The calliope of the Steamboat Natchez sounds out twice a day, to the delight of tourists strolling New Orleans’ French Quarter. The tune is cheerful, iconic; it’s the sonic equivalent of a slice of pecan pie, washed down with a glass of Bourbon. However, during the final weekend of the city’s triennial of contemporary art, Prospect 4, the steamboat’s call will be answered by an unsettling echo from across the Mississippi: the sound of The Katastwóf Karavan, a calliope conceived of by the artist Kara Walker and installed on the area of land known as Algiers Point.

Located on a bend in the river, Algiers Point was where newly arrived slaves were detained before being ferried across to the French Quarter to be sold. And yet the sound of the calliope is not a lament or a dirge – instead, witnesses will hear strains of Sam Cooke and Jimi Hendrix, and new compositions by the jazz pianist Jason Moran. The Haitian Creole word “Katastwóf” could almost be the sound of an emission of steam – but listen closely, and it speaks catastrophe.

Kara Walker is known for her paper silhouettes which combine the saccharine and the horrific in their uncompromising representations of the black body. Similarly, The Katastwóf Karavan amplifies the dissonance between pleasurable nostalgia and sickening truths – the result is an urgent call to consciousness. And yet, part of the power of that outcry comes from the pleasure it provokes; the mythological muse Kalliopē was, after all, “beautiful-voiced.”

As such, the calliope is an appropriate closing note for an exhibition in a city where aesthetics cannot be divorced from politics. The map of the city encompassed by Prospect – radiating out from central venues such as the Ogden Museum and the Contemporary Arts Center, north to NOMA, east to the Old US Mint, and disseminating into dozens of smaller venues and satellites – is a map which traces the history of the city. Yet the burden of history is also the medium for eruptions of creativity, as suggested by the exhibition’s title The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp.

The title is a reference to the emergence of jazz in New Orleans, a phenomenon which the saxophonist Archie Shepp termed “a lily in spite of the swamp.” In the context of Prospect 4, the lily morphs into a lotus, a symbol of beauty and resilience. However, the title has come under some criticism. Who says the lotus can be distinguished from the swamp? As international artists flock to the city, there’s an uncomfortable sense that the “lotus” of acceptable artforms might be being imposed on a swampy grassroots artistic practice. However, by bringing in the work of artists from across the world, with a particular emphasis on the Global South, Prospect 4 reproduces the conditions which made New Orleans such fertile ground for creativity in the first place; a port city where paths converge, creating a hub of indissoluble hybridity.

Prospect 4 is a rare thing; a triennial which manages to be both internationally relevant and deeply rooted to place. When the directors Trevor Schoonmaker and Ylva Rouse commissioned artists such as Kara Walker, John Akomfrah and Mark Dion, they made sure to introduce them to the lie of the land; its geography and ecology, its history and contradictions. In response, Akomfrah created a video installation which reimagines the life of the musician Charles “Buddy” Bolden, whose experiments with improvisation brought jazz into being.

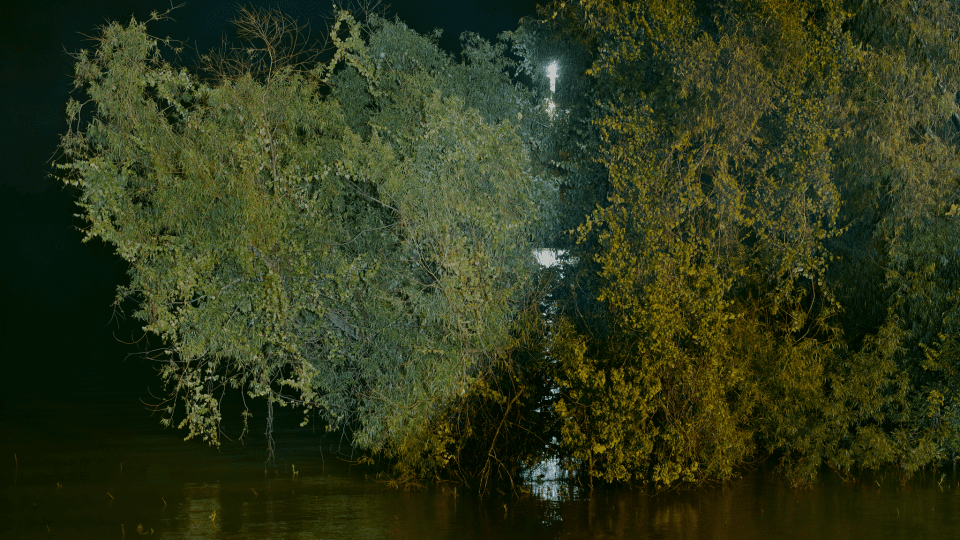

The title of the installation, Precarity, questions the narrating impulse and casts us instead “in the break”– and Mark Dion’s installation Field Station for the Melancholy Marine Biologist takes a similarly precarious position. Located in the batture, the unprotected land between the levee and the Mississippi, the hut is an eerily static reconstruction of a scientist’s workplace. Who is this King Cnut, waiting out existence on a shore threatened by rising sea levels? Is he making a stand against environmental destruction? Or is he simply a victim of artistic hubris?

That attitude, that precarity, is what makes Prospect different from other citywide exhibitions. So close to the water, it is difficult to put much stock by material possessions; likewise, artworks resist the stability that is required of commodities. When the curator Dan Cameron initiated Prospect in 2007, the city was still recovering from Hurricane Katrina; since then, the triennial has both fueled and benefited from urban renewal, and in 2015 coincided with the euphoric celebrations a decade after the storm. Today, however, even as the city jubilantly marks its tricentenary, it is faced – as we all are – with a period of unprecedented political and ecological instability.

Where does art stand in all of this? In the break, on the brink, in the batture. At Crevasse 22, a satellite venue in St Bernard Parish, the New Orleans-based artist Robert Tannen presents his “invisible” boat: a shrimp trawler painted black and transformed into a stealth vessel. This is one of the starkest yet most conceptually rich works in the exhibition – a functional object frozen into an artwork, a fact made invisible in the light of day. Yet this is not the sort of artwork which “heals”. Instead, it asks hard questions about the distinction between art and life, stasis and migration, the seen and unseen. Similarly, Prospect offers no solutions or easy healing. Instead it proposes a commitment to vision, and to questioning. Which is to say, the first steps towards sustainable survival.

Prospect 4 runs until 25 February. For more information click here.

Matilda Bathurst

Credits:

1. Jeff Whetstone, The Batture, 2017.