Part reaffirmation, part resurrection, a new show at the Whitney surveys performance art, casting an eye over the theatrical happenings at a scarcely charted moment in art history.

Social utopianism and the belief that a collective whole could incite societal change disappeared with the shift from the 1960s to the 1970s. The crowds dispersed and movements dissolved into looser connections, creating a new world of advancing technology and an accompanying reassessment of the individual’s position in relation to wider concerns. A new show, Rituals of Rented Island: Object Theater, Loft Performance, and the New Psychodrama – Manhattan, 1970-80, opens at the Whitney Musuem of American Art, and looks at the vibrant community of artists and the experimental performance art they produced. The exhibition showcases works created in alternative spaces, lofts, storefronts and city streets that expressed the radical potential for theatre and performance as a new means of artistic expression. As Jay Sanders, Curator of Performance, says: “I see this constellation of artists representing a fascinating and unarticulated ‘secret history’ of New York art of the 1970s. While much of the radical work of the 1960s has come into view, many of the most groundbreaking aspects of this subsequent decade still remain elusive. This work speaks fundamentally to strategies being investigated by emerging artists today in the ways it addresses the commercial world, media space, persona and the body in performance.”

After the revolutions of the 1960s, there was an irresistible urge for visual artists to express themselves in new ways through the comparatively young medium of performance. Although performance art has its roots in Futurism, the 1960s really capitalised on the use of a performing body to make art. Sanders explains: “It was a special moment in SoHo, after the first generation of Fluxus and Happenings, when the innovation of the decade broke down the barriers between art and life, and started to dismantle older understandings of art. Artists in the 1970s derived from that legacy, but they had a more complicated relationship to media.” The show features many seminal artists from the era including Vito Acconci, Laurie Anderson, Mike Kelley, The Kipper Kids, Jill Kroesen, Sylvia Palacios Whitman and Michael Smith.

As a result, the Whitney exhibition is as eclectic as the artists, artworks and period it covers. Some of this next generation of performers would utilise video and sound recordings, dance and theatre techniques, as well as performance art, to create stunning multimedia sequences and tableaux triggered by or as part of the act, as in Robert Wilson’s (b. 1941) “opera” Einstein on the Beach (1976) – a project he described as a “unification of the arts.” From a subsection of 1970s work dubbed “The Theatre of Images” by New York critic Bonnie Marranca, Wilson, along with the playwright Richard Foreman (b. 1937), sought to focus on the “stage picture” – the pattern formed by multiple performers, perhaps like the corps of classical ballet, and wild stage effects. The move from narrative to aesthetics, however, makes the audience think hard about how they are going to understand this spectacle.

Einstein on the Beach (1976) is in many ways exemplar of 1970s interdisciplinary practice. Composed by Philip Glass, the opera reflects Wagner’s ethos, and comes from conversations and images that Wilson had in his mind, as well as his fascination with the effects of relativity on the contemporary world. The result was a five-hour audio-visual extravaganza, devoid of plot and only involving vague characters, which communicated its themes through scenery, choreography, props and music. The goal and idea was to create an overall impression stronger than naturalistic theatre, able to provoke a visceral response due to an avoidance of elevating actors or characters, while still creating an overall spectacle worthy of large, popular theatre. “There were a lot at artists that used themselves almost as stage hands. They were fundamentally the person making the performance, but they didn’t want the attention to focus on themselves; they wanted audiences to concentrate fully on what they were engaging with”, explains Sanders.

This naturally inverts what we usually expect from performance art, but Rituals of Rented Island: Object Theater, Loft Performance, and the New Psychodrama – Manhattan, 1970-80 seeks to make us rethink “performance art” as a genre, as artists did in the 1970s. As the title suggests, this survey of 1970s performance art from the decade incorporates several works that reference experimental theatre. This serves as a kind of challenge to a common perception of performance art as a way to execute a conceptual work in which the artist has an idea and then enacts it. The exhibition aims to shed light on a different area of performance. “Historically, ‘theatre’ has been something of a dirty word in the art world: it implies all these things that art isn’t; it suggests time and a story, and art should be a little harder and more self-sufficient with the viewer more in control of the experience”, observes Sanders, “but the work I am interested in is more about the minute by minute changes, and the way an artist deals with materials and props and their own mental state.” Robert Wilson’s theatrical performances pull the idea of conceptual performance out of shape. The work of the 1970s is personal, autobiographical, and concerned with evoking specific items or instances. Yet, an avoidance of self-centredness – despite a clear focus on the humans position – does come through. So, too, does a funny relishing of incompatibility and oddness. The work does not make sense, it implies it.

Reflecting a dystopian decade, there is no real resounding overall philosophy other than experimentation in its purest sense: an action towards discovery. Instead of providing solutions, art at the time asked questions using personal memories, autobiography, anecdote and parody to search for ways to find a place for the artists amidst institutions, occasionally finding them to be as confusing as their trajectory. Julia Heyward (b. 1949), in her performance God Heads at the Whitney in 1976, segregated the audience (“girls on the left”, “boys on the right”) and showed a film featuring clips of Mount Rushmore and decapitated dolls while walking up and down the aisle ventriloquising voices from the crowd criticising her own piece: “God talks now … No dollars for artists … No art shows …” The effect is a deeply reflexive cynicism – Heyward using her Presbyterian upbringing to question images of the government and public perception of her art, the role of family life, and state institutions, while simultaneously causing a disturbance in that it is also part of the piece. An incomprehensible time can only possibly make an incomprehensible protest, ungrammatical but not indecipherable.

Heyward clearly comes close to the preoccupations of the “Theatre of Objects”, but differs wildly in target, execution, influences and personality; she begins in performance and turns theatrical. Sanders also observes another lineage here: “There is a dramatic sense in which the person is like a vessel for media culture and subjective anecdotes, but someone like Julia Heyward or Laurie Anderson would also tell very personal and disarming stories at performances. That was really new for people. This was at the time of autobiographical art. People would tell details of everyday life, or the difficulty of living in New York, or of childhood, and weave that into a performance narrative that was structured and revealing. It would be rehearsed but the rehearsal would become part of the performance.”

Laurie Anderson’s (b. 1947) show at the Whitney, For Instances (1976), explains the original intentions of her work while displaying the final result – her autobiography goes right up to the point of performance and weighs heavily on her stage presence, as autobiography tends to do. Her work has its origins in music: a famous performance, Duets on Ice (premiered 1974), involves her playing a violin, wearing ice skates, standing on ice, and only ends when the ice melts. However, her career, like the art of the 1970s, changed along with the gentrification of SoHo towards the later part of the decade, and the increasing acceptance of avant-garde practices by the mainstream. With her six-hour-long 1984 album United States Live, featuring her surprise 1981 UK number two hit, O Superman, vignettes from American life, samples and unorthodox instrumentation, Anderson was accepted again into the mainstream of a later, more conservative political era as a kind of “Artist-Rockstar.” Satirising media artifice, and yet rapidly becoming part of it, she broke down barriers between art and the media, high and low art, by using the media itself, but also by becoming it.

The popular People Magazine eventually declared performance the art form of the 1970s – a kind of fashionable and fun “avant-garde entertainment.” In response, media-savvy artists started to play. Michael Smith (b. 1951) began in the mid-1970s performing stand-up in lower Manhattan clubs. By 1982, he exhibited Mike’s House at the Whitney, which consisted of a TV studio complete with a “living room” (the set of the TV show), dressing room and kitchenette. Smith appeared in the “living room” TV on “his show” It Starts at Home, while a tape played of him on the telephone to an obnoxious producer, talking about the possibility of having his own major TV comedy show. Smith once again eliminates the performer from his own performance while illuminating the odd paradox of the once-avant-garde, now-famous artist: how to maintain integrity, to explore new realms as an artist while making the crossover to mainstream media in that exploration, and so lose some of the protective insulation provided by the job title “artist”?

However, conversely, some of the performances in Rituals of Rented Island are almost forgotten. As Sanders points out: “We are looking at work that could be 35 years old, and it is exactly the right time to kind of “re-activate” these pieces before they’re really gone forever – many of them are already lost, because they weren’t heavily documented in the first instance.” In contrast to the growing media savviness exhibited by some artists of the period, “some of the artists didn’t even care about the durability or longevity of things they made – they just showed them to people in front of them and honestly didn’t try to make something that was marketable or would endure”, says Sanders. Artists such as Jared Bark (b. 1944) and Sylvia Palacios Whitman, the work of whom features prominently in this exhibition through photographs, are very hard to find: “They are infamous names and they travelled. The kind of hallowed figures that did this groundbreaking work without leaving a trace of it anywhere – they’re not in books, there are no photos and they’re not online, so some of those are particularly exciting because you feel like you are bringing something into the world that wasn’t visible.” A high percentage of the pieces of performance art that are well documented are due to the gallery hosting them in the first instance. “The Whitney did a multi-day festival show called Performances: Four Evenings, Four Days in 1976, and several of the artists that were in that show are actually also in mine”, says Sanders. The curators of the time were among the first to be receptive to this new style of performance.

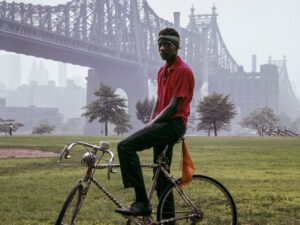

Similar attention to recording the ephemeral, unplotted aspects of 1970s art history is one of the many wonders of this exhibition. The cover photo for all of the publicity surrounding Rituals of Rented Island is credited as “Sylvia Palacios Whitman, Passing Through, 1977. Performance view, Sonnabend Gallery, New York, May 20, 1977.” A search for this performance, as if mimicking a piece of self-effacing, self-affirming 1970s work itself, only returns results referring to the current exhibition. The black and white photo of Palacios Whitman, side-on, wearing a long black skirt, white top and a pair of enormous three feet hands has, rather wonderfully, lost all context. The only remnant of this performance is a deeply biographical one of Palacios Whitman – a kind of self-solidifying photograph that only attests to that moment having been performed in all of its instructive strangeness.

Rituals of Rented Island: Object Theater, Loft Performance, and the New Psychodrama – Manhattan, 1970-80 runs at The Whitney Museum of American Art from 31 October until 2 February. www.whitney.org.

Jack Castle