A rediscovery of the feminist artist Penelope Slinger presents a timely reappraisal of her work for the first time in nearly 40 years.

The art of Penelope Slinger has been hitherto neglected in the canons of contemporary art history; like many female artists working during the 1970s who defy categorisation, her work has become a sidenote within the wider historical text. This was often the case across the board: a statement released in 1971 by the Los Angeles Council of Woman Artists in response to the Art & Technology exhibition staged at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art at the time pointed out that, of the works exhibited at the Museum between 1961 and 1971, only 4% had been by women. This staggering statistic was made public in response to the fact that the Art & Technology exhibition, which had provoked the statement, contained no female exhibiting artists. The situation has started to change over the past few decades with the establishment of several centres and institutions focused solely on Feminist Art (e.g. the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art), and female artists of the period being the focus of high-profile solo exhibitions. One must be wary of pigeonholing Slinger as a feminist artist, though, as her work is about the feminine and the process of, as she so eloquently states, “female liberation and empowerment, a claiming of one’s own sexual being and one’s own sense of self and self-image.” Slinger’s photo-collages, which will be the focus of her second upcoming exhibition at Riflemaker, articulate visually the liberation of the female form using surrealist explorations of the subconscious. The exhibition, entitled Hear What I Say, will re-examine her work publicly for the first time in almost 40 years.

Slinger studied in London, completing a degree in Art and Design at Chelsea College of Art in 1969, and remained in the UK until 1979 when she departed for the West Indies. Her time at the college cemented the trajectory which she wished to pursue in her work: “The specific intention that, as an artist and as a woman, I would be my own muse. I would put myself in both places at once, as subject and object, the perceiver and the perceived.” Slinger’s work of the 1970s did precisely this, using her own naked body (and others) as the basis from which to explore various ideas related to desire, dreams, female liberation, sex, memory and surrealism. Unlike other female artists of the period, such as Eleanor Antin (b. 1935), who focused on the body as a literal physical site, as in a work such as Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (1972), in which she photographed the daily change of her body through dieting, Slinger focused on the feminine energy that she saw manifested through the physical form. Her work exists within a timeframe defined by revolt, apparent on various levels, but specifically in relation to her work, a revolt against the institutional patriarchy of the art world. The gaze, as an act of male ownership of the female form, became the focal point of much discourse, especially after the 1975 publication of Laura Mulvey’s seminal text Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Mulvey argued that desire “allows the possibility of transcending the instinctual and the imaginary”; this relationship between desire and pleasure and its visual articulation became a major focus for many artists at the time, including Slinger, who used surrealism as a means of investigating that relationship.

Her first exhibition upon leaving college, Young and Fantastic, at the Institute of Contemporary Art, London, showcased her ability to use the medium of collage and montage in order to delve into her own psyche, and her work progressively focused in on the female collective psyche as a result: “I worked across the board in many different media – painting, photography, sculpture and assemblage, life-casting, printmaking, bookbinding, film, theatre and props, weaving all together in a collage of multi-faceted feminine creativity.” The art-media technique of the “collage” and the “assemblage” had by this time been adopted into mainstream visual culture, specifically after the 1961 William C. Seitz curated exhibition The Art of Assemblage. It is perhaps quite fitting that one of the early collages, or the piece considered to be the forerunner of the technique, is entitled Still-Life with Chair Caning (Pablo Picasso, 1912), as the fragmented quality of collage lends itself to the creation of dream-like images through the juxtaposition of various images and media. It is the collage work of Hannah Höch (1889-1978), chiefly her works from the 1950s and 1960s, and the surrealist-derived imagery of Dorothea Behrens, that could recognisably be identified as the female collage-artist predecessors to Slinger. Slinger has become an influence on several contemporary female artists, the British artist Linder Sterling (b. 1954) being the most relevant (who was included in the 2009 Tate St. Ives exhibitionThe Dark Monarch, Magic and Modernity in British Art along with Slinger), as well as Francesca Woodman. For Slinger, whose more recent work involves digital collage, it is these influences, and exposure to others’ work, which create and invite a myriad of new possibilities: “I am grateful to and appreciative of those brave explorers who opened up cracks for the light to come through, and I’ve always seen myself as an opener of doors.”

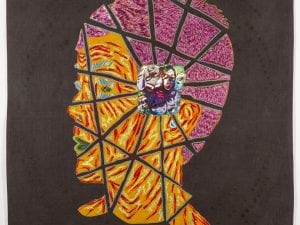

Slinger’s participation in Angels of Anarchy, a major exhibition curated by Dr Patricia Allmer at the Manchester Art Gallery in 2009/2010 that focused on women artists within the surrealist art movement, has helped to bring additional, much needed attention to her oeuvre. The exhibition, which centred around five major themes (Portrait/Self-Portrait, Landscape, Interior, Still Life, and Fantasy), highlighted surrealism’s ability to transform an individual’s imagination, desires and dreams, into concrete visual form, and in particular the way in which this form had been utilised by a variety of female artists since the 1920s. Slinger’s inclusion is therefore not surprising. Kate Kellaway stated, in a 2009 Guardian review of the exhibition, that Slinger’s “grotesque and militant contribution, I Hear What You Say (1973) … carries a loud message about silence, about being forced to listen but unable to speak.” Much of her work is about this silencing, not necessarily in a vocal sense, but rather the silencing of one’s desires and dreams, and ultimately one’s femininity, in order to succeed. Slinger silences nothing; she controls her own sexuality and success, a fact that is evident in a work such as Abreast of the Situation (1973), a photographic collage which depicts a naked breast contained within a wide open mouth. The mouth – the primary method of vocalising discontent or frustration for many – governs the feminine attribute of the breast – a symbol of the fecundity and quality of orality and sex.

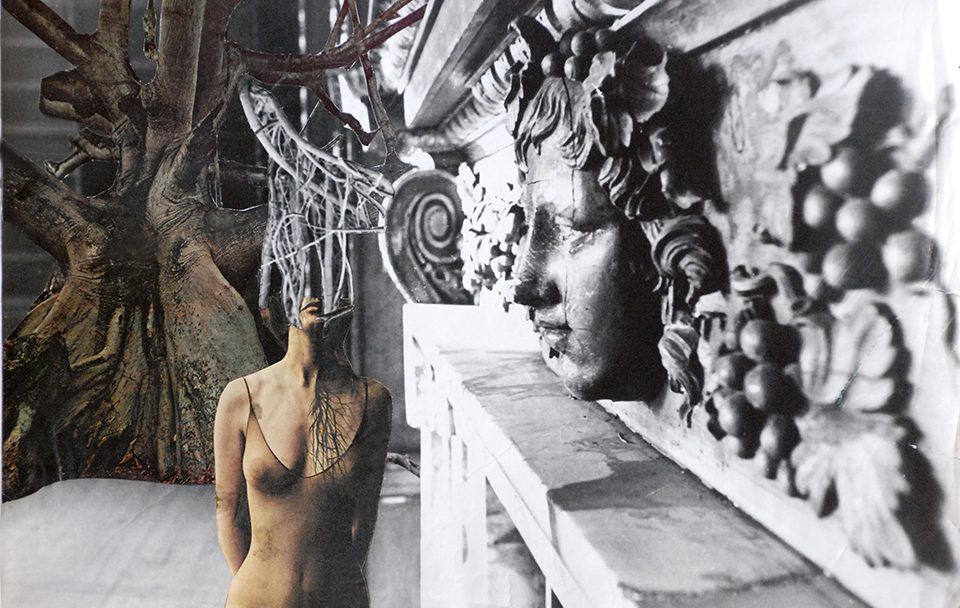

André Breton argued, in the First Manifesto of Surrealism (published Paris, 1924): “The mind of the man who dreams is fully satisfied by what happens to him. The agonising question of possibility is no longer pertinent. Kill, fly faster, love to your heart’s content.” Breton saw the moment when dream and reality meet as the formation of a new surreality, and it is this surreality which Slinger sees as integral to her work: “I feel that we need to delve into the unconscious and subconscious realms if we are ever going to hope for psychic integration, which is the cornerstone of self-liberation. I like to think that I have evolved a language that integrates the surreal landscape of dream with multidimensional visions of realisation.” Reverting, a photographic collage from the series An Exorcism, encapsulates this statement: a woman stands in a diaphanous vest, her face fading into an anterior tree branch with her body acting as a canvas for the shadows of another. The woman is framed on the right and dominated by a stone fireplace with a carved relief Bacchanalian cherub face peering out. The face of the cherub seems to stare at the female figure as well as being the replacement for the faceless woman; classical antiquity quite literally in a face off with the feminine form? This battle against Western patriarchy and outmoded historical representations of the female form occurs again and again in her work in The Exorcism, which is staged in an abandoned mansion, utilising the physical edifice of the house as way of negotiating this: “I felt the house had the feeling of ‘within my father’s house are many mansions’, a perfect glyph to represent the male patriarchy … it is the man who has the key, and the brick wall behind the door he guards represents female intuition and imagination being blocked off.” For Slinger the empty rooms of the mansion provide both an escape, in terms of the inherent possibilities of each room to act as a stage for a drama, and a channel, as each room has a doorway for the narrative to exit through and continue. The idea of the house as an architectural realisation of our dreams and memories remains a constant theme in her work, and echoes Gaston Bachelard’s 1958 book The Poetics of Space, which used the house as a starting point from which to discuss the structure of our thoughts, memories and desires. Dr Allmer states that architectural spaces, especially interiors, were and have been redefined by female surrealist artists “as the spaces inside the artist’s head – spaces of memory, dream, desire, and, above all, of freedom of imagination and expression.”

In her photo-collage series, Slinger focuses not only on the house, but also on the surrounding landscape, and chooses the motif of the flower, with its inherent feminine connotation, as a visual focal point. In Resurrection, a photographic collage on card, a female nude lies within an empty bathtub in a deserted room, colourful flower blooms laid out around her, framing her in an exquisite blanket of colour. The image is reminiscent of JE Millais’ painting of Ophelia (1851-1852), a tragic and poignant image depicting the drowning death of this character from Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Millais’ painting was a romanticised version of the reality of death whereas Slinger’s work subverts his version, quite literally turning it upside down. She depicts the female form as an earthly apparition: the body does not appear rigid with rigor-mortis but rather seems to float above the bath, defying the certain future of a death by drowning, buoyed by the flowers which enclose her. Slinger returns again to the flower motif with Sigh of the Rose (1977), an image devoid of colour save for the disparate bunches of roses scattered around the derelict mansion grounds. The one flower which is devoid of colour is the one which the female nude gently holds aloft in her hand, nose down, breathing in the smell. The title is apt as the breath (the sigh) of the female has extinguished the colour, and hence the life, of the rose. Flowers have been used throughout art history as a memento mori, but to whose death does Slinger allude, if at all? Her interest in life-energy and ghosts is integral to these works as she states that she “seeks to bring the skeletons in the cupboards to light so as to identify which belong to the essential self and which are inherited from the projections of others and the collective psyche.”

It is easy to revert back to the flower motif when discussing the erotic elements of her work as when flowers bloom, their closed buds open up to reveal an inner beauty, an almost vulva-like form, which has been referenced by more traditional female artists such as Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986). O’Keeffe’s large-scale intimate paintings of flowers have an innate eroticism about them, whether intentional or not, as it is an element of nature that is difficult to avoid. Slinger embraces that element: “The sensuality of the inner world at the heart of the flower has always been one of my personal favourites.” Slinger’s more recent works, in particular those produced after her return to America in 1990, reflect her avid interest in the erotic as tied to beauty and wisdom. She cites her discovery of Tantric Art as a seminal moment in her oeuvre as it allowed her to expand her own visual and artistic vocabulary so that she no longer struggles with liberating her own femininity as she is free: “The latest work is an expression of the liberated feminine and her multidimensional, transcultural wisdom and potential.” This work, a cycle of 64 images, is based on the 64 Yogini Temples of Tantric India, which are intimately tied to yoga, sexual mastery, deep insight, and steeped in history (the culture of yoginis dating back to 8th century AD). It is evident that Slinger’s work is anything but cyclical; instead she builds upon her knowledge, and thus her practice, creating a wider oeuvre that is still ultimately rooted in surrealism and its defiance of constraints, whether they be cultural, personal or sexual.

Hear What I Say ran from 12 September through to 30 October at Riflemaker, London. Visit their website www.riflemaker.org for further information.

Niamh Coghlan