‘I have a stag for you’ the woman heard.

‘She was astonished and delighted, she could barely speak.’

‘But he’s very thin’ the friend went on ‘he’s borderline’

‘He much does he weigh?’ was all she asked.

‘As much as a man’ he said.

Extract from Berlinde De Bruyckere. Romeu my deer 2012.

Berlinde De Bruyckere is well known for her corporeal sculptures painstakingly created in resin and painted wax and rendered uncanny in their skin-like mimicry. They hang, lean, or lie like contorted corpses, and unsettle the viewer with their disconcerting naturalism as they appear to teeter between death and a seemingly latent vitality. However the new sculpture now showing at Southwood Garden, one of the first works of the artist’s to be publicly presented outdoors, witnesses a transformation from this more directly fleshly and visceral aesthetic, towards the use of ‘heavier materials’ which, in the words of De Bruyckere, express and parallel ‘the heaviness of death’. This alternative rendering of physicality through the permanence of metal rather than the fragility of wax, explores a shift away form corporeal immediacy and its inevitable finiteness, towards a comment on an immortalising or memorialising of the body after death.

On the 4th September 2012, to celebrate the unveiling of this new work, visitors were invited to view a one-off performance by the contemporary dancer, Romeu Runa, as well as to see the temporarily installed sculpture Actaeon III (London), 2012, which was shown for the first time just for the duration of the opening. These events took place in conjunction with the launch of, Berlinde De Bruyckere. Romeu my deer, the final book in De Bruyckere’s narrative trilogy. For this brief, transitional moment viewers were able to appreciate this outdoor sculpture entitled Rodt, Januari, 2012 within the context of three complementary pieces. By virtue of their differing media and intrinsic communicative qualities, the narrative text, performance, and temporary sculpture served to cast Rodt, Januari, 2012 within a symbolic and temporal framework thus highlighting the complex strategies and processes at work in the experience of spectatorship.

The significance of narrative, whilst never directly implied within De Bruyckere’s sculptures, has often occupied an oblique or peripheral place. Berlinde De Bruyckere. Romeu my deer provides the literary counterpoint to Rodt, Januari, 2012 raising the idea of the life force as indistinguishable from that which embodies and animates both man and beast. Thus the question that the protagonist asks herself: ‘Can I kill a stag?’ takes on an almost murderous gravitas. Meanwhile, the comparison made in the introductory quote between a man and a stag, and the notion of the animal as being ‘borderline’, gestures towards a liminal space in which human and animal, as sentient beings, occupy transitional categories.

This conception of metamorphosis or shape shifting between man and beast is one which was extraordinarily encapsulated in the performance executed by Romeu Runa at the occasion of the opening. The performance begins as Romeu Runa stands naked facing a wall, a pair of painted wax antlers hanging before him. A vulnerable, strangely pathetic figure, he waits. Imperceptively at first he begins to flex and contract his muscles. A slow rotation of the head and rolling of the shoulders give one the impression of a newly birthed animal experiencing the first explorations of physicality. The extent of movement builds gradually; jerky, unsteady, the human body rendered unfamiliar in its contortions. The antlers become incorporated into the expressions of the figure. Extensions of limbs, they are rotated around the body and pressed into naked flesh both aiding and supporting the figure whilst also restraining and afflicting it. The rhythm of movement increases, metered out by stamps, snaps and snorts which issue from the subject and reverberate around the lofty, now eerily silent gallery space. The speed and intensity of expression builds as he approaches the wooden platform in the centre of the room, his ‘stage’. The pathos of spectacle is immense. As the performance climbs to a crescendo inhuman moans and cries are expelled, uncanny in their deer-like precision. There is a savage vulnerability played out in the fitting or death throws of the anguished, shuddering subject as the antlers are raised and smashed repeatedly before he collapses, exposed, spent, dead even, upon the rough wooden ground.

It’s all over in a few minutes, but as the figure lies there one has the lingering sensation of having been witness to something of the instinctual pains and passions of lived experience, innate animal impulses not particular to the human. The spectacle of human as animal leaves you slightly cold; it is as disconcerting as it is poignant.

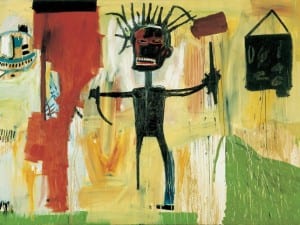

Upstairs upon a similar wooden platform to the one below, a tangle of rags, intricately painted wax antlers and drift wood comprise Actaeon III (London), 2012. It acts like a melancholic scene after the event, an echo of presence and action past. As if picked over by vultures, all that remain are the lasting ephemera of horn, wood and fabric. The flesh and body are resolutely absent.

Yet the lasting work of this show, the piece by which it will be remembered by all those who did not attend the opening, is placed outside the walls of the gallery fittingly beneath the shadow of St. James’ Church, Rodt, Januari, 2012. A prone, decapitated deer lies immortalised in lead, bronze and tin. Its granite support, set on a wooden crate, is reminiscent of the mortuary slab and butcher’s bench, but it also gestures to the wooden platforms which supported Romeu Runa and Actaeon III (London), 2012. However the enduring impression of the work, expressed by its permanence and its understated monumentality, is that of the memorial. A strange inversion of the trophy- in which the head and antlers of the slaughtered stag become a signifier of human conquering over the animal, this headless deer becomes a poignant testimony to the universality of death, and the sanctity of life both human and animal. The headless deer operates in much the same was as De Bruyckere’s faceless humanoid forms do by commenting on universal lived experience without referencing the individual or particular.

Subsequent visitors will not be able to see the work as the final act within the tripartite framework through which I viewed it. The event has definitively passed and yet the narrative remains to inform and influence its appreciation. Thus finally this piece also touches upon the significance of the memorial and narrative to mediate the past and shape the present.

Text: Hannah Foster

Berlinde De Bruyckere, 5 September until December, Hauser & Wirth Outdoor Sculpture, Southwood Garden, St James’ Church, 197 Piccadilly, London, W1J 9LL. www.hauserwirth.com

Read the full preview here: www.aestheticablog.com/blog/

Credit: Actaeon 2011 – 2012, 2012, © Berlinde de Bruyckere. Courtesy the artist and Hauser and Wirth. Photo: Mirjam Devriendt