“To make a long story short, I’m not a very organised person.” So opens Bruce Gilden’s (b. 1946) latest monograph – a collection of negatives documenting 35 years of living in New York.

In a self-proclaimed “cleaning frenzy,” Gilden came across a hoard of cardboard boxes containing 2,000 rolls of film from his old loft. In 2018, he took on the role of the “anthropologist” – unweaving and dissecting a tapestry of moments from the city. The selected images, taken between 1978 and 1984, depict a bygone era, one which captures the surreptitious, accusatory, ambivalent or questioning gaze of strangers.

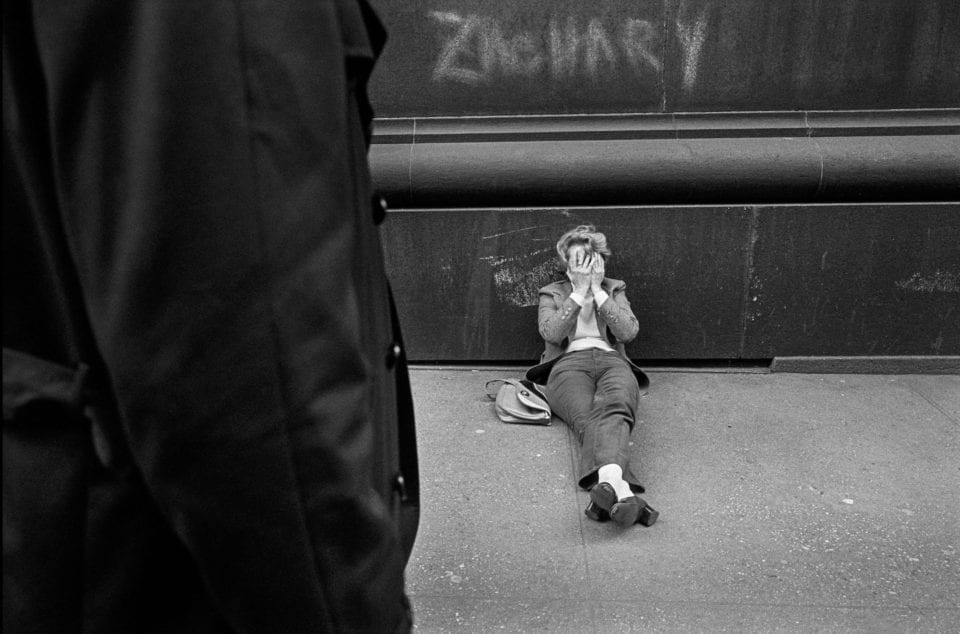

In photographs where the subjects are unaware, individuals lean, face in hands, against graffitied concrete; two men lock eyes and grab each other’s throats; a passenger looks solemnly out from a rolled-down window, flicking ash from a cigarette. Gilden continues: “I like to say that street photography is when you can smell the street and feel the dirt … You feel the sweat, the sleaziness, you feel the tension. It was raw, violent and filthy but it had lots of soul.”

After starting out studying sociology at Penn State University, Gilden quit academia to become one of the world’s best-known, and largely self-taught photographers, celebrated for these honest and raw depictions of humanity and the evolving street culture. Lonesome but determined, he pursued image-making against all odds, supporting himself as a taxi driver. Through these decades, the swell and pressures of the city descended onto Gilden, and as he professes he “was an extremist. I almost died on drugs – but I wasn’t going to let myself fail.”

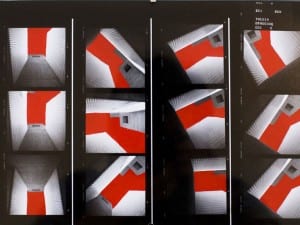

Despite the drive to succeed, Gilden reflects upon the self-conscious and self-deprecating parts of his practice. He discarded and abandoned these photographs, favouring more “energetic” works that had a clearer sense of composition and staging. These negatives, which feature blurred arms, swaying bodies and fuzzy imperfections, were hidden – buried – and long-forgotten. He notes: “I don’t understand how 40 years ago I had overlooked these images as though I thought they didn’t deserve to be printed. I have always considered myself a good editor, so why did I overlook this early work?”

Perhaps the answer lies in the passing of time. Why do Stephen Shore’s classic cars and Joel Meyerowitz’s Dairy Queen snapshots endure beyond their attention to composition, colour and form? For the same reason that Gilden’s suited, pearled and hair-rollered community still fascinates and satisfies. In a world that’s rapidly becoming globalised and gentrified, we revel in the era of the “other” and its unattainable memory – without smartphones and their disassociated owners. As a captivating collection of memories from New York at the turn of the 1980s, Gilden aficionados and first-time viewers will be equally glad that these unseen negatives were, indeed, “found” and published now, rather than never.

Bruce Gilden has worked on projects across New York, Haiti, France, Ireland, India, Russia, Japan, England and the USA, producing 20 monographs and exhibiting at MoMA, New York; V&A, London; and the Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Lost and Found‘s interview excerpts are conducted by Sophie Darmaillacq, Gilden’s wife. The publication is available from Éditions Xavier Barrall.

Kate Simpson

Credits:

1. Bruce Gilden, USA. NYC. 1981.

2. Bruce Gilden, USA. NYC. 1982.

3. Bruce Gilden, USA. NYC. 1978.