The gig economy is a “labour market characterised by the prevalence of short-term contracts or freelance work, as opposed to permanent jobs.” In the UK, this encapsulates 2.8 million people, with roles spanning transport services, food delivery, digital roles and content creation. It’s almost impossible to know how many people work in these positions worldwide, although some estimates put the numbers as high as 1.5 billion. Photographer Salvatore Vitale presents an exploration of how the gig economy is reshaping labour and revealing the contradictions of digital capitalism. He uses film, photography and installation to document the everyday realities of people whose lives are increasingly governed by algorithmic control. Photo Elysée presents SABOTAGE, a new exhibition from the artist, which centres South African freelancers who remain central to digital economies. The show unfolds as an immersive experience, beginning with a corridor that evokes a corporate environment, progessing through fragmented workspaces and culminating in an e-waste scene. Aesthetica caught up with Vitale to discuss why he chooses to focus on the labour force and how art can be a tool for social reform.

A: How did you first begin working behind the lens?

SV: It started when I was working as a researcher on a project that used photographs taken by children to understand how they perceived their surroundings, which was a specific region in Switzerland. We gave disposable cameras to young people between three and seven years old, and they produced more than 5,000 pictures. I found that engaging with this material sharpened my awareness of photography’s aesthetic force, but also revealed the power of images to construct meaning rather than merely record reality. I became very excited about the medium. Like many people starting out, I bought a cheap camera and began experimenting, spending a lot of time in the darkroom and shooting portraits, something I rarely do now. It was a process of defining what my voice could be and what I might contribute to the field. As time went on, I grew interested in how the camera could be used to narrate stories, whilst mixing approaches, from speculation to documentation to fiction. I moved to include other perspectives and media, making use of moving images, new-image making techniques, writing, installation and sculpture.

A: Who, or what, are your main creative inspirations?

SV: I am a very curious person, so they come from many directions, from literature to design and scientific writing. Anime and animation, as well as certain subcultures such as cyberpunk or afro- and sinofuturism, for example, are important references for me, not in terms of direct quotation, but in how they construct worlds and narrative logics. For my most recent project, I was deeply influenced by several writers who deal with tsimilar subjects to me, like Frantz Fanon, Achille Mbembe, Nick Srnicek and Gavin Mueller. Their writing helped define the conceptual and political dimensions of my work. Hito Steyerl has also been a long-term inspiration for me, both visually and conceptually. The works of Walid Raad and Harun Farocki are a sustained source of inspiration for the way they construct narrative within an unstable, ambiguous space. I have always admired Martine Syms, Zach Blas and Lawrence Lek in the contemporary field. At the same time, I remain deeply connected to more canonical histories of photography. Robert Frank and Allan Sekula, for instance, remain a foundational reference for me.

A: Tell us about SABOTAGE. How did the project first come about?

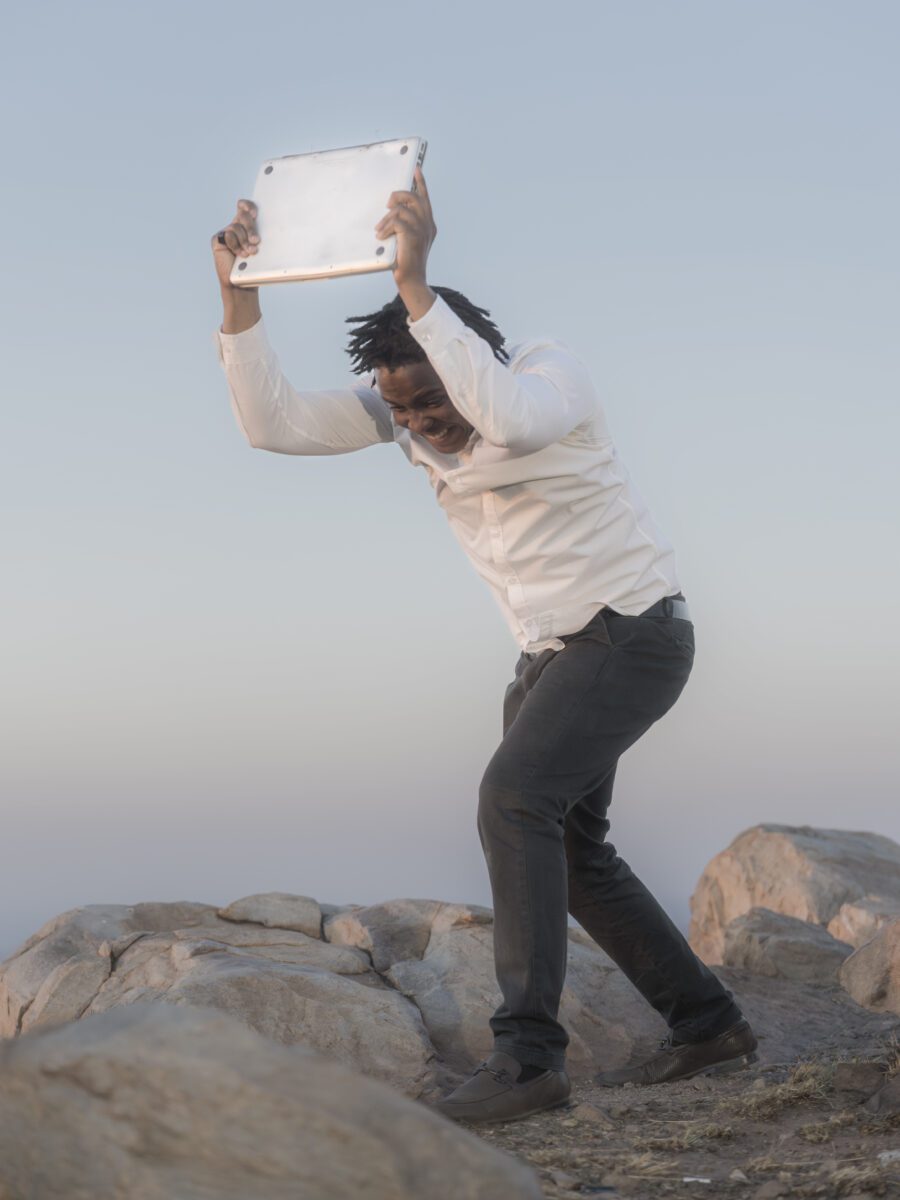

SV: The exhibition at Photo Elysée marks the first time I will present the entirety of Death by GPS, a project developed in South Africa over the past four years. The project considers the gig economy, the rise in automation and how these economic structures are exploitative, particularly for workers in the Global South. It’s structured around the notion of “sabotage” as a set of everyday strategies through which people navigate, resist and subtly interrupt these systems. It began with a personal interest, as my grandfather was actively involved in labour rights through the Italian Communist Party, and questions of work, exploitation and collective struggle have long formed part of my intellectual and political horizons. I wanted to shift attention to the human labour that sustains the institutions we rely on in our everyday lives. I was also interested in the more collective dimensions of sabotage and protest: how people imagine forms of solidarity, collective action and resistance within conditions that are designed to isolate workers from one another. South Africa’s long history of labour struggles, combined with its post-Apartheid context, shaped both the ethical and political dimensions of the work. Death by GPS places contemporary digital labour against the backdrop of older colonial and extractive histories, drawing parallels between historical forms of exploitation and their platform-based mutations. The mechanisms may have changed, but the underlying logics of control, extraction and asymmetrical power relations remain persistent.

A: The show’s title suggests an act of disruption. What, for you, most urgently needs to be challenged within the gig economy?

SV: There is substantial work to be done at the level of legal frameworks to counter exploitative dynamics, particularly given that many platforms are headquartered in the Global North while operating extensively in the Global South. Questions of jurisdiction, regulation and accountability across national contexts remain largely unresolved. The gig economy includes many different realities, from delivery services to creative labour, yet across these contexts, the need for fair pay, rights and the ability to claim them remains fundamental. Ultimately, the struggle is about the possibility for workers to collectively demand and enforce those rights within systems that are structurally designed to prevent such collective agency.

A: You’ve said that digital capitalism offers the promise of greater freedom and flexibility to mask the persistent inequalities of post-colonialism. Tell us more about that.

SV: The dynamics I observe often reproduce, in updated form, very classical colonial patterns: infrastructures and platforms are designed, owned and governed in the Global North, while they are sustained by labour performed in the Global South. This asymmetry is further reinforced by disparities in wages and by the fragmentation of work into micro-tasks, which renders workers increasingly interchangeable and disposable. Flexibility is often presented as empowerment. But when you analyse how platforms communicate, what is sold as freedom can quickly become exploitation. Algorithmic systems monitor performance. Workers must remain constantly available. Remote work does not necessarily translate into quality leisure time. This dynamic becomes particularly acute in contexts such as South Africa, where structural unemployment remains high, and the labour market offers limited protection. Platform labour is therefore often perceived as an opportunity, sometimes the only viable source of income. The promise of opportunity becomes a mechanism through which exploitation is normalised.

A: You worked closely with freelance workers in South Africa on this project. How did collaboration shape the direction of the series?

SV: It was at the very core of the project. Without collaboration, I could not have developed a meaningful understanding of the conditions under which people work and the complexity of their everyday struggles, strategies and aspirations. What began as a methodological approach quickly evolved into a genuinely collaborative process. The project was developed through shared making, dialogue and negotiation, rather than through a one-directional flow of information. This process of shared authorship became a means of engaging more deeply with the political, social and affective dimensions of digital labour.

A: SABOTAGE spans photography, video and installation. How do you determine which medium should be used to express a particular idea?

SV: I always begin with the story, never with the medium. Each subject suggests its own form of narration. For me, the choice of imagery emerges from the complexity of what I am trying to articulate, rather than the other way around. Sometimes photography is unable to address what I need, especially when something cannot be seen, such as invisible processes, structures that cannot be directly represented, or dynamics that exceed what a single image can hold. Sometimes this means working with film, where dialogue, sound, and rhythm allow for a different kind of temporal and emotional engagement. At other times, it means constructing an experiential or installation-based environment that enables the audience to inhabit the dynamics of a situation rather than simply observe it from a distance. I also think a lot about the space. Even when presenting photographs, I try to design an environment because the setting contributes conceptually to the work. Research, storytelling, design and production happen simultaneously. Installation is therefore not just a mode of presentation for me, but an integral part of the work’s conceptual framework. This spatial and narrative thinking runs parallel to my production process. Research, writing, storytelling, design and production evolve together.

A: Your work often starts with systems, security, algorithms and labour that are designed to be unseen. How do you render the invisible, visible?

SV: Many systems governing modern life rely on invisibility. You should sense them, but not see them. This is true for security systems, rating mechanisms or algorithmic management. Over the years, I have developed strategies to approach this problem, always beginning from a strong narrative and research-based foundation. I do not approach photography as a medium that documents reality in a one-to-one manner. From the outset, my relationship to the image has been grounded in its interpretive potential. This openness is crucial to my practice. On the one hand, I am proposing a particular reading of a topic, often one that differs from how these issues are framed in other fields. On the other, I want to create conditions for the audience to enter the work at different depths, to move through layers of meaning according to their own curiosity and experience. Facts and fiction often operate in parallel. Each project begins with extensive research and close engagement with real conditions, but I allow myself to fictionalise certain elements in order to open up additional layers of understanding, ways of thinking and feeling through the subject that would not be accessible through factual description alone.

A: How do you view art as a platform for promoting social justice?

SV: I do not consider myself an activist. However, I do believe that cultural production, regardless of its form, is a powerful terrain in which questions of social justice can be articulated and contested. Culture has the capacity to narrate the world differently, to offer alternative ways of understanding realities that are usually mediated through news cycles, policy discourse or institutional language. At the same time, it is difficult to claim that artistic practice can directly “change the world.” Yet if we look at the history of art and culture, we can trace small, dispersed moments; sparks, rather than grand gestures, that gradually accumulate and contribute to broader shifts in how issues are perceived or discussed. My own position is modest in that sense. I am not working with the expectation of producing immediate change. Rather, I aim to address social and political issues that matter to me and that I believe are shaping the world we inhabit, and to propose alternative narratives around them. If there is an ambition, it lies in creating awareness. What happens beyond that point is not something I can control. The hope is simply that this awareness can circulate, resonate and perhaps be taken up by others. Wherever possible, I try to make elements of my work available for use in other disciplines. This includes collaborations with academic institutions, NGOs and organisations that engage with similar issues. This kind of exchange extends the life of the work beyond the exhibition space and allows it to operate within broader networks of social engagement.

A: What’s next for you? Are you working on anything new?

SV: Right now, my focus is on what comes next for Death by GPS, including exhibitions and screenings. This moment of transition, when a project leaves the studio and enters different public contexts, is itself an important part of the process. Every project leaves me with topics I could not fully explore. I see these as starting points for future projects rather than unresolved leftovers. I tend to work in this cumulative way, allowing one project to generate the conceptual and thematic seeds of the next.

Salvatore Vitale: Sabotage is at Photo Elysée, Lausanne 6 March – 31 May: elysee.ch

Words: Emma Jacob & Salvatore Vitale

Image Credits:

1&6. Salvatore Vitale, untitled, 2022, from the series Death by GPS, 2022 – 2026 © Salvatore Vitale.

2. Salvatore Vitale, untitled, 2023, from the series Death by GPS, 2022 – 2026 © Salvatore Vitale.

3. Salvatore Vitale, Lethabo, Web Designer, 2024, from the series Death by GPS, 2022 – 2026 © Salvatore Vitale.

4. Salvatore Vitale, Bianca, Contractor, 2024, from the series Death by GPS, 2022 – 2026 © Salvatore Vitale.

5. Salvatore Vitale, Automated Refusal, 2025, from the series Death by GPS, 2022 – 2026 © Salvatore Vitale.

7. Salvatore Vitale, untitled, 2022, from the series Death by GPS, 2022 – 2026 © Salvatore Vitale.

8. Salvatore Vitale, Automated Refusal, 2025, from the series Death by GPS, 2022 – 2026 © Salvatore Vitale.