In the 1930s, the US was struggling through the Great Depression. A new show at The Art Institute of Chicago looks to the creative spirit of the era, highlighting vernacular artwork and documentary photography. Aesthetica speaks to Curators Elizabeth Siegel and Elizabeth McGoey about the exhibition: Looking for America in the 1930s.

A: Can you describe the cultural landscape of the US in the 1930s?

ES/EM: Economic instability inspired calls for national unity. In the art world, artists, curators, collectors and government administrators attempted to define a distinctly American visual identity. They located in the fields of documentary photography and American vernacular arts – which they called folk art – a national culture they considered egalitarian, unpretentious and self-made.

A: How did the Great Depression create an impulse “to record the present and collect the past”? What types of artworks were the result?

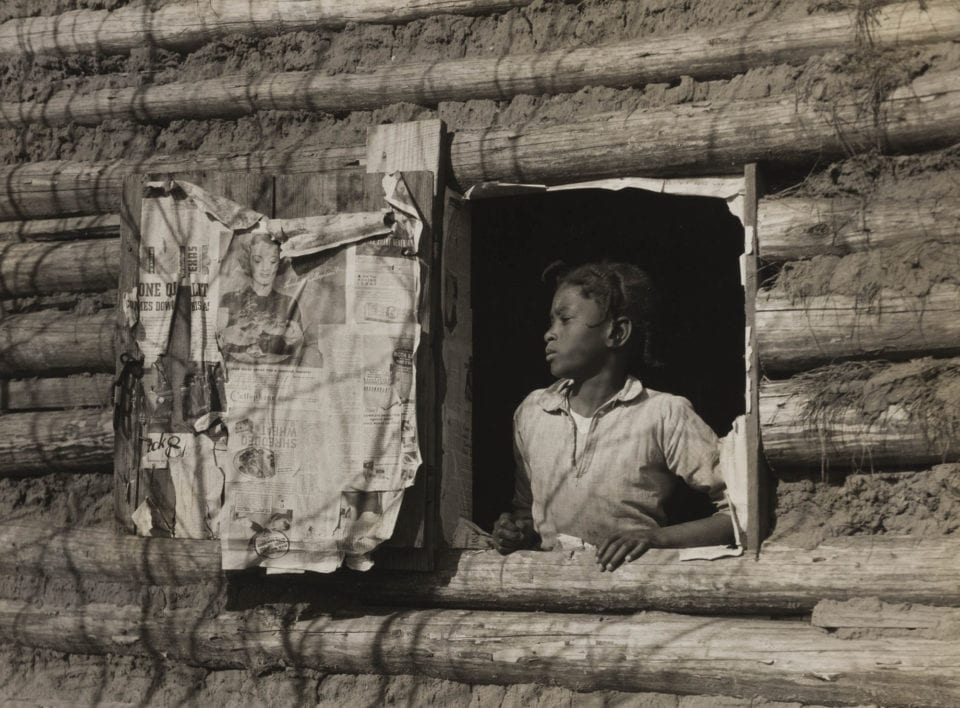

ES/EM: It is impossible to underestimate the devastating effects of the Great Depression on peoples’ livelihoods and sense of stability. Yet this crisis also fostered the urge for people to pull together, to make sense of the world around them, to find emblems of the nation that signaled a hopeful future. American vernacular arts are not a result of this crisis – most of the objects in the exhibition are from the 18th and 19th centuries – but they did take on new meaning. At the same time as Americans began examining and collecting these earlier arts, documentary photographers started recording the contemporary state of the country. Under the government’s employ, photographers such as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Ben Shahn documented the plight of poor Americans devastated by the effects of the Depression as well as the everyday activities of middle-class folks, depicting society with clarity and dignity.

A: How does the exhibition combine the two artistic areas of photography and folk art?

ES/EM: The exhibition places the works together through historical and thematic connections. The first gallery, for example, frames documentary photography and folk art through the lens of a 1930s impulse to document and index America’s visual culture on a comprehensive scale. Both the WPA Index of American Design and the FSA photography project sent artists out into the field to record the character of the country, resulting in enormous repositories of American material and visual culture. In the second gallery, we examine how both photography and folk art expanded the canon of traditionally high art as they entered the museum virtually simultaneously; these effects continue to resonate in fine art collections today. Later in the exhibition we explore themes of America’s usable pasts (looking at both colonial and nineteenth-century source material for a 1930s sensibility) and continuing vernacular traditions in the 1930s (works with humble material origins) to explore ties between photographs and objects. Across all the galleries, the perceived authentic, unadorned, and egalitarian aesthetics of the photographs and the folk-art objects resonate with each other.

The Art Institute of Chicago, through prior gift of Simon and Bonnie Levin.

A: Can you explain a little more about the FSA? How did this initiative impact the evolution of photography?

ES/EM: During the Great Depression, the federal government employed some of the country’s best photographers, who produced nearly 80,000 images of American life. These photographs, made between 1935 and 1942, form an enduring national catalogue of the devastating effects of the economic catastrophe. Under the umbrella of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Resettlement Administration (1935–1937), later reorganized as the Farm Security Administration (FSA; 1937–1942), provided relief to Americans who had lost their farms, homes, or jobs. Roy Stryker sent photographers to various regions with a rough itinerary and extensive instructions on what to shoot. Although the artists maintained their own stylistic approaches, the FSA prioritized humble, quotidian realities, journalistic clarity and dignified portrayal of suffering and self-sufficiency alike. Stryker shared with the photographers, journalists and publishers of his time a strong belief in photography’s ability to catalogue humanity and preserve human experience. FSA photographs were kept on file and made available for educational and civic purposes, as well as to interested members of the general public. Many images appeared as newspaper illustrations, magazine covers, or in photobooks.

A: Can you give some examples of artists whose work is on view?

ES/EM: Walker Evans helped to define a documentary tradition in photography, cataloguing the American scene with a dispassionate approach that was precise yet poetic. Evans was captivated by the variety of American vernacular expression, turning his camera toward subjects as diverse as hand-painted signs and movie posters, roadside fruit and vegetable stands, storefronts, main streets, gas stations and cars. Other examples include Berenice Abbott. As other photographers documented the plight of Americans around the country during the Depression, she trained her lens on the dramatic transformation of New York. Returning to the city in 1929 after eight years in France, she purchased an 8 × 10–inch camera and began to document the city’s architecture, storefronts and transportation.

A: What do you hope viewers take away from the show?

ES/EM: We are having this discussion on 29 October 2019, which marks the 90th anniversary of the stock market crash. Yet the questions that drove this exhibition are still relevant today: What role should the government play in supporting the arts? What constitutes fine art, and what belongs in museum collections? And how do we define an American visual identity? You won’t find all of the answers in the exhibition, but we hope these questions, and the works on display, linger in visitors’ minds long after they leave the show.

Until 19 January 2020. Find out more here.

Lead image: Walker Evans. Alabama Cotton Tenant Farmer’s Wife, 1936, printed c. 1962. The Art Institute of Chicago, restricted gift of Mrs. James Ward Thorne. © Walker Evans Archive, the Metropolitan Museum of Art.