A major three part retrospective of artist James Turrell displays his pioneering explorations of light, space and time.

We spend our lives immersed in ever-changing environments of light, where no two moments are ever quite the same. Whether it’s a cloud acting as a gauze over the sun, a glorious sunset or a total eclipse, we tend only to notice the most pronounced effects of light, and ignore the constant flux of conditions that plays out in our everyday existence. However, it is just these shifts in our perceptions that the work of Arizona-based artist James Turrell (b. 1943) has been drawing attention to for over half a century. Creating work with light as its principal medium and object, Turrell makes immersive environments that encourage the viewer to be more aware of changes in the illuminated landscape and, by extension, the act of observation itself. Currently the subject of three major exhibitions at The Guggenheim in New York, The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the artist’s hallucinatory, epiphanic and sublime installations are being recognised as among the most searching and affecting of our time.

Turrell has been exhibiting groundbreaking work since the late 1960s. His first solo exhibition at Pasadena Art Museum in 1967 established his reputation, and the consistency with which he has investigated his chosen materials of light and space has been one of the defining facets of his practice ever since. The works from this period were from the series Projection Pieces , in which light projected onto the corner of rooms created a dramatic sense of floating shapes of colour. For example, Acro Green (1968), which is included in The Light Inside at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, presents both a rectangular form and peripheral oval shapes in a saturated sci-fi green. Illusory and intransigent, these pieces seemed to bend the possibilities of what could be achieved through Turrell’s chosen medium, and were the beginning of his artistic explorations of our perceptions and overall reaction to light as an art form.

Prior to this, Turrell had trained not as an artist, but in the disciplines of mathematics, astronomy and perceptual psychology at Pomona College, before changing direction and enrolling on a graduate art programme at the University of California, Irvine. As Museum of Fine Arts Houston curator Alison de Lima Greene remarks: “There’s an almost physical engagement with colour and light in his work. His pieces enact not just an emotional response to colour but a sharpening of all of your perceptual faculties. After you have spent some time looking at Turrell, you walk out and pay attention to how even an ordinary lightbulb casts light upon the wall, or how the sky changes not just at sunset but constantly throughout the day and night.”

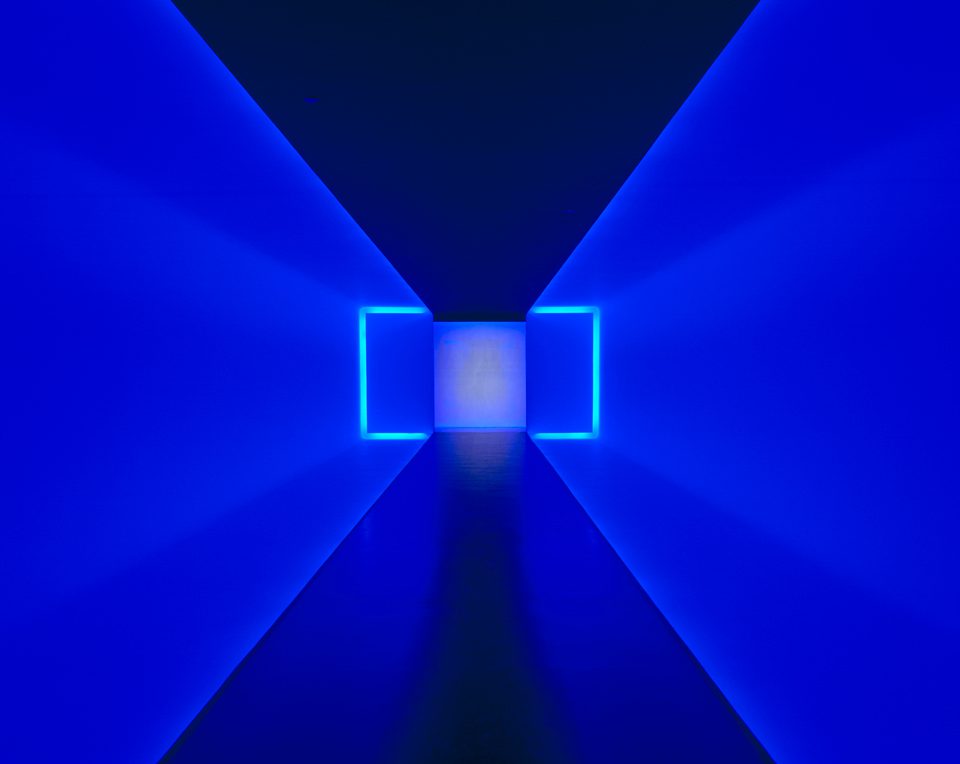

The Houston exhibition is largely curated from the museum’s important collection of Turrell’s work, prominent amongst which is the permanent installation The Light Inside (1999). Installed within the Wilson Tunnel linking the museum’s two art spaces, The Light Inside acknowledges the tunnel’s function as a liminal “between space.” However, rather than serving as a utilitarian conductor of visitors from one gallery to another, the tunnel enacts a transition from one perceptual state of mind to another through the saturation of neon and ambient light along the its walls. The raised floor gives the suggestion of being suspended within space so that walking through the Wilson Tunnel is almost like being transported within a radiant beam.

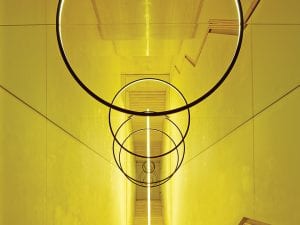

As part of the tripartite retrospective, The Guggenheim in New York is presenting Aten Reign (2013), the largest temporary installation ever to feature in the Frank Lloyd Wright designed rotunda of the museum. An enormous, glowing, cosmos-like structure consisting of six individual ovoid forms, Aten Reign goes through an hour-long cycle in which a chromatic spectrum unfolds from hidden LED lighting. Running the gamut from lurid to delicate, from being seemingly drawn from nature and seemingly drawn from the saturation of cinema, Aten Reign explores the effects of colour on our perceptions. Designed as an immersive experience, the piece engages the viewer in a profound sensory involvement that is difficult to resist. While clearly creating a suggestion of the sublime, Turrell’s work is incredibly subtle and delicate. What might at first be experienced by the viewer as awe or amazement softens through the duration of the piece into self awareness and a heightened sense of consciousness. The element of time is important because it allows viewers to become aware of, and observe, their own responses to light conditions.

Turrell has described this process of self-realisation in his work in the following terms: “My work has no object, no image and no focus. With no object, no image and no focus, what are you looking at? You are looking at you looking. What is important to me is to create an experience of worldless thought.” Culture is saturated with images. We are almost invariably looking “at” something: a screen, a painting, a photograph or an object. This is particularly true of and intrinsic to the apprehension of artworks where there is an object – “the artwork” – to be observed. However, in Turrell’s work, this perceptual relationship is as intransigent as light itself, fracturing in the act of perception.

The Guggenheim contextualises this important new work by presenting it alongside a number of early works by Turrell from the 1960s, such as The Single Wall Projection Prado (White) (1967), which creates a disarming sensation of the dematerialisation of space. The light in this piece appears to erase the boundary of the wall and hint at a transcendent space beyond. These works help to locate Aten Reign within the artist’s ongoing use of installations. However, his investigation of viewing and colour has also been realised through works on paper and in other media. Also being displayed is a selection from the portfolio of etchings First Light (1989-1990), in which Turrell explores qualities of luminance, contrast and radiance inherent within the aquatint technique. Given his interest in our perceptual relationship to properties of light and exposure, the etching process itself has affinities with the artist’s wider practice, with projection an analogue for the printing process and in which it is what has disappeared that creates the artwork.

While the Houston exhibition presents a carefully considered cross-section of Turrell’s work, and The Guggenheim shows ambitious new works, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is concurrently staging a full-scale retrospective of his career featuring over 50 pieces. Christine Y. Kim, exhibition co-curator and Associate Curator at LACMA, comments: “There is nothing like the experience of a Turrell work, which is truly about and for the viewer and his or her perception. Perception is the medium for Turrell, as his work provokes viewers to see themselves see.”

Among the pieces included at LACMA are works that investigate our perception of darkness and light, including the installation Light Reignfall (2011). This work emerged from earlier collaborations with artists Robert Irwin and Ed Wortz and presents a “perceptual cell.” Entering an enclosed space horizontally on a bed, the viewer is immersed in a confusing and disorienting space of saturated light. However, one of the fascinating things about this work is the way the eye and the brain adjust to the conditions and are able to adapt perceptually. A similar experiment is Shallow Space Constructions (1968), in which Turrell uses light to transform the way we perceive depth in a large room.

Turrell’s work grew out of the Light and Space Movement, a term for the practice of artists such as John McCracken, Doug Wheeler, Eric Orr, Ron Cooper and Robert Irwin. Their simple minimalism, suggestions of immateriality and landscape, and use of new technologies came to characterise the dominant artistic vocabulary of Southern California, or what is sometimes referred to as “the LA look.” However, while Turrell’s work demonstrates some resemblances to the work of these other California-based artists, his deep investigations into sensory perception and the psychology of light owe as much to explorations into the multiple histories and traditions of his chosen medium.

An inheritor from great painters of light and perception such as Caravaggio, Turner, Vermeer and the Impressionists, and an abstract expressionist who has exchanged the canvas and paint for a purer exploration of light and space, Turrell builds upon and extends the practice of these artists. In particular, his work draws on the paintings of Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman. For example, Tycho White: Single Wall Projection (1967), on display in Houston, specifically references Newman’s “zip paintings”, which featured expanses of colour with thin, differently coloured vertical lines. In Turrell’s work, the thin “zip” is a strip of light rather than paint. However, just as the exact and precise line of paint in Newman’s work is in some sense an illusion of precision masking an intricate dynamic of colour, in Turrell’s Tycho White the zip has an aura surrounding it. It is perceived as a thin line but in fact there is an oval glow around it.

However, as de Lima Greene has remarked, Turrell’s influence from artistic traditions goes much deeper and wider than that, drawing as much on the impulses of “the creators of Stonehenge and the pyramids” as on the relatively narrow history of Western painting.

These diverse inspirations are perhaps nowhere more evident within Turrell’s practice than in his large-scale masterpiece Roden Crater . Since the early 1970s, the crater in Arizona has been carefully worked over by Turrell to create an extraordinary piece of land and light art. Sculpting and adapting the natural features and conditions of the extinct volcano itself, the artist has created a number of different transitional spaces such as tunnels, pathways and ante-rooms. Within these spaces, Turrell has developed the most complete expression of his series of “Skyspaces”, portals or boxes such as windows and frames. Constantly in flux because of ever-changing conditions of the sky, these simple framing devices reveal ravishing and extraordinary abstract works of dynamic colour and saturation. Depending on the position of the light, it is possible to perceive stars and planets – miniature packages of the cosmos within these envelopes of space.

Roden Crater is, in a sense, both a temple and a monument, though without the specificity that either of those terms suggests. Dependent on the light it manipulates and engages with, providing sublime effects, Roden Crater is always changing and never defined. As such, it is perhaps more appropriate to consider it as an observer’s post, somewhere to approach without a specific idea of what is to be apprehended, but with a willingness for, and openness to, perceptual experience. Across the over two dozen installations that will be presented in Roden Crater when it is complete, the viewer is encouraged to engage in an act that humans have been interested in for millennia: looking up towards the light. It is at once moving, romantic and self-aware.

Of the expressive and poetic qualities of Turrell’s art, the critic Jonathan Jones has remarked (Guardian, 2000): “Turrell is the last great American romantic artist, giving the viewer rhapsodic encounters with nature and the mystery of light. He proves that artists can still look at nature afresh.” By intervening in natural light conditions through meticulously planned installations, Turrell encourages us to observe ourselves in the process of observing and, by doing so, he transforms our relationship to perception in general. While this is a revelatory process in many ways, he is able to avoid the grandness that this suggests through the minimalism and intransigence of many of his works. These three important surveys of Turrell’s work demonstrate that he is still creating visionary interventions to help us quite literally “see the light.”

James Turrell: The Light Inside runs until 22 September at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (www.mfah.org), James Turrell runs until 25 September at The Guggenheim, New York (www.guggenheim.org) and James Turrell: A Retrospective runs until 6 April 2014 at the LACMA (www.lacma.org).

Colin Herd