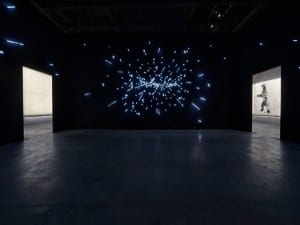

Bob Dylan, known more so for his poetry, music and writing, began introducing his artwork to the world with an exhibition of his Drawn Blank Series in 2007 at the Kunstsammlungen in Chemnitz, Germany. The exhibition included over 200 watercolours and gouache paintings made from original drawings. Within the last six years he has exhibited his drawings and paintings time and time again in some of the world’s most renowned museums and galleries such as the National Gallery of Denmark, the Gagosian Gallery in New York, Milan’s Palazzo Reale and last summer at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Now, Dylan exhibits his most recent sculptures at the Halcyon Gallery in London. The seven gates, glass-top tables and wall hangings made out of iron and vintage objects collected by Dylan resonates the death of industrial America. With this immaculate exhibition it is as if Dylan is returning back to his childhood town of Hibbing, Minnesota; the motto of which is “We’re Ore and More”. Since Dylan has decided not to give any interviews in relation to Mood Swings in order to let the work speak for itself, we had a interview with Paul Green, the Director of the Halcyon Gallery.

A: What kind of influence would you say Dylan’s music has had on your life?

PG: On me? Personally none. So when we were first approached, it was about the calibre of the art. It wasn’t about the music for me. When you start then really looking and researching, watching the movies then you realise the extent of his influence on the world. Dylan is one of the greatest influences in the 20th and 21st centuries.

A: What are your thoughts on Mood Swings?

PG: The Halcyon has been working with Bob Dylan for the last six years. The first exhibition we held was Drawn Blank. It was in a museum in the east of Germany and the recognition for it was unprecedented. Since then really, it doesn’t matter what I think. The reaction from many of the greatest critics in the world as well as the exhibiting museums has been enormously positive. The National Portrait Gallery recently exhibited his work. So I think what we like at Halcyon is for people to walk through the door and decide for themselves. Of course, I think the work is amazing since I’ve been working with Dylan for the last few years. When I saw the ironworks I was literally stunned.

A: Many of the renowned artists of our day have had formal art training. I think Dylan doesn’t necessarily, and many people in the art circles could possibly say that a musician should stick to his job, make his music, and shouldn’t diverge. What are your thoughts on this?

PG: Dylan has drawn from day one. He has always been totally versed in the arts. He has been fascinated by both painters, writers, musicians and he has practised his craft. Because he has been on the road since he was 20 he has never stopped drawing. And those drawings were really what were chosen by museums effectively as his way of almost distilling what he’s been doing on the road as well as his reflection of humanity, places and people. I think the same still carries on. Many artists are multi-disciplined, some more so than others. As I said I think it’s for the rest of the world to decide the extent of his talent. I think there is no question about it when it comes to Dylan. He is not only a great musician and poet but also a great artist.

A: In the post-modern world of our day there are people from many different social classes and statuses buying more art work than ever before. Would you say that this so because people are more educated about art today or would you say that buying art is still a symbol of status and power?

PG: I think, from my point of view, having started off selling art in very different circumstances to now, it is amazing if you give people the opportunity to look at art, to be involved and just how important it becomes in people’s lives. It’s the same in the amount of people who visit museums and shows, who want to be involved in public art. I think it just the natural progression of an open society. I am sure that purchasing for investment purposes still goes on but I prefer it if people come through the door and want to see the art first of all and then of course buy the things that they really like.

A: Who would you say will be the clientele of this work?

PG: What we saw in the Drawn Blank series was that people from all around the world, of all walks of life were interested. It’s impossible to pigeon-hole the buyers, nor would I want to. It’s extremely diverse and you’d be amazed as to how many people would want to acquire something just because they have literally fallen in love with it. Remember these things can also go outside; many of the artworks can be placed outdoors. Then it becomes personal for the person who owns it.

A: To what extent would you say the works in Mood Swings resonate Dylan’s ideology in life?

PG: Again, I can’t speak for what Dylan thinks. He never explains what he does but as he said, the critical issue is that the ironworks go back to where he was born. He has collected all of these objects from all over America, gathered what were used by working men and women. He has effectively taken these objects from an industrial bygone age and resurrected them into an object really deeply personal. I think it’s for the viewer to decide themselves what story they want to tell because he would never want to give you his story in relation to the works. He wants you to put in your own story.

A: In what genre would you classify Dylan’s artwork?

PG: He is a living contemporary artist. I don’t think he would classify himself at all.

A: So you wouldn’t say he is an abstract expressionist?

PG: No, I would say he is Bob Dylan.

Hande Eagle

Mood Swings, 16 November until 25 January. Halcyon Gallery, 144-146 New Bond Street, London, W1S 2PF. www.halcyongallery.com

Credits:

1. Bob Dylan at his iron works studio, September 2013 © John Shearer

2. Gate 1 © Bob Dylan/Halcyon Gallery

3. Bob Dylan at his iron works studio, September 2013 © John Shearer