It has become a rite of passage for the contemporary poet: the attempt to rewrite classical – specifically, Hellenic – literature for the modern day. Yet though the projects seem comparable, their impulses are often wildly different. In recent years, they have ranged from the translational (Heaney’s The Burial at Thebes) to the wildly unpredictable (Hughes’s Oresteia) to the strongly interpretative (Logue’s War Music). All are united, however, in their subtlety, the way in which they adapt without abusing their poetic license. In this sense, Simon Armitage is a worthy new addition to the poet-cum-classicist Hall of Fame.

The Last Days of Troy modernises without butchery. It thereby avoids making the same mistake as Don Taylor, whose translation of Antigone, staged by the National Theatre in 2012, grated for its anachronism, its admixture of idioms divided by many miles and millennia. In fact, despite its titular claim to originality (making no direct reference to its source text, Homer’s Iliad), the play-text includes some very close translation – specifically, the supplication of Achilles by Priam in Book 24, where Armitage’s aim is not to poeticise but to highlight the existing poetry of the Greek. Unusually for drama, this extends to incorporating Homer’s penchant for elaborate itemization of weaponry (the Greeks’) and gifts (Achilles’) – the delight of which, it transpires, is sweeter spoken than read.

Yet this reverence for the original perhaps extends too far, leaving Armitage slightly restricted in his characterisation. At times, the characters conform to the expected stereotypes: Jake Fairbrother’s Achilles is petulant, Tom Stuart’s Paris is mincing, David Birrell’s Agamemnon is as shouty as you might expect. The performers tended follow to the expectation of the old, rather than rising to the challenge of the new. Fairbrother’s delivery often seems to echo the awkward cadences of past translations, not always taking advantage of Armitage’s fluent prose. Poster girl Lily Cole does better as a dour, disdainful Helen, though sometimes lacks the majesty required to pull off this pivotal role with tragic élan.

However, Armitage’s innovation is introducing laughter to epic. Taking inspiration from Monty Python’s Life of Brian, Waiting for Godot’s Pozzo and Morgan Freeman’s God in Bruce Almighty, we begin with a haggard Richard Brennan clambering onstage from the Yard, opening a battered suitcase, standing atop a small pop-up platform and placing beside himself a cardboard sign that reads, simply, “ZEUS”. The comedy that buttresses the play is not merely farcical, but tarry black, its hopelessness Beckettian: “Of course I live in the past,” says Zeus, “I ruled over the cosmos once.” In a manner akin to Shakespeare’s own Troilus and Cressida, its humour stands indeterminately between light relief and bilious undercurrent.

Perhaps the greatest strength of the play’s darkly comic streak is in drawing attention to its own outdatedness. “No one could fight in this,” says Andromache (Clare Calbraith) as she arms her father-in-law Priam (Garry Cooper), “it’s a museum piece.” The gods aren’t mountain-moving deities, but short-tempered fogies spouting snarky side-line commentary. Their bathos scuppers any attempt at heroic grandeur, either on Earth or Olympus. Yet as Troy falls, the devastatingly beautiful Helen led off to resume her position as Menelaus’ chattel, we cannot help but feel that sentimental void the play sets up is perhaps too gaping, its apathy too cruel.

Rivkah Brown

The Last Days of Troy at Shakespeare’s Globe, 21 New Globe Walk, Bankside, London, SE1 9DT www.shakespearesglobe.com

Follow us on Twitter @AestheticaMag for the latest news in contemporary art and culture

Credit:

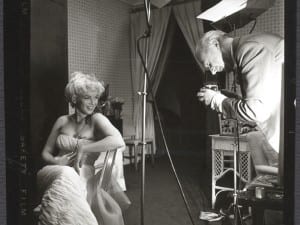

1. The Last Days of Troy at Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester. Photo © Jonathan Keenan. Courtesy of Shakepeare’s Globe