Showcasing over 150 works, this major exhibition examines the diversity and complexity of art produced during the tumultuous decade of the 1980s, recognised as a transformative time for culture and society.

The 1980s are remembered for their excess and political upheaval. Reaganomics and Thatcherism had unleashed laissez-faire economic policies at the end of a truncheon. Almost all of the technology we take for granted today emerged or became affordable during the 1980s; portable audio players, microwaves, video cameras and personal computers transformed how we relate to others and ourselves. Counterculture in the form of feminism, holistic approaches to health, organic environmentalism and the gay rights movement attempted to challenge the status quo through demonstrations and provocation. Like everyone else, visual artists faced transformative influences and responded with both conservative and radical approaches.

The blockbuster exhibition This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s takes the construct of the decade to provide an overview of visual art production and by so doing “imparts the decade’s sense of political and aesthetic urgency by placing many of the decade’s competing factions in close proximity to one another.” The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago invited Helen Molesworth, Chief Curator of the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston to bring together a collection of works that might reveal the central concerns of artists practicing at that time. With a significant compendium of artworks by over 150 artists, Molesworth divided the exhibition into four distinct sections: The End is Near, Desire and Longing, Democracy and Gender Trouble. Although the exhibition has been compartmentalised into quadrants, there is an overarching theme that interconnects them: the artists’ questioning of the role of power in relation to gender, sexuality, culture and politics. Was this standpoint more at the forefront during that decade than in any other? Molesworth explains: “Art always questions…[but] because of the conservative impact of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan in rolling back the social gains of the 1960s, many artists or cultural producers of the period were processing what it means to encounter a rollback after a period of expansion around social justice or personal freedom.”

In 1980 the Equal Rights Amendment was removed from the Republican party platform and this sent out a clear message that the conditions and status of the female workforce were secondary to that of the male worker. Molesworth suggests that the feminism of the 1970s needed to be “reckoned with and worked through” to achieve any lasting impact during the following decades and for the stability of the next wave of feminism. Artists became concerned with the need to raise and communicate socio-political issues that affected them within the framework of their environment. Barbara Kruger (b. 1945) and Jenny Holzer (b. 1950) both employed text to encourage debate on experiences of chauvinism and discrimination. Artists working with conventional craft activities traditionally associated with women claimed ownership of these skills by placing them within a wider contemporary context. Annette Messager (b. 1943) and Rosemarie Trockel (b. 1952) created sculptural installations utilising female associated activities such as knitting, embroidery and sewing. However, the innocuous fabrics were juxtaposed with themes relevant to the artist such as misogyny and sexual abuse. Mike Kelley’s practice subverted, experimented with and embraced preconceptions of textile material, questioning masculinity through gender role reversals. Contributing writer, Jordan Troeller, explains: “Kelley’s debt to feminism is apparent not only in his use of yarn and the trope of the soft plaything; it is also evident in how such objects, pathetic and abject in their phallic aspirations, mobilise an aesthetics of masculine failure.”

These retrograde attacks on liberty could also be witnessed in Britain where Thatcher’s government amended The Local Government Act in 1988 by adding a clause later known as Section 28. This new law prohibited the teaching and promotion of homosexuality in schools and colleges. Instead of censoring the issue, the clause created a huge backlash of protests against its bigotry and raised greater awareness of the inequalities being experienced. The right for homosexual men and women to be acknowledged as equal to and enjoy the same liberties as heterosexuals became a major determining force in the 1980s. Artists such Deborah Bright and Isaac Julien re-evaluated gay personae and social taboos. Bright’s Dream Girls, 1989-90, recasts the artist in stills from iconic Hollywood films. By placing herself within this context she undermines the heterosexual “norms” of studio film production constrained by the self-imposed Hays Code.

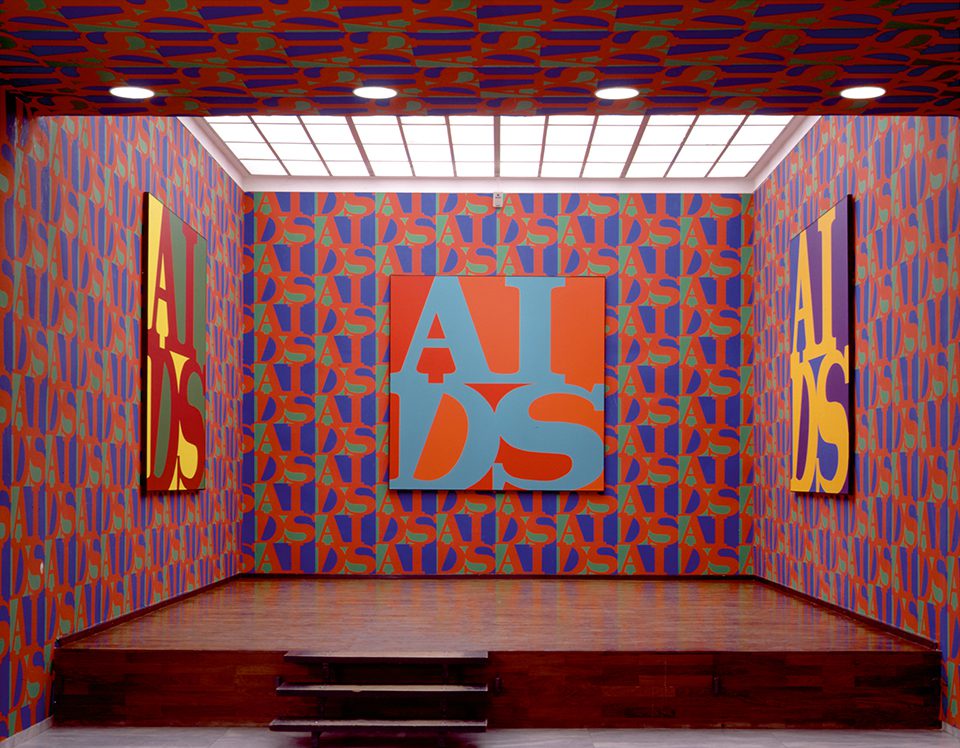

This struggle to be recognised as “valid” within wider society took on greater impetus with the emergence of AIDS. Quickly identified as a “gay disease” by conservative voices on both sides of the Atlantic, the American and British governments were unwilling to publicise the dangerous consequences that this crisis presented to everyone. Proactive artists saw it as their moral responsibility to campaign and protest against the prejudice and misinformation emanating from the popular press. Artists such as the activist collectives Group Material, Gran Fury and General Idea directly confronted the AIDS issue with billboard and poster campaigns widely advertising the correct facts about the virus and dispelling the myths and inaccuracies propagated by the Republican and Conservative Governments. Molesworth argues: “In New York the artists and cultural practitioners involved in ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) brought all their theoretical and aesthetic acumen to bear on the group’s activities, changing the look and feel of street protest as a result.” This appropriation of the vernacular of mass media informs the approach of many of the artists represented, as does a questioning of the authoritative nature of the communication industry.

The desire to legitimise the underground movement of gay culture ironically elevated the “rebel” to a point of acceptance, crossing over to be assimilated by the consumer market of mainstream culture in the following decade. Nan Goldin’s seminal work cataloguing the daily lives of friends and lovers entitled The Ballad of Sexual Dependency captured a raw, uncensored experience of her social network in New York. Goldin’s work had a transformative effect on the previous limitations and preconceptions of portrait/documentary photography; an effect that resonates in the work of Corinne Day, Terry Richardson and any number of Facebook photo albums. As emphasised in this exhibition, pioneering artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe, Alex Gerry and the controversial avant-garde performance artist Leigh Bowery (1961-1994) questioned and confronted the boundaries of sexual censorship in a repressive, conservative society. Johanna Burton, contributing writer to the exhibitions catalogue, profoundly contemplates Bowery’s personae: “Who, then, was this man who produced himself as cult figure by way of total self-effacement? Was he the logical conclusion of the sexually liberated post-1960s subject? Or was his hyperbolised subjectivity – at once infinitely deferred and totally malleable – a form of political resistance?” Consideration of identity formation and the questioning of the stability of a central “self” began to take on increased impetus at a time when mass media stereotypes saturated the airwaves.

Molesworth recognises that artists active at this time would have been the first generation to experience the constant streaming of images on televisions in the home, particularly consumerist images populated by “normal” middle-class, heterosexual, white people. The quest to reveal the diversity of society was an important challenge for artists, and within academia queer theory, identity politics and postcolonial studies emerged in response.

Even this questioning of identity within existing structures was superseded by a questioning of all formalised structures within the hegemony of Western culture by way of emerging, postmodern and deconstructive tendencies. Molesworth points to the influence of critics, Craig Owens and Douglas Crimp, in identifying and presenting the work of artists such as Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, Jeff Wall and Jack Goldstein; all featured in this exhibition. Both men wrote for the influential magazine, October, an art theory periodical in which American post-modernist art was intertwined with the post-structuralist theories of Jacques Lacan and Jacques Derrida. It was in this journal that Crimp famously presented his essay The End of Painting. During a 2003 Artforum panel-discussion, David Joselit said: “The death of painting opened things for the unrestrained will to power of the critic, and the unlimited freedom of interpretation that went with it. ‘The painter is dead. Long live the critic!’ pretty much encapsulates the reversal that was ushered in by poststructuralist theory.”

The works Molesworth has chosen to exemplify the debates of the time include photographs of paintings (Robert Gober), paintings of photographs (Jack Goldstien), paintings of paintings (Dotty Attie) and various non-paintings that reference painting. A lot of the vitriol of the age was directed at the dominant school of neo-expressionism painting, which seemed to restore notions of the male genius and in doing so the whole edifice of higher authority. Arthur C. Danto, speaking at the panel discussion mentioned above, puts this antithesis in a broader context: “The Death of Painting was in part an expression of resentment against the painting that was causing so much excitement in the early 1980s, neo-expressionism. But it seems evident that the target must have been, in part, the form of life in which the affluence of the Reagan years expressed itself in collecting art, in ‘getting in on the ground floor’ through acquiring paintings that were certain to appreciate in the way that Abstract Expressionist paintings had done.”

Being outside the neo-expressionist stable did not necessarily mean being ignored by the market. Although Jean-Michel Basquiat exhibited with artists considered neo-expressionist he seems to have escaped being labelled as one. Perhaps his emergence from “street artist” authenticated his practice to those who questioned the authority of careerist painters. The shift from street to gallery for artists such as Basquiat and Harring coincided with the rise of hip hop and rap as agents of cultural transformation. Sampling was an aural form of appropriation, driven by a desire to create within limited means and a celebration of the source origin – not a theoretical attack on existing centres of power. As Clare Grace points out in the exhibition catalogue: “By the power of anonymity and a rigorously non-commodifiable medium, graffiti occupies urban space subversively (and illegally), thus providing a means of public self-representation for individuals of a disempowered social class.” The fact that the market assimilated these art forms so quickly is a portent of our present situation in which all artists are part of the creative industries; even dissent can be packaged.

Molesworth ensures that the marginalised have a voice in this show by including Handsworth Songs from the Black Audio Film Collective in which the 1980s riots in Birmingham (UK) are explored through first hand interviews, press coverage and documentary footage. Chilean artist Eugenio Dittborn’s meditations on repressive state power and its use of identity as a tool of control are rooted in his country’s history under Pinochet, as are the broader explorations of inequality by fellow Chilean, Alfredo Jaar. In the same vein, Brazilian Cildo Meireles’ formal presentation of upright magicians’ wands entitled Desaparecimentos, gives testament to the many thousands of individuals who were “disappeared” by government forces in the 1970s and 1980s. Anyone who has read Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine will understand the significance of the period explored in these artist’s works.

Through This Will Have Been… Molesworth forces us to reassess the decade that most commentators treat with contempt because of its association with rampant capitalism. In the process she challenges present-day artists, curators and institutions to question more. This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s ran from 11 February – 3 June 2012 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. www.mcachicago.org.

Angela Darby