There is more to Allen Jones than those tables. As if to acknowledge this fact, the curators of this retrospective have placed two of them right at the beginning of the exhibition. Once the shock and awe is over, the show unfolds to reveal the unfailing ingenuity of a British Pop artist who turns out to be both a brilliant painter and an incisive critic of modernity.

Jones stands out from his contemporaries, such as Patrick Caulfield and David Hockney, by taking Pop in a slightly darker direction, delineating it more as a style than a subject-matter. In the work of his peers, Pop appears with the freshness of an obsession with consumer goods and the lifestyle afforded by the trappings of late capitalism. But Jones takes it in a different direction by analysing the ideas behind these things. Consequently, his work is reflective and critical in a way that now feels exceptional in the entire Pop movement.

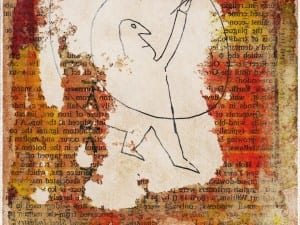

The early paintings, such as Interesting Journey (1962) and The Artist Thinks (1960), show the pictorial influence of surrealism with the colour of abstract expressionism. Jones takes these influences in a novel direction by emphasising the dominance of the human figure. This is how he explores the relationship between the sexes and the deconstruction of Western society in late capitalism. Night Moves (1985) depicts an unsettling scene in which a mermaid is crucified, where the men’s faces are conspicuously blurred or missing altogether, with only the women granted facial features. It is difficult to know what he is saying here, but not as awkward as it is with those poor mannequin women supporting a tabletop on all fours in their lingerie. Jones is playing a dangerous but tantalising game: he is not depicting the world, he is making manifest in art its ideologies.

The surface of Jones’ paintings combine radiant colour with a soft focus effect, sometimes interrupting the pristine flatness with harsh brushstrokes and incongruous deposits of pigment. Strange Music (1977), for instance, feels as if frustrated follower of Greenberg had a moment of abandon. The relationship between Jones’ painting and sculpture is seamless: the painted sculptures leap from the paintings that surround them, giving the room the depth and energy of a crowded ballroom. This continuity is followed through to its logical conclusion in the furniture sculptures which are an evolution of the paintings’ obsession with the female figure and attempts to depict the mores of contemporary society.

And then the ugly, inevitable question arises: on which side of the line between thoughtful critique and outright misogyny does Jones stand? There has been a lot of liberal outrage over this exhibition, denouncing Jones as a woman-hater and questioning the RA’s integrity for staging the exhibition. If you shut out that moralising noise, you can see that while Jones makes deliberately provocative work that frustrates interpretation he always just manages to render his position ambiguous by the fact that the sculptures are more grotesque than anything else. Faced with the shock of the grotesque, it is difficult to know how to take it, but it is certain that Jones’ skill for creating an aesthetic surface with sufficient depth to provoke debate makes him one of the few truly critical artists of his generation.

Allen Jones, until 25 January 2015, Burlington Gardens, Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Daniel Barnes

Credits

First Step, 1966. Oil on canvas, 92 x 92 cm. London, Private Collection. Image courtesy of the artist. © Allen Jones.