Kelly Reichardt’s fifth feature film, Night Moves, follows a group of three very different left-wing environmentalists as their well-intentioned morals take a terrible turn for the worse.

In the past 10 years documentary has gone mainstream. Assessing everything from the first world obesity crisis, to growing up in British suburbia, real life break-ups and make-ups, and our ongoing, increasingly complicated destruction of the planet, this once niche medium has, through the channels of Netflix and LoveFilm, become just as much of a talking point as the next big television show or Hollywood blockbuster. This plethora of documentaries, and their huge surge in popularity, undoubtedly have a political slant, and are symptomatic of our ability to engage with issues quite apart from our own lives much more than was ever previously possible. However, in spite of a subsequent growth in the “mockumentary”, little of this politicised screen time has yet made its way into scripted feature films.

Night Moves, the fifth feature film from Kelly Reichardt, takes the battle of left-wing environmentalists and interrogates what happens when their beliefs lead them to break the law under the understanding they are making a contribution to the greater good. The subject of environmentalism is a perpetually hot topic, the irreversible damage that mankind has already done to the planet creating a ticking time-bomb and ever-increasing occurrences of climate-change-related ecological disasters as a result of global warming. It is an area that is relevant to us all but to many feels too overwhelming to process or engage with. After all, numerous scientists have already acknowledged that the tipping point has passed and that the best that we and our collective governments can hope for is a policy of damage-limitation. Reichardt herself acknowledges the continual struggle to live and consume well as a first world citizen and the endless battles and hypocrisy involved: “You just realise the bourgeois-ness of going to Whole Foods and buying your organic berries so that you’re going to have the nice thing of keeping yourself healthy by eating organic, but then it turns out these berries were flown on a plane from New Mexico so that I could have them.” Any environmentally conscious citizen will know this dilemma all too well.

However, Night Moves focuses on a motley crew who recognise that living the good life isn’t enough and that action must be taken for people to stand up and take notice. The film follows the idealist, militant environmentalist Josh (played by Jesse Eisenberg) as he teams up with the wealthy but disillusioned Dena (Dakota Fanning) and the reckless, bomb-savvy Harmon (Peter Sarsgaard) to create an act of protest against America’s corporate culture in which people will kill the planet “so they can charge their smart phones.” They buy a boat with cash from Dena’s estranged father, get fake IDs and when Dena manages to persuade a garden store to sell her vast quantities of fertilizer it becomes clear that their plans are fairly ambitious. The three intend to blow up a massive dam, a feat which they pull off with little incident, until they discover, after fleeing to their respective homes, that a nearby camper has been reported missing, and is later found drowned. What follows is a tense, dark portrayal of Dena and Josh slowly falling apart in very different ways. Crippled with guilt, Dena becomes a liability in their small, eco-friendly community, and the pair’s mental breakdown, as well as Josh’s shocking actions to silence Dena, create a dark and intense account of the fragility of human endeavour and error.

Reichardt created the screenplay with Jon Raymond, and says that the initial idea for the film came from Raymond’s visit to a similar community to the one where the story was set. The farm, known as Applegate Valley, is where parts of the film were finally shot and, “it is a place which runs just off rain water and solar lighting and all the housing is built without metal or cement, so it’s a group of super-conscientious people trying to live with the smallest footprint possible.” While “it’s hard to know exactly what idea comes from where,” Reichardt describes living in that area as “sort of the genesis of it. Also, Jon had an idea for a short story of someone who was hiding out on that farm after having done some kind of extreme activity (but where the whole story was taking place on the farm) so that might have been the springboard back in the beginning.” Filming across the beautiful landscape of the American North-West (where Reichardt also filmed her previous feature films), location scouting also proved fruitful in discovering and developing different viewpoints within the characters: “There are so many different points of view that you come across just by spending time with people that you would never normally come into contact with. Your lives probably wouldn’t intersect but you just see how people’s politics are based on such different things, like how they make their money or how they are able to raise their cattle or if they’re allowed to be organic. Everyone’s politics are based on this personal thing, so that all becomes pretty interesting.”

These locations, coupled with the background of the north-west, which Reichardt describes as “the birth-place for the environmental movement in the USA,” created the motivation to explore “the idea of taking on the fundamentalist personality of someone who’s just so positive about their ideology and their intuition. That was the beginning of the Josh character.” While there wasn’t a specific research process, the director’s time at Applegate Valley undoubtedly had an effect on the development of the film. While it poses pertinent questions about how to act for the greater good, and what lengths to go to, her portrayal of environmentalists was not always popular with the whole of the community: “What Josh is doing has a militant element to it and, of course, there’s a lot of dogma in his behaviour, but he’s living in this culture of organic farming, By the way, it should be said, organic farmers are just lovely people. At every Q&A there’s always someone who’s so disappointed in me for showing the Left in any kind of bad light.”

Reichardt also cites her childhood in Miami where her father was on a bomb squad, “during the years of all the hijackings” as inspiration and argues that while her “research wasn’t just geared towards environmentalism, that is certainly an interesting part of it. You kind of start wide and move in closer and closer.” Influenced by groups such as Earth First! and Earth Liberation Front, Reichardt and Raymond nonetheless “wanted to set our story in a post-9/11 world and separate ourselves from those groups just because a lot of those people are serving time [in prison] (for property damage rather than physical harm).” Essentially, it is not only the extremist central characters of Night Moves, but all the environmentalists around them, who struggle with the concept that “if humanity is really going to be driven over the cliff by the sort of industrial powers that be, why aren’t we all out blowing stuff up?” In portraying a community not just of eco-terrorists, but of organic farmers, contributors towards community box schemes and home-grown, home-schooled aficionados, Night Moves acknowledges that “some people find it quite radical to just live in a day-to-day way where they’re completely minding the size of their impact and footprint.”

At the heart of the film is the question about whether a person’s strongly held and earnest beliefs can justify extreme actions, exploring the moral ambiguity between motivations and the acts which can ensue from them. It’s a disjuncture that’s frequently explored in film, but Night Moves is also about the isolation of the criminal and the contrast between “how people are when they’re by themselves versus what happens in a community.” As Josh, Dena and Harmon undertake their attack, Reichardt expertly builds tension and then there’s a sense of euphoria after the explosion has happened. But retreating to their separate homes (and learning of the missing camper) a palpable loneliness and desperation descends on each of the protagonists – and the narrative. The director describes the aftermath as “a sort of vacuum in which all the ambiguities have time to enter your mind and you question what you have just done.” She outlines the process as being like a heist film, “a really articulate frame so that you have gaps within articulated ambiguities.” As a result of this, and the inherent contradiction that the characters want to save the world but instead they cause a large disaster, rather than having a particular message, the film poses “some sort of question.”

What is left intentionally unexplored is how the characters became so radicalised in the first place. As the story evolves, we piece together that Dena is from a wealthy family but dropped out of college and shunned the society lifestyle after becoming increasingly aware of the environmental effects of consumerism, and that Harmon is an ex-military man with a distinctly destructive streak. Most pertinently, however, Josh, the ringleader, is almost a blank canvas. Because of this he becomes the central and most compelling character as he’s so determined to succeed at whatever cost, but is simultaneously disconcertingly insular. Although we learn that he lives and works on an organic farm, we never discover anything about his background, how he became so radicalised, or even if he has ever carried out such significant acts of protest before.

For Reichardt, this is the beauty of film, that it’s “of slices of life, when you join up with people and they’re already on their way to something and we take a ride with them for a certain amount of time.” Although she doesn’t divulge the details, she reveals that the writers created their own back story for Josh but, for her, Josh could just as easily have ended up in a group on the Right as he could a group on the Left. “He just has a lot of anger in him and he is finding something he can feel really right about to vent his rage. Also, I think he feels superior to everyone around him and then that starts to come apart later.” Josh’s motivations are absolutely central to the film because they so powerfully drive the narrative, manipulate the other characters and ultimately contribute to his own destruction. Reichardt describes his act as “like his little 9/11, it’s a statement. It’s not that he thinks destroying one dam is going to actually change anything, but he thinks that people will start doing more of the same and the ripple effect will have started with him. I think he’s competing with the farmer; who advocates environmentalism on a personal level] living your own life well is not enough for the times we live in.”

With statements like this Reichardt has created an inherently political film and, although she and Raymond tried to remove their own politics from the narrative and the sympathy of the screenplay, the descent of Josh and Dena is nevertheless thought provoking. Even from the very beginning their flaws are shown in the way in which they lead their “ecological lifestyle” – they drive a large truck, eat in fast food restaurants and aren’t always as mindful of their consumption as perhaps they should be. But in creating these weaknesses, the script simply helps the viewer to better identify with the characters on-screen. We all try very hard to live better lives but inevitably stumble and have little failures throughout the each and every day.

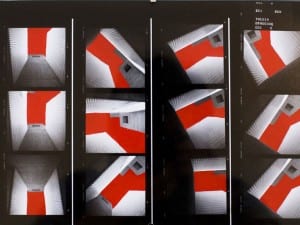

This inherent scepticism and almost nihilism regarding the state of our planet and our ability to change it, make for a dark, tense and deeply demoralising film. Christopher Blauvelt’s characteristic shadowy, almost claustrophobic cinematography adds to the tension and despair of the characters. Blauvelt is well known for being “not afraid of darkness at all” and so the filmmakers “embraced that and it was an exciting sort of thing to try to get a handle on because we had such large spaces and so few resources.” A significant proportion of the film takes place at night, but Night Moves still takes the opportunity to embrace the stunning scenery of the American North-West, as a gentle reminder of everything that the protagonists are trying to preserve.

Ultimately, Night Moves is not a documentary, but it has its roots in fact because it highlights extreme examples of idealistic living. Its ending is so ambiguous (it’s never clear if Josh is turning himself in, or seeking anonymity in one of the very faceless corporations offering the sort of packaged view of the countryside that he has grown to detest), that it highlights that there is no right or wrong answer or way to behave – an issue that will continue to plague us all. Released in cinemas 29 August. www.sodapictures.com.

Ruby Beesley