The exacting Christopher Williams (b. 1956) is equal parts photographer and surgeon. Janus-faced, his glossy photographs are at once ersatz advertisements and visual dissections that repurpose the pictorial-psychological machinery of advertising in order to dismember it. Williams’s ascetic aesthetic mode is the subject of a traveling mid-career retrospective, The Production Line of Happiness, currently on view at London’s Whitechapel Gallery. Executed with technical perfection, the photographs on display clone the coded — clean and frozen — aesthetic of 1960s-style advertising. Some of the more recent works also assume advertising’s production methods, with Williams acting as a “shoot director” in collaboration with commercial photography studios.

However, each perfect photograph actually has at least one tiny, incisive aberration from the Platonic ideal put forth by advertising. Dressed in a bright red Falke sock, a neatly turned heel features a small brown scab; a tire prominently branded “Michelin” seems deflated alongside mental pictures generated by the Michelin Man’s Rubenesque form. Sometimes the so-called flaw consists of artifice laid bare. A woman’s smile is forced too wide in a failed attempt to feign for-profit happiness; the seductive sheen of a sprocketed filmstrip turns out to be a few well-placed strokes of paint. Uncomfortably nestled in advertising’s visual language, these deviations ultimately serve as the punctum (“that accident which pricks me”) that make Williams’s photographs merit a second look.

In Williams’s catalogue-style images, women — like dishwashers and cars — are objects on display, and thus can fall short of an inculcated ideal. (When men feature in his photographs they seem to have more of an instructional purpose, or one supportive of the object on display; a manicured yet masculine hand moves toward the knob of a camera or light meter). In one photograph, a slim woman models a semi-sheer lingerie set. The twist of her body produces folds in her flesh, and her back is dotted with a constellation of moles. When rendered in the style of a catalogue advertisement, these beautiful, normal bodily features feel as aberrant — as ready to be photoshopped out — as the visible binder clips that pull the model’s bra tight across her chest. What comes across as somehow deviant in the context of expectations viewers are led to bring to commercial imagery is telling, and with the photographs of women, disturbing.

Williams makes rote commercial imagery strange; its sealed surface, maintained by visual conventions and implanted ideals, is disruptively loosened or made porous. Relatively less compelling is the retrospective’s thread of institutional critique. The Production Line of Happiness brings norm-flouting exhibition design to arts institutions (the academic Art Institute of Chicago, the high-gloss MoMA, and the public Whitechapel Gallery) in an effort to draw attention to the naturalised codes of the white cube. At Whitechapel, the deviant retrospective is in reverse chronological order; it has, in lieu of wall text, large Fujifilm-green strips and lingering snippets of text from the gallery’s prior exhibition, Adventures of the Black Square; and its mobile walls, some of which have been flown in from a previous show in Germany, are marked with bits of masking tape, scribbled shipping instructions, and drilled holes. The critique of arts institutions feels outdated, having itself undergone thorough art world institutionalization. There are far more current, interesting, and radical ways to comment on the power that arts institutions wield in framing the reception of art and art history, if that somewhat hermetic concern happens to be one’s thematic nucleus. With Williams clearly benefitting from the art world machinery on top of it all, the institutional critique put forth by the exhibition design, while visually well-executed, lacks the cogency and nuance of its photographic counterparts.

Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness, until 21 June, Whitechapel Gallery, 77-82 Whitechapel High St, London, E1 7QX.

Cassie Packard

Credits

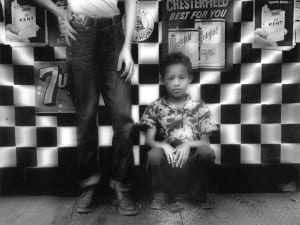

1. Christopher Williams, K-Line, Matt Dulling Spray, CFC Free … Studio Rhein Verlag, Düsseldorf, August 24, 2014 2014 Private Collection, Germany Image courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne and David Zwirner, New York/London.