Standing in the entrance of Grayson Perry’s exhibition at the Victoria Miro gallery I find myself caught between two images. On the left, a child is cradled in the arms of a young mother. She sits in a pub-carpeted, patterned wallpapered, trinket adorned room, the time-honoured depiction of working class living (The Adoration of the Cage Fighters, 2012). Two bald, tattooed men worship at the ginger-haired baby’s feet. They present gifts of a miner’s lamp and Sunderland football shirt. In the image to the right a man lies dead, cradled in the arms of a paramedic on the pavement of a London street (#Lamentation, 2012). A smashed sports car provides evidence of the accident. His curly ginger hair echoes the infant’s.

The images are woven; the walls of the exhibition hung with six, two by four metre tapestries. They bear an immediate correlation of baby pinks and blues, chalky purples and yellows, and dusky oranges. Not only is this clearly a singular work presented in six parts, but the colours fill the room with Grayson Perry’s unmistakable aesthetic stamp. The tapestries fulfil their traditional role of historical document and storyteller. Their episodic narrative is loosely based on William Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress (1732-33), eight paintings that tell the story of a man, Tom Rakewell, who finds his demise through the accumulation and subsequent consumption of wealth. Following on from Hogarth’s depiction of current class culture in the original paintings, Perry renames the character Tim, and uses the relationship between taste and class as it exists in contemporary culture to generate imagery and update the tale.

Perry’s compositions borrow notably from Christian Renaissance painting, and as such each tapestry holds an unspoken religious overtone. The cage fighters adorning the baby with gifts are Mantegna’s shepherds before Christ (The Adoration of the Shepherds, 1450) and when Tim’s family shuns him, he and his girlfriend walk away as Adam and Eve in Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (1424-28). The archetypal Biblical scenes are so present in compositional history that the connection is not laboured. The presence of religion in the images allows one of Perry’s key themes to surface. In his second tapestry, The Agony in the Car Park (2012), Perry’s narrative voice openly states, “Ship building bound the town together like a religion”. The classes depicted in Tim’s narrative are tribal; Systems of belief that imply more than simply social standing. Other than wealth and social division, for Perry they contain a system of taste that comes to pervade many aspects of life, from choice of lifestyle, clothes and furnishing, to preference of celebrity chef.

Whilst Hogarth’s character inherits his money, Perry’s protagonist generates his own fortune. An intelligent lower class boy who, rejected by his mother, finds himself accepted in his girlfriend’s middle class family. His own earnings then catapult him to bourgeois wealth. The penultimate tapestry, The Upper Class at Bay (2012), shows Mr and Mrs Rakewell walking in the land around their austere countryside mansion (referencing Mr and Mrs Andrews, Thomas Gainsborough, 1748-9). A group of protestors is encamped upon their vast lawn. Their placards declare “Tax is good” “Pay up Tim”. In the foreground of the image the most extravagant image that the tapestries afford, an absurd tartan stag staggers across the scene, chased by slavering, scarlet hell-hounds. Perry’s take on class is anything but impartial.

At the far end of the space, separate from the tapestries, sit three of Perry’s signature pots, placed alongside two drawings. The pots, like the tapestries, present a fragmentary view of modern taste. However, in this case Perry’s diverse set of references is tied down by theme rather than narrative. Voting Patterns (2012) surveys the UK’s popular political landscape, stopping by Thatcher’s link to the “Baby Boomers” and ending up at a direct transfer of the now ironic sign “Liberal Democrats Winning Here”. The Existential Void (2012) takes a jab at the intellectual classicism of the art world, declaring itself a “META pot” and pointing out the art-culture faux pas “Picasso napkin syndrome.”

The drawings, depicting more pots, continue this line of thought. Entitled Tate Pot and RA Pot (2012) they align the art institutions with their perceived equivalent level of branded goods. Whilst Tate finds itself compared to the distinctly middle-class lifestyle of Apple, Sainsburys, Jamie Oliver, and John Lewis, the RA is represented by a more gentrified list, amongst them: Boden, AGA, Liberty, Radio four, and of course, Waitrose. The drawings are an effective visual one-liner, but also serve to bring the art world into the class discussion, a self-acknowledgement necessary to prevent the exhibition tipping too far into the self-righteous. Returning to Perry’s final tapestry I notice a final twist. In the background of the iconic image (borrowed from Weyden’s depiction of the death of Christ, Lamentation, 1441) is a BP petrol station and to its left a McDonalds. These at first incongruous buildings, present a final reference to the art gallery. I walked along City road, past the scene of the accident, on my way to the exhibition.

Grayson Perry: The Vanity of Small Differences, 07/06/2012 until 11/08/2012, Victoria Miro Gallery, 16 Wharf Road, London, N1 7RW. www.victoria-miro.com

Credits:

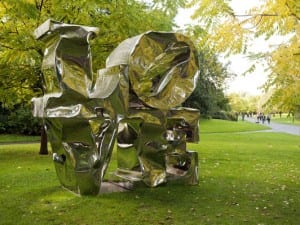

Installation View, Grayson Perry The Vanity of Small Differences, Victoria Miro Gallery, 7 June – 11 August 2012

Text: Travis Riley