Ai Weiwei is a master craftsman. Over the years, some critics have suggested he is a great activist but not a good artist. However, Weiwei’s work in porcelain, marble and wood, in particular, is astonishingly complex and comparable in vision and execution to the design talents of Leonardo Da Vinci. Running at the Brooklyn Museum until 10 August, Ai Weiwei: According to What? surveys a wide selection of the artist’s work from 1983 to the present.

The links between Weiwei and Da Vinci come to the fore in Divina Proportione, a handcrafted Huali wood hollow polyhedron named after a maths book written by the older artist. This choice highlights Weiwei’s nod to their shared enthusiasm for maths and also subtly challenges notions of history and authority. Da Vinci’s sources of inspiration were often knowledge systems ancient to his time and original to Asian and African societies, transmitted to the West through oral and materially recorded form. With this in mind, the audience could ask whether Weiwei referring to this history, and if the process he used to create this work predates the Renaissance. There is a kind of solace in viscerally experiencing the perfectly proportioned Divina Proportione and its sister polyhedron F Size. Both are in the first gallery of the exhibition, displayed casually on the floor, as if they had randomly rolled there, much like the cats’ toy they are modeled upon might also be found in a home.

Ai Weiwei: According to What? spans two floors and includes sculpture, video, photography and large-scale installations (there are also two pieces near the entrance of the museum). Many works fall between categories. Teahouse, for example, a one tonne house of compressed tea, sits in a small field of tea leaves in a closed off enclave. It is sculpture and installation simultaneously; the teahouse a distinct entity yet an integral component of a larger composition. The audience is asked to imagine many small rooms within the house. But, the overriding question is to inquire about “according to what” notions we imagine. It is the structural efficiency and sense of internal order to Teahouse that is striking and that is the sensibility which permeates the show. Even Weiwei’s chaos is orderly, like the infamous dropping of an ancient Chinese urn — he may be shattering conventions, or have other disruptive intentions, but the process is captured and framed impeccably within a triptych.

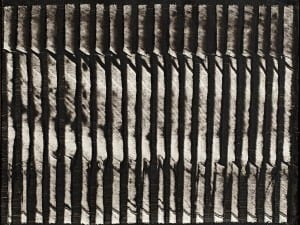

His work is also humourous, and points to the comedy within otherwise chaotic (sometimes dangerous) realities. This is the case with the 3,200 variably sized porcelain crabs in a heap on the floor, called He Xie. The title is a dual reference to the Chinese Socialist Harmonious Society, a brainchild of former paramount leader Hu Jintao and “he xie,” a word that means both “crab” and “harmony.” The latter meaning is coined by China’s netizens to outwardly reference censorship covertly: a censorship that is part and parcel of the political processes of creating the official Socialist Harmonious Society. Such puns and double/triple entendres resonate throughout the show, especially in video. While the exhibition is so vast, dense and detailed, it can be summed up succinctly as a window into objects both classical and modern, that disrupt and remake while rendering in highly cultivated form.

Ai Weiwei: According to What?, until 10 August, Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11238.

Odette Gregory

Credits

1. Ai Weiwei (Chinese, b. 1957). He Xie, 2010. 3,200 porcelain crabs, dimensions variable. Installation at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C., 2012. Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio. Photo by Cathy Carver.