There are around 3.24 million hectares of woodland in the UK, accounting for 13.3% of total land area. In June, the risk of wildfires in England and parts of Wales was raised to “very high”. Meanwhile, an “extreme” warning covered some regions of Scotland as temperatures soared. As such, Met Office research concludes that these conditions can be considered an “emergent risk.” The tragic, devastating effects of extreme weather events are resonating across the globe, with Hurricane Lee, Storm Daniel and Typhoons Haikui and Saola making headlines in the first two weeks of September 2023. This is the backdrop against which the work of photographer and Aesthetica Art Prize alumnus Ellie Davies (b. 1976) emerges. She has been working in UK forests since 2007. In recent years, her imagery has become increasingly concerned with the pressing threats facing our ecosystems – from rising sea levels to pollution, tourism and more. Now, her new book Into the Woods charts this creative evolution.

A: Where does your passion for forests originate from?

ED: I have loved woodland since my early childhood. I grew up in the New Forest in the south of England, and we lived in a 500-year-old thatched farmhouse surrounded by old growth forest. My parents were interested in a 1970s, “back to nature”, approach to life and were both very knowledgeable about wildlife, plants and trees. Walks in the woods were filled with imparted information and stories. My mum’s family members are all artists, so in every outing she found ways to be creative and taught me to start really looking at the natural world; photography is so much about learning to look. The forest was a place of adventure and early independence, and its inherent sense of magic has never left me.

A: Trees appear in myths, legends, folklore and fantasy. Why have they have captured the human imagination?

ED: Human relationships with trees go back as long we have existed. They have provided us with food, shelter and safety but also a sense of the unknown. When we enter forests, the air cools, time seems to slow and we are transposed into a more animal state – where all our senses are heightened and we are more aware of ourselves. Woodlands can be breathtakingly beautiful, full of space and light. But, due to weather shifts, they can quickly change, becoming cramped, dark and tangled. In an instant, they might transform from somewhere comforting, safe and picturesque to lonely and sinister. Myths and legends usually carry a warning at their centre, teaching young people how to navigate the temptations and dangers of the outdoors. The forest is often used as a metaphor for growing up and the challenges and hazards we will face, as well as the different pathways we may choose in our lives. These lessons can be extrapolated to the wider world.

A: In Stars (2014-2015), you draw on images from the Hubble Telescope, interposing ancient forest landscapes with the Milky Way. What sparked this series?

ED: I moved to London in 2000 to work and study. Whilst I loved the city, I felt hugely disconnected from the wild places of my youth. I began to think about articulating this changing relationship in my photographic work. I was interested in how our interactions with the environment, particularly in the UK, are managed and mediated. The idea to overlay stars from the Hubble Telescope onto forest landscapes was a rather literal interpretation of my sense of distance from nature, something often experienced by city dwellers.

A: In 2023, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope produced the deepest and sharpest image of the universe to date. How did you react to seeing the pictures?

ED: The new images from the James Webb Space Telescope are absolutely mind blowing. JWSP detects infrared light, which has travelled to us for 13.5 billion years, allowing us to see the formation of the first stars and galaxies in the early universe. As Professor Brian Cox says, “essentially from the beginning of time”! I am fascinated by the mysterious concepts of dark matter, which governs the growth of cosmic structures, and dark energy, which accelerates the expansion of the universe. The Euclid space telescope, launched for a six-year mission in 2023, will chart the largest ever 3D map of the universe, up to a third of the sky and 10 billion light years away, to explore the evolution of the dark universe and hopefully to better understand the invisible source of this mysterious gravity. Particle physicists suggest that it may be a new particle that doesn’t interact with our light, so is invisible, but does exert gravity on the mass of our universe. I would love to work with these ideas.

A: You use layering techniques again in Chalk Streams (2023) and Seascapes (2023). Can you tell us more?

ED: It is impossible to talk about the natural world without talking about climate change. I had become interested in the chalk streams of Dorset and Hampshire, near where I live, and the increasing pressures on these important ecosystems due to the destructive human impacts of climate change. They include rising sea levels, pollution, water abstraction, farm runoff – the list goes on. David Attenborough recently described chalk streams as “one of the rarest habitats on Earth.” There are just over 200 globally, 85% of which are found in the UK. They are typically wide and shallow, their cool clear waters emerging from underground chalk aquifers to flow across flinty gravel beds, maintaining a stable temperature year-round. I had already created images on the rivers Test, Itchen, Piddle and Frome, but I wanted to find a motif I could use to highlight my message. Later that year, I went to Dancing Ledge in Dorset for a swim and the sun was shining. It shimmered on the surface of a small rock pool and I filmed it over and over again on my phone, absolutely mesmerised by the zigzagging and spiralling patterns. It was perfectly kinetic. I thought about it many times over the next few months, and decided to use it as a visual reference point to represent the sea. Chalk Streams draws attention to the relentless altering and damaging of wild places, as well as the need to protect them. The series is a call for change, and, although it reflects a sense of deep concern about the urgencies of the climate crisis, it also holds an enduring hope for the future.

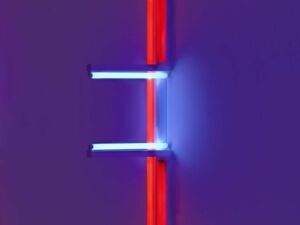

A: Fires (2018), whilst beautiful, could be seen as taking on a new meaning in 2023, as forest fires have devastated large areas of Europe and Canada. How do you see the relationship between art and climate action?

ED: We need art to process and articulate the world around us. We can feel overwhelmed with the horror and impending doom of the climate crisis. Art allows us to see the world afresh, and to find new energy and perspectives to bring to these problems. The desire to fight for ecosystems is often proportional to how intimately connected to them we feel, or how relevant they might seem to our own lives. Art, and especially photography, has the power to raise awareness. It can deliver information about environmental issues to new audiences in ways that may resonate more personally. I recently discovered the work of Thomas Jackson, a California-based artist. He is inspired by fire and uses the wind to create dreamlike images featuring coloured tulle floating over seascapes or grassland. His work is particularly resonant right now, as we are seeing more and more catastrophic fires, stoked by strong winds, raging worldwide.

A: Who are your creative influences? Are there any environmental photographers you look up to, for example, or any key artworks that have sparked your interest?

ED: I have always loved the work of British artist Andy Goldsworthy. My parents went to an early exhibition in the 1980s and brought home a monograph. They later purchased a print called Iris Leaves and Rowan Berries, a crosshatching of reeds, fastened together with thorns and floating on the surface of a pond. Some of the geometric spaces were filled with bright red rowan berries. I was absolutely struck by how Goldsworthy used found materials to create sculptures which are inherently transient and ephemeral. It encouraged me to be experimental and to think outside of painting and sculpture, which I was being taught at school. My childhood attempts at sculpture incorporated some of the classic Goldsworthy techniques – from bonding ice with my breath, to pinning leaves together with thorns. These experiences are what first made me to want to be an artist. I also loved reading about Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field (1977) as a teenager – the sheer scale and grandeur – I would love to visit it one day. Auguste Rodin and Barbara Hepworth’s sculptures had a big influence on my early artistic attempts with clay and metal. In photography, Jeff Wall’s narrative constructions, Edward Burtynsky’s ravaged landscapes and Chrystel Lebas’s meditative snowfields showed me the breadth of contemporary image-making.

Into the Woods | Crane Kalman Brighton

Worlds: Eleanor Sutherland

Image credits:

1. Ellie Davies, Fires 7, (2018). Image courtesy the artist.

2.Ellie Davies, Chalk Streams 2, (2023). Image courtesy the artist.

3. Ellie Davies, Stars 8, (2016). Image courtesy the artist.

4. Ellie Davies, Fires 9, (2018). Image courtesy the artist.

5. Ellie Davies, Stars 8, (2016). Image courtesy the artist.