Chen Ke, one of China’s new generation of young artists discusses her work, the dichotomies of identity, personal tastes and cultural significance in the flux of modern China.

China is by far, one of the most intriguing countries in the world. For decades it was closed, creating an air of mystery and becoming somewhat of an enigma. What did we know? It was big, it was communist, and that was about all. After the end of the Cultural Revolution and the death of Mao Zedong, China had experienced a decade (1966 – 1976) of social, political, economic chaos and disarray.

Collectivisation and forced labour lead to tens of thousands of displaced individuals, communities and consequentially values, history and heritage – many factors that infuse a culture’s sense of identity. One of the main concerns of the Cultural Revolution was the abolishment of the Four Olds: Old Customs, Old Culture, Old Habits and Old Ideas. As a result of the Destruction of the Four Olds campaign, churches, temples, mosques, monasteries and cemeteries were closed, books, artefacts, historical archives and antiques destroyed; throughout the ten-year period, education came to a virtual halt.

Much of China’s past was erased. As the country began to recover from the Cultural Revolution and make sense of past events, another shift in Chinese society occurred, the overwhelming power of globalisation and urbanization. In 1979, Coca-Cola enters the market, the 1980s introduces American cartoons such as Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Mickey Mouse, 1987 sees Kentucky Fried Chicken open its doors in Beijing, the 1990s brings imported films like Forrest Gump, while in 2001 China enters the World Trade Organization.

With such an awe-inspiring transformation within a generation, China has become a major player in the world economy in both production and consumption. This position is not to be taken lightly, in only 50 years there have been two extremes, resulting in nothing happening organically. In one corner, a society loses its cultural past, and in the other, the shift from agriculture to urbanization has occurred virtually overnight.

The art that a society produces says much about its inner-dynamic. Along with China’s economic boom through manufacturing and industry, its art market has rocked the imagination of collectors and enthusiasts. Aesthetica had the chance to catch up with one of China’s most prominent and emerging artists. Chen Ke is a woman of her times, while her images of young girls represent the multiple dimensions of human nature.

Born in Tongjiang in 1978, Chen Ke grew up as only child, in a small town in the southwest province of Sichuan. In 1993 at the age of 15, she moved to Chongqing to study painting formally at the Middle School of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute. This was also the same year that for the first time Chinese artists were selected for the Venice Biennale. Like many young people, Ke went on to university, and finished her studies in 2005 with an MFA. An exciting year for Ke, she also married artist, Cao Jingping, and moved to Beijing, where she now currently lives. Beijing is a powerful force for contemporary Chinese art, Ke says: “My move to Beijing was motivated by the lack of an arts scene in Chongqing. I am now accustomed to living in Beijing and feel lucky to be working here as a free artist.”

Ke’s references to cartoon art are obvious when analysing her works in more detail, elements of Western masters and that of traditional Chinese paintings become visible, which creates an exciting tension. Keen to experiment, Ke often surprises her viewers. Reminiscing back to childhood, Ke’s mother worked in a bookstore where “she gave me a series of 15 comic books based on well-known Western fairy tales and fantasy stories. There were stories included like Alice in Wonderland. With these illustrated stories, I learned to read. For me, it’s incredibly interesting how words and images come together.” Ke’s other great influences come from the 19th Century German painter, Caspar David Friedrich, but also, “classical Chinese masters from earlier times, for example, Zhao Ji, one of the emperors in the Song Dynasty (960 – 1127) who had an important influence on Chinese classical art.”

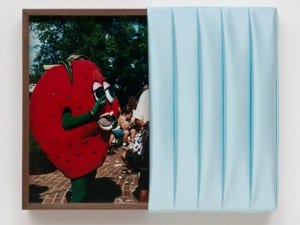

Ke is an innovator. Not only does she manufacture her own paper, embroider canvases with beads, but she also applies oil colour on stretched cotton fabrics, which were popular in her childhood days. “Most often I work with canvases and linen, but I have also worked on a variety of other materials. Once I created a series where I painted on furniture from the 1970s, which I purchased at flea markets. I have also painted with watercolours on stones or used modelling paste and colour on shells. For paintings like If I’m not working, I lose confidence and the feeling of security (2008) or Clockwork (2009) I used printed calico fabrics that show motifs that I have liked since I was a child. Researching different materials is part of my creating process and full of pleasant surprises.”

One manifestation of China’s economic transformation is the power of its contemporary art market. Contemporary art is soaring; the first commercial gallery to open was in the 798 district in Beijing in 2002, now there are over 200 galleries in Beijing and Shanghai, giving artists more opportunities to exhibit and sell their work. Chinese artists are leading the way, taking Chinese culture and critique around the world. The tension that exists between socialist ideals and the new wave of consumerism, the result of many capitalist reforms, is present in much of contemporary Chinese art; it resonates in the global context and leaves a lasting legacy. Ke’s work debates with this idea. “The China I grew up in is completely different from the China I live in today. China has changed in many aspects ranging from politics to economics and a change in the Chinese culture is no exception. However, things are connected to each other and it’s not always easy to narrow it down to only one factor. Specifically regarding culture, I think that for many years there was a strong focus on Western culture and that everything that came from the West was considered as new, exciting and good. I think this attitude has changed, as people re-orientate themselves towards the Chinese culture and tradition. We are getting more and more proud of our own centuries of culture.”

With the ever-increasing interest in contemporary Chinese art with artists achieving lucrative sales at auction, and even Zhang Xiaogang, joining the millionaire club with the likes of Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons, there is something inherently different about contemporary Chinese art. It strikes a chord, opens a door, analyses the present and looks incredibly inward, however it’s unassuming, powerful and at the same time universal. But how does this effect the type of art being produced? “It certainly influences the speed of production by the artists. Knowing that there is a high market demand, a lot of artists are trying to quickly fulfil this demand and deliver artworks. Also, you can observe that if some (older) artists are successful, their style or elements of their style will be copied, or to put it more neutrally – inspire younger artists. Maybe this is not so different to what happened with the Leipzig School. Neo Rauch’s style became very obvious in the works of other artists. For me, I am very happy that I can follow my style and ideas.”

This surge wasn’t always the case, as Ke remembers, “there wasn’t always so much attention on the Chinese art scene. When I began, or even still during my studies, we never could have imagined that the situation would develop to how it is today. I think the attention on Chinese art is also connected to the general attention on China. With China’s development in economics, a greater interest in China emerged, but also in particular on Chinese art. This field was neglected for many years, and then in 2004 people realised that there were exciting things happening in the Chinese contemporary art scene.”

Ke’s work is dreamlike, mystical and enigmatic. Her visual language is profoundly subjective, while aesthetically, her work provokes certain emotions; that of loneliness, sadness and despair. These negative emotions have a greater impact in the context of the modern world. Symbolically they reflect the current state of affairs, the economy, fear, isolation and the sentiment that although the “world is smaller”, we have never been more alone.

One of Ke’s most striking images is Another me in the world. It’s reasonable to muse, what it must be like to have a double – to be you, but someone else at the same time. Of this paradox Ke says: “I felt lonely growing up as an only child. I think there is something funny and magical about having a twin. In order to not feel so lonely, I created another me in the world.” The glance from self to self is utterly compelling. She wants viewers to look within themselves: “I take the inspiration from my heart. I believe my pictures develop from the inside out. It’s an exploration of my inner-self.” It would be easy to dismiss such overt sentimentality, but Ke’s genuine approach makes her work more precious with every gaze.

If I’m not working, I lose confidence and the feeling of security (2008) is existential, capturing the essence of modern living. “I like the contrast of the fragile girl mixed with this rough machine. The machine is used to make handy-works, and in the past, artists created these works with their hands. This is my understanding of being an artist; perhaps it’s a bit old-fashioned. This work, in a way, depicts the tight relationship between myself and my art,” enthuses Ke. With her candid approach and reflective aesthetic, Chen Ke’s work exists in that space between the subjective and the objective, always exploring and conquering new things.

Another me in the world was Chen Ke’s first solo exhibition outside of China. It opened at Kunstverein Viernheim, Germany, between 19 June -18 July 2009. The exhibition included 20 paintings ranging from 2004 to 2009. www.kunstverein-viernheim.de.

Cherie Federico