s collector’s mentality is at the core of the piece. The piece investigates how objects are imbued with significance and sacramental meaning. The Homages demonstrate another strong impulse in Hiller’s work, a transparency about the collaborators and influences on her art, the same impulse behind Dedicated to the Unknown Artists (1972 – 1976 and now ongoing). Most of the Homages are accompanied by refreshingly frank commentaries by the artist acknowledging her debts to their work. This aspect of Hiller’s work is particularly evident in her Homage to Yves Klein (2008), which features a collection of photographs that people have made of themselves supposedly levitating. The photographs are compelling in their appearance of defying gravity. The work refers to Yves Klein’s famously faked photograph of himself “leaping into the void.” Hiller describes her interest in these photographs: “They are fascinating and I am not ironic about that. I don’t think these people think they levitated and I don’t think they produce these photographs to trick other people. They’re doing it because it’s a kind of aspiration. It’s a desire.”

These images seem to be a useful touchstone for Hiller’s artistic investigations into our known and unknown consciousness, which is at the root of the tension in her work between order and chaos. In the dramatically diverse and wide range of forms adopted in Hiller’s artistic practice over the last 40 years, there emerges a persistent and inventively tenacious attempt to illuminate the workings and implications of the imagination in collective consciousness, consistently on the tight-rope and threshold between fantasy and believability.

Susan Hiller at Tate Britain ran until 15 May 2011. www.tate.org.uk and Susan Hiller: An Ongoing Investigation at the Timothy Taylor Gallery ran until 5 March 2011. www.timothytaylorgallery.com.

Colin Herd