Artists’ films, at times, can be challenging in their context, but change that context and a new experience emerges. Spring 2010 saw leading visual artists work enter UK cinemas in subversive and playful ways, to a diverse and large-scale audience.

Despite a much smaller audience than mainstream film, artists’ films are far more innovative and freely creative than anything generally seen in the cinema, evoking a range of responses from antipathy to delight. For every grainy, amateurish attempt at an avant-garde statement, engaging, moving and even exquisite artists’ films have gradually become more commonplace. A benchmark of this development came eight years ago with an exhibition of Sam Taylor-Wood’s films at the Hayward Gallery, London; no matter how unimpressive the content of her work on display may have been, it was hard not to admire its production standards, which were reassuring about the general state of artists’ filmmaking.

Her recent film about John Lennon, Nowhere Boy, marks her move from galleries to cinemas, and no doubt benefits greatly from a discernible narrative. Another widely known artist-filmmaker is Steve McQueen, whose dynamic work won him the Turner Prize in 1999. He famously went on to make Hunger (2008), his hugely provocative film about Bobby Sands.

Taylor-Wood and McQueen are perhaps the two most high-profile recent British artists known for their film work to cross the great divide into mainstream cinema, that Holy Grail of cultural attainment. Like pop stars yearning for celluloid immortality, it appears that cinema continues to draw hopeful, successful creatives striving for the ultimate vanity project. Of course, Kutlug Ataman did the reverse and went from making cinema features to artists’ film, so this route doesn’t always look like such a certain journey. And given the sheer amount of artists’ film, from low-budget experimental stuff to the sumptuously finished beauty of Matthew Barney’s Cremaster series, there are evidently many working artists out there producing a lot of work that may be destined for brief gallery showings before disappearing into cultural oblivion, with the successful crossovers mentioned above proving extremely rare exceptions to the general rule. Just like Hollywood’s two biggest industries – cinema and porn – the gulf between artists’ films and popular cinema is apparently quite vast, and it is often assumed that both will never meet on common ground.

The Artists’ Cinema project is a collaboration between LUX and the Independent Cinema Office; the project has commissioned new artists’ films which will be screened in cinemas alongside mainstream features. UK audiences will see their latest series this spring, after a preview screening at Tate Modern on 16 April. This follows on the success of their previous collaboration in 2006 when similar commissioned artists’ films were shown in selected venues before such popular fare as Borat, Casino Royale and Pan’s Labyrinth, reaching audiences of 100,000. Whilst such a figure would demoralise the mainstream film industry, it opens up hitherto undreamed-of audience possibilities for artists’ film.

Surprisingly, this may not be such a novel and radical move as it at first appears. Catharine Des Forges, Director of the Independent Cinema Office, explains: “About 15-20 years ago, artists’ films were shown in cinemas, and called ‘experimental’ films – they were a regular part of independent cinema, but now that’s not the case. In the intervening years, artist-filmmakers have become incredibly good at reaching new audiences via more traditional visual arts or gallery contexts, and because of changes in technology, we can now easily get cinema audiences to try and engage with artists’ work. Traditionally, if you showed artists’ films they would all be in the same programme, and marketed to the ‘artist’s audience’ with the same people always coming to watch them – it would be quite difficult to show to another group, and what we now seek to do is a sort of ‘guerrilla’ attempt to hijack new audiences from the mainstream and show them something different.”

Audiences who went to see Borat during the last Artists Cinema season were confronted with Phil Collins’ He Who Laughs Last Laughs Longest (2006), a very short film about a laughing competition, as the opening feature. Although utterly different to Borat, it was unexpectedly and powerfully engaging, getting entire cinemas laughing along and thereby perfectly primed and ready for Sasha Baron Cohen’s grand absurdity. In its own way, this subversive pairing proved that the space between mainstream cinema and artists’ film is not necessarily insurmountable. A surprising phenomenon is the difference of seeing an artists’ film in a cinema rather than a gallery context. In the hallowed space of a gallery, films are regarded with all the usual gravitas of the fetishised art object; in the cinema, audiences are just given the film once and expected to jump headlong into it. Which is, of course, the best way to experience film. Asked if this change in context generally produced noticeable changes in response to artists’ film, Des Forges said: “I think the context is everything. The difference is quite exciting, because most artists are not generally making work to be screened in a cinema. For the artist, it’s a challenge, and for the audience these unexpected out-of-the-mainstream works are something new. If you were to ask audiences if they want to see artists’ films, they might not think it’s for them, but it’s all about terminology, and if things aren’t bracketed, audiences can respond to them in a really positive way.”

Such positive responses beg a consideration of mainstream and artists’ film, and why they are seen so differently. Put simply, an artist’s film could be said to be one made by an artist who has established a fine/visual arts practice, and who is working in the traditions of experimental or avant-garde film, outside of the industrial model of filmmaking, and not part of a historical tradition of filmmaking. This project includes people who have never worked in a cinema before and whose work has been exhibited predominantly in a gallery context or maybe online: artists who are not generally classified as “filmmakers”. Ben Cook, Director of LUX, explains the commissioning process for this year’s films: “We were looking for artists of a certain profile – not completely established, but who are receiving critical attention within the visual arts world and are recognised for working with the moving image. And we felt that they all engaged with the cinematic vernacular in their work, albeit in quite different ways.”

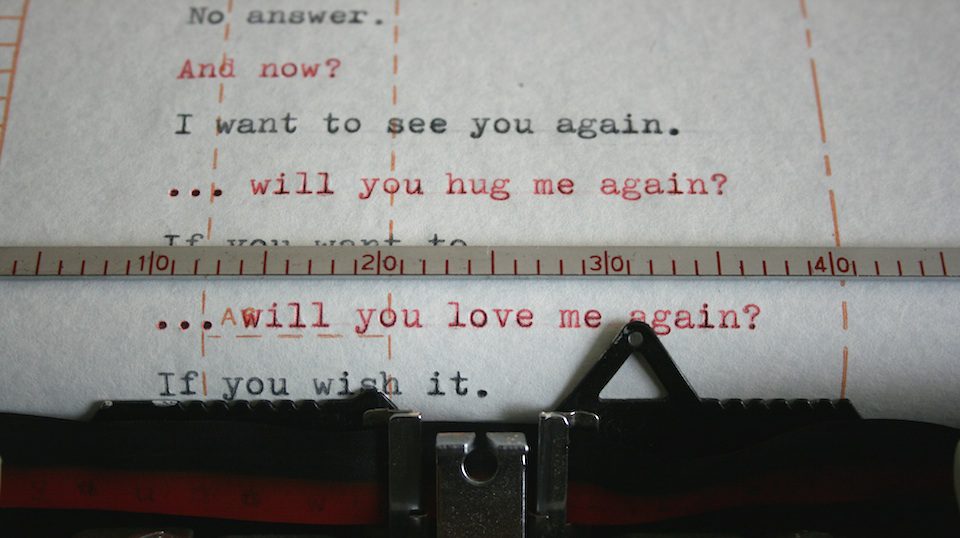

The artists involved with this project are from all corners of the world. Gerard Byrne represented Ireland at the Venice Biennale in 2007, and works in film, video and photography. He has restaged conversations lifted from popular magazines from recent history as a way of highlighting cultural memory, progress and change. Keren Cytter is an Israeli writer and filmmaker who lives and works in Berlin, and whose work reflects the ways in which the media permeate our social reality. Aurélien Froment lives and works in Paris, making film, sculpture and photography installations remarkable for their ability to evoke a sense of loss in the viewer. Amar Kanwar is from New Delhi and has produced some fascinating documentary films about the partitioning of India and Pakistan that highlight both the absurdity and aggression that maintains the political status quo there. Rosalind Nashashibi’s solo show at London’s ICA last year earned her the plaudit in the Observer “one of the best film artists at work in Britain today” for films that mix discreetly shot footage of unsuspecting passers-by with staged vignettes performed by actors. Lithuanian Deimantas Narkevicius graduated from sculpture to making films that question the possibility of being creative and avant-garde in an environment that stifles personal creativity. Catherine Sullivan’s film work has probed the border between innate and learned behaviour, dissecting the idea of “performance”, and she will be collaborating with Farhad Sharmini on a film entitled House of Smoke. Lastly, Akram Zaatari, who lives and works in Beirut, is both a filmmaker and an archivist of Middle Eastern photographic history. The latter naturally informs his film work, which explores post-war Lebanon and the production and circulation of images of the Middle East.

If this year’s crop goes down well with cinema audiences, the Artists’ Cinema could influence the long-term cinema experience. As Des Forges suggests: “Besides bringing artists’ film to new audiences, our aim is also to encourage audiences to look at and seek out new work. We want to make cinema going more interesting. And therefore make cinemas more ambitious in their programming. If artists’ films get a positive response, they might be more open to showing more new, difficult or ambitious stuff.”

The Artists Cinema 2010 launched on 16 April 2010 at Tate Modern. www.independentcinemaoffice.org.uk

David Gleeson