Surface and reality are integrated and juxtaposed in Sally Potter’s pared down approach to filmmaking.

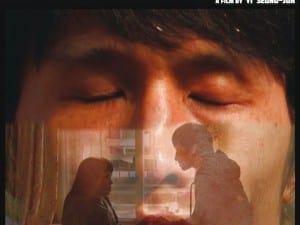

The expressive fluctuations of the human face are endless – happiness, fear, hysteria, hope, disappointment, disgust and nervousness…, Rage strips away cinematic paraphernalia to the bare minimum of the character and their emotion, the basic elements of the craft which are all too often left behind in the fight scenes, explosions and sumptuous scene-setting of today’s cinema. The technique is innovative, with groundbreaking writer-director, Sally Potter (The Gold Diggers, Orlando, The Man Who Cried) at the helm, to scratch the world beyond the surface, in a film which is itself highly stylised to Pop Art pretensions.

Rage sees a schoolboy’s project unfurl the under-layer and the confessions of the fashion industry through a series of monologues from participants in all aspects of the show. Michelangelo, the silent schoolboy lays witness not to the two killings during the week, but instead to the characters’ reactions to the action off-screen. In its focus on the human face, Potter’s film becomes devoid of setting. Each character reveals their monologue in front of a flat, bright screen. Throughout the tragic events Michelangelo becomes the confidant of the interviewees. Characters that were once caricatures are stripped bare to their own vulnerabilities and fears. A product of the new media age, Michelangelo’s work is soon posted on the Internet, and these characters, who have revealed themselves to him, are betrayed, having revealed something more than their public identity.

As the camera operator, Potter spent an intense two days with each actor and found herself assuming the role of listener, trying to identify what it was about Michelangelo that encouraged people to strip down their façade: “Clearly there’s something about this silent gaze, these wide eyes. I tried to feel that energetically, to give something for the actors to play off so that they weren’t talking into a vacuum, they were making a real relationship, with an imaginary character.”

The distinction between the public, constructed persona and the private self is something that interests Potter especially in reference to today’s media age. Considering “the anonymity of the Internet users, the invisible bloggers, the way in which the Internet allows for pseudonyms. They create a fictitious identity that allows them to alter things quite powerfully.” Even in “real” social network sites such as Facebook and MySpace, the fabrication of an identity is integral, you select which photos to display, which to tag, which songs to play, what interests to list. “It’s a total construction, everyone’s playing a part, creating their own image, the self they want to be seen.”

The cinematography is almost Warholian. After filming in front of a green screen, the background is manipulated into a series of lurid colours, starkly contrasted with the inky greys immediately after each accident. This lineage was something of which Potter was well aware: “I suddenly saw the resonance when I was putting the colours behind the characters because I was choosing to use quite flat colours, and then with the gradients that you can do on the laptop to make it slightly flatter, it did almost become like a talking silkprint.” Although the part of each character is immediately clear – the eccentric designer wears a twisted, waxed moustache, the models are heavily styled to emphasise their doll-like vulnerability (Lettuce Leaf) and their grotesque androgyny (Minx), and the writer is shrouded in cynical self-aware black – we see little of the actual subject on the world which they inhabit – fashion. “The fashion world is something that is over-exposed, you don’t need to see clothes, the clothes people wear are very precise, very minimal and you don’t really see any of the designs.”

Surprisingly, for such a character-led script, Potter hadn’t established casting preferences when the script was penned, although she describes casting as “the alchemy of filmmaking.” Varying from the very established, to new performers, the actors involved seized an opportunity to connect with their reasons for choosing their industry. “The actors could all recognise in the structure that it was going to be terrifying but also a great opportunity to be so exposed. They had nowhere to hide and had to be completely connected to the material, with the moment, with the lens.” Potter describes the work as: “Minimal in its form, but maximal in what’s possible with the human face. I wanted to try and go back to the absolute basics of what it means to look at a face unravelling in front of you, how much you can get with the most minimal means and going beyond the conventions of film language, to go back to a much simpler language of communication and allow its richness to be visible.” With no sets and on-screen “action” the film’s soundscape becomes of paramount importance, it’s our only insight into the world beyond the lens, snatches of chaos and disaster, perpetuated by the character on screen’s reactions to the events outside. The idea behind the micro-focus was in part to establish a juxtaposition between the fashion world and its subjects. Potter is focused on surface, not as a critique of society, but as an exploration of it. “If you’re dealing with people’s feelings and experience (which is intangible) in a world that is dedicated to the appearance of things and to surface, you’ve got a very interesting tension. An unveiling and unravelling of the person inside the face, inside the body, wearing the clothes, that we all are.”

Entitled Rage, we never see any rage in front of the camera. Similarly for a murder mystery, little is seen of the actual investigation beyond the almost absurd Shakespeare-citing, over-inflated detective Homer. Potter’s characters run the gamut of emotions, but essentially the rage itself is enacted off screen. Rage is about what’s not seen as much as what is; we catch furtive whispers backstage; and the fashion world behind the camera, so visible in reality, is pushed aside in the film. We see the fashion world’s hidden and suppressed elements, in spite of reality television and the “famous for being famous” mantra, this hidden nature of events has become the way of the 21st Century. Bradley White, the show’s marketing consultant comments: “You don’t die in public,” an attitude which personifies fashion and yet when wider issues are considered, fashion’s biggest nemesis is negative publicity over the size-zero debate, its stars could quite literally be dying on a very public stage. There’s an interesting contrast between the figures who are desperate to be visible, celebrity supermodel Minx, ambitious intern Dwight Angel, and those striving to maintain their very invisibility, Anita de Los Angeles personifying the legions of hidden garment workers across the developing world.

Potter’s film addresses wider issues. Despite the microcosm of her filming environment Potter realised that nothing can be taken in isolation. “Fiction is just another window on what exists, another way of putting it back together in a way that we can see it more clearly. The fashion world is an invisible setting, but that is totally implicated in, and indivisible from, the global economy, recession, developing world workers, body images, glamour, celebrity, self-image, vanity, redundancies and so on. It’s part of an indivisible global whole. The delusion in the fashion world is that somehow it’s a world apart from other things that exists in a bubble. It doesn’t, it’s just that we don’t get to see the underneath parts.”

Tying the story into reality, Potter hopes to undertake the world’s first interactive, multi-venue film premiere, incorporating live Twitter, Skype and SMS Q&A chat at multiple venues alongside the red carpet event. “It’s nice to be groundbreaking but it’s also an inherent part of the story. Michelangelo is himself recording things on a cell phone, putting it on the Internet, in ways that some of the people he’s filming don’t even understand, it’s a much more dispersed, periodic relationship with the ether and a very rapid flow of information, to echo that in the way we distribute it would seem to make complete sense. It’s a way to let go of control, so here it is, mash up my movie.”

Rage was released on an international multi-platform on 24 September 2009 (cinema / mobile / Internet / DVD).

Pauline Bache