South London Gallery has given “Shelter” to New York-based artist Rashid Johnson’s first solo exhibition in London, running until 25 November. Visiting Johnson’s “salon” (created to mimic a psychotherapy practice) encourages contemplation and reflection of the definition of art objects and the meaning behind cultural experiences. Johnson’s artworks, which have been identified with the post-black art movement, meditate on the cultural phenomena that shape African-Americans as a social group. Inspired by a diverse array of visual artists, actors, musicians, writers, activists, and philosophers, including W. E. B. Du Bois, Joseph Beuys, Joseph Cornell, Parliament Funkadelic and Sun Ra, Johnson engages with questions of personal, racial, and cultural identity through his work, producing an amalgamation of historical and material references grounded in art and African-American history.

Shelter, the title of the exhibition, presents an installation that challenges the boundaries of South London Gallery’s white cube style space by creating a sense of domestication with the featured art objects. The immersive environment, in which Johnson has produced, integrates materials from familiar contexts, such as rugs, mirrors, wood flooring, and shelves, which have been appropriated within this body of work in order to propose questions of the limitations of the art object and the power it beholds. The objects are freighted with historical and socio-political context and are integrated with craftsmanship, autobiography, design, theater, and ambience, in the artist’s typical fashion. The installation with its objects of domestic connotations and the abstract, large-scale black paintings on the walls, create an opportunity for an immersive encounter that blurs the boundary between the individual and the collective experience.

Upon entering the main gallery space, it is easy to immediately note the African associations in the installation, alluded to by the chaise lounges covered in zebra-skins surrounded by Persian rugs, hanging plants, and dark, heavy paintings on the walls. However, Johnson has intended for the transformation of the space to become a place where an imagined society can access free psychotherapy as a drop-in service. The gallery encompasses a sense of calm and peacefulness with the arrangement of the chaises, the greenery, and the glass ceiling, while the purpose of the space appears to offer more than a chance to view art, but also a chance for self-reflection.

The four zebra skin-covered day beds are carefully positioned on the rugs, with three of the beds turned on their side. Such a position poses a contradiction to the bed’s original function and enhances the manipulations of aggressive gestures as suggested by paint spills and scratches in the wood. These markings mimic those in the surrounding paintings. The calm sanctuary becomes fragmented by a closer look at the details in the works that hint at the darkness of the human psyche.

References to Johnson’s interest in cosmology is depicted in the enamel and spray paint painting on canvas, Death in Outer Space, and through the two other black soap and wax pieces with titles of Cosmic Slop. The motif of black activism is communicated in the silver gelatin print, The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Kiss), though the theme of black identity and notions of African “otherness” underlies most works in the exhibition, which provides a unified result. Johnson’s paintings, made of materials such as oak flooring, black-mirrored tile, wax, and black soap (traditionally made in West Africa), are beautiful dark, textured abstractions. The tangibility of the paintings resonates with the material objects in the gallery space, including the objects on the shelving-structure piece. This piece, entitled The End of Anger, includes objects that hark back to the 1970s and are loaded with personal and social meanings. Oyster shells filled with shea butter, books, and vinyl all nod to certain aspects of Johnson’s relationship with Afrocentrism.

These objects, which are loaded with personal and historical meaning, contribute to the overall suggestion of the exhibition – that is it is a post-colonial cabinet of curiosity. The portrayal of the Western romanticized view of the “exotic” and the references to cultural “otherness” lends itself to the contradictions of the work being presented as contemporary art in a traditionally Victorian-style English building. However, Johnson’s ability to juxtapose old sources with new ideas challenges sheltered notions of these issues in a fresh and captivating way.

Shelter: a word that means an establishment that offers cover and affords protection, has become manifested in this exhibition. The title itself evokes connotations of primitive housing, domesticated living, and feelings of being protected and comfortable. Yet, Johnson seems to be expanding on the meaning of the word by proposing questions of identity. By presenting a psychotherapy salon with African associations, he has tested the idea that this type of therapy is viewed as a purely Western practice, and in doing so he has amalgamated sources and cultural experiences through his own artistic language.

Shelter, Rashid Johnson, running until 25 November, South London Gallery, 67 Peckham Road London, Greater London SE5 8UH.

Ashton Chandler

Credit

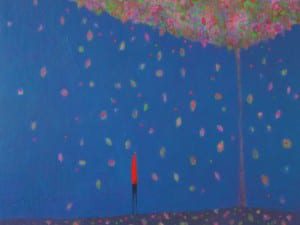

1. Rashid Johnson: Shelter at the South London Gallery, 2012. Photo: Andy Keate