Text by Franziska Knupper

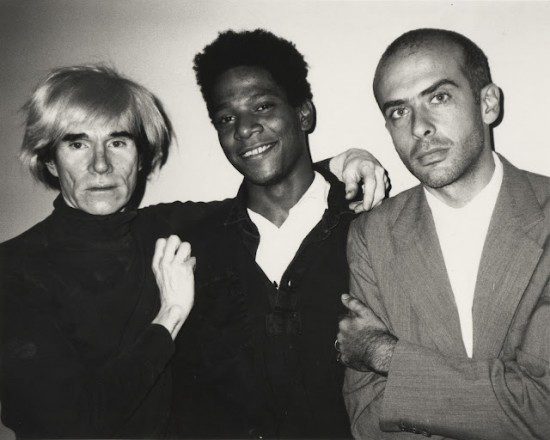

Campbell’s soup cans, exclamation marks, kissing couples. Warhol, Basquiat, Clemente. The works of three legendary artists are currently being displayed at the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn. Under the title Ménage à Trois the museum presents the artists’ fascinating collaborations during New York’s thriving art scene of the 1980s; how they inspired one another and contributed to each other’s work or, as Andy Warhol himself put it: “One’s a company, two’s a crowd, three’s a party.”

The group met in New York. Warhol, known for his eccentricity, was already a notorious and internationally renowned artist whilst Clemente, just having returned from his travels to India, spent his days as a visitor at Warhol’s famous Factory and Basquiat was a 23-year-old kid from Brooklyn painting t-shirts on the street. Their styles always differed profoundly from each other. There are Basquiat’s furious faces with the narrow eyes and the music notes coming out of the mouths; faces like colourful masks from African Tribes or from urban Graffiti walls. Even visitors who are not familiar with Basquiat’s work will recognise his stylistic traits after having looked at only a couple of pictures; the scratches, the writing, the torn-up pages of magazines. Energy and dynamism become almost visible, touchable. Small segments of bright colours are divided by black and yellow lines. Lines are cutting into fields of paint, leading you to swear words in bold print, screaming at you: “Hey Suckers!”

Spending time with Basquiat’s work you can feel the city, the hustle and bustle, the aggressive forms and overwhelming patterns. His pictures are full of youth, of speed, the rush of the metropolis, of his past as a street artist. In comparison to Basquiat, Warhol’s images almost appear clean and controlled with precisely defined shapes, serial graphic elements and repeated themes and sizes. There are his popular portraits of Goethe or his Jackie Kennedy prints; there is the soup, the banana, the Mona Lisa.

According to Basquiat, it was usually Warhol who started the process. He would provide the basis; a headline or a theme and Basquiat himself would then just “scribble and sketch something on it”. He modifies them, attaches a moustache to the full lips, draws tiny figures in the corners or writes messages in red letters only to cross them out afterwards. He adds his impulsive spirit, a taste of trash and punk to the orderly atmosphere of Warhol’s images.

Clemente’s contribution to the collaboration follows in the last hall of the museum. Already a first glance at his pictures will tell you that his vision differs profoundly from the urban hastiness of his fellow artists. His style does not waver between impulse and control but rather focuses on the surreal and the mystical. His broad brush strokes resemble Edvard Munch, lacking the clear outlines of Warhol and Basquiat. His figures seem to merge while kissing; the canvases remain without the slightest hint of uncoloured space. Everything is filled and connected, slightly blurry, otherworldly.

In his case there already seem to be several souls and styles united in the spirit of this one painter. Clemente uses various materials ranging from oil or acrylic to watercolour; he employs bright colours as well as sinister tones, draws faces overlapping or merging into each other. His works are visions, are fusion, are dreams. Not surprisingly, a collaboration with the other artists only felt like a natural “extension to himself”. This collection of several identities was only a logic result of his work. For him, the contradiction and differences between their styles only contributes to the strength of the paintings. In contrast to that, Warhol remarks that the best pictures are those where it is impossible to tell who created a certain element. The spectator might disagree with him on that aspect – no one would ever confuse a clean image of Warhol with Basquiat’s wild scratches.

Despite those different aspirations and styles it is a collaboration in which every artist respected the other’s opinion, work and approach. In the last corner of the exhibition visitors can have a look at the portraits they created of each other; they can admire Basquiat’s portrayal of “Warhol as a Banana” and have a look at the mutual portraits and photographs in white overalls and with boxing gloves. They all examined each other as painters, as personalities. It is a display of reciprocal appreciation, of sensibility and understanding for each other’s work; of respect and friendship. It is also a presentation of an era of unique artistic productivity, of velocity, of Bebop Jazz and Velvet Underground at the same time. It is wild, it is noisy. It is the New York City of another decade with its flashing headlines, streets and brands. It is New York City with its roughness and the fragility of its metropolitan inhabitants; inhabitants like Warhol, Basquiat and Clemente always on the hunt for identity, for orientation, for collaboration.

Ménage à trois: Warhol, Basquiat, Clemente, 10/02/2012 – 20/05/2012, Bundeskunsthalle, Museumsmeile Bonn, Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 4, 53113 Bonn. www.bundeskunsthalle.de

Aesthetica in Print

If you only read Aesthetica online, you’re missing out. The February/March issue of Aesthetica is out now and offers a diverse range of features from an examination of the diversity and complexity of art produced during the tumultuous decade of the 1980s in Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, opening 11 February at MCA Chiacgo, a photographic presentation of the Irish Museum of Modern Art‘s latest opening, Conversations: Photography from the Bank of America Collection. Plus, we recount the story of British design in relation to a comprehensive exhibition opening this spring at the V&A.

If you would like to buy this issue, you can search for your nearest stockist here. Better yet call +44 (0) 1904 629 137 or visit the website to subscribe to Aesthetica for a year and save 20% on the printed magazine.