Architecture of London at Guildhall Art Gallery takes an extensive look at a continually transforming city, presenting 80 works from the 17th century to the present day. Elizabeth Scott, Head of Guildhall Galleries, City of London Corporation, discusses the show – revealing how artists continue to interpret the city and its buildings.

A: The exhibition chronicles London over 400 years. What is it about the city’s architecture that is so influential to artists?

ES: London’s architecture is so distinctive, and yet no one style defines it. I think this appeals to artists because, no matter what your influences are, you will likely find something in London’s cityscape to inspire. For some people, it’s the changing nature of London’s landscape, which has characterised the capital for over 400 years. Many painters have captured its constant state of redevelopment, from its construction to its destruction. Others are inspired by the views out of their windows, representing everyday life. Although many of the scenes are curiously alienated, a portrait of humankind is created through the most human of environments – suburbia.

A: How does Architecture of London create dialogues between 17th century and contemporary artworks?

ES: The changing nature of London’s skyline means that multiple lines of connections can be made from the 17th century to the present day as similar themes come around again. Whilst the same subjects which inspired artists four centuries ago are still prevalent today, the results can be vastly varied and exciting. For instance, the second section of the exhibition, Changing Landscapes of London, explores how artists continue to be drawn to capturing London in transition. In 1666, artists painted accurate portrayals of the devastation of the Great Fire, whilst the destruction of the Second World War inspired a range of responses – from straightforward literal depictions, to metaphorical representations of the ruins and rubble, used for emotional effect.

The first section, Views of London, creates a dual narrative between early 17th century panoramas of the city by visiting artists, and looks at how London and its architecture is still a source of inspiration for visiting artists today. It explores views across London, as well as artists’ personal views of the city.

Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London Corporation

A: What are the types of artworks on view, and what different views of the landscape do they portray?

ES: The exhibition explores over 400 years of London’s architecture through the eyes of artists. The earliest work dates to 1616 and the latest 2019. There are nearly 80 works by over 60 artists, so the types of artworks on view are wide-ranging, to say the least.

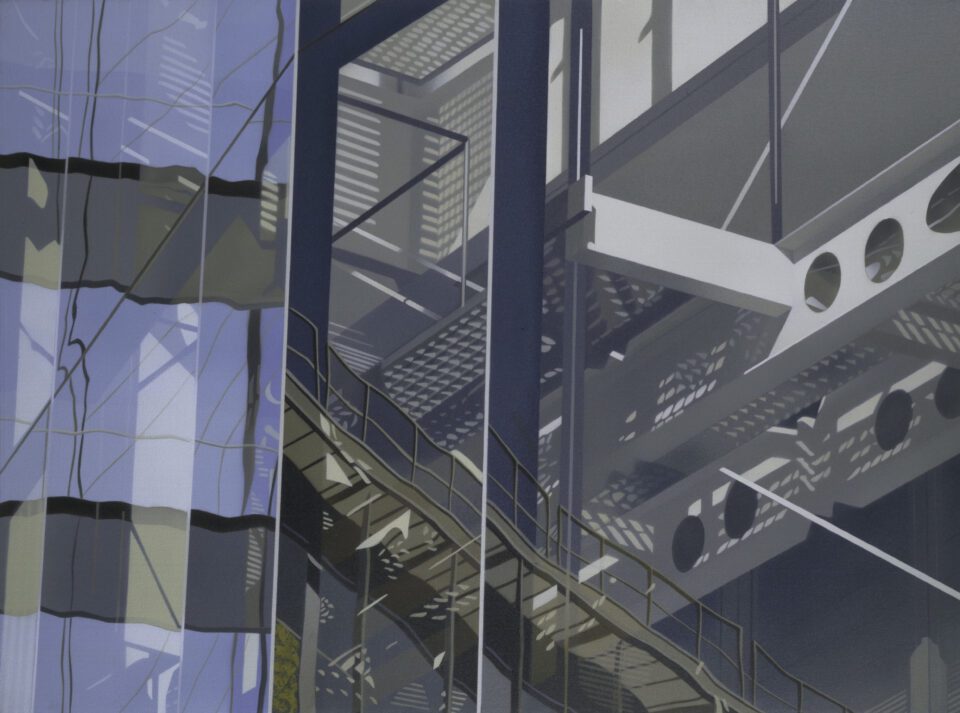

The works range from vistas to architectural close-ups, tower blocks to suburban homes, from impressionistic and modernist to hyperrealist styles, and from renowned artists, such as Canaletto, Frank Auerbach, Rachel Whiteread and Catherine Yass, to those who are less well known. Put simply, the extensive range of artworks is a reflection of the assortment of London’s architecture.

A: What are your highlights from the show?

ES: Old Saint Paul’s Diptych, 1616, by John Gipkyn is a quirky piece and one of the earliest British paintings of a historic monument. It is also a rare, but modified, view of Jacobean London before the Great Fire. Uzo Egonu’s Tower Bridge, 1969, is a wonderful example of the city in Egonu’s unique style; drawing on European modern art and the traditions of West African art to reinterpret London. Last Stand, 2019 by Catherine Yass is another highlight – I travel through Nine Elms (the subject of the film) every day and have seen the major redevelopment of the area over several years. This is what is now coming to define London, although I think (and hope) it will be short-lived.

Wasteground with Houses, Paddington, 1970-1972, by Lucien Freud is a highly personal and intimate work. His father, Ernst, died in April 1970. He had been an architect, and it’s significant that, during this period of grieving, Freud became increasingly fascinated with terraced houses and factories, painting a small group of London townscapes between 1970 and 1972. Finally, Albany Flats, by David Hepher, created from 1977-1979. Tower blocks and council housing have been the subject of Hepher’s paintings for over 40 years. Although there are no figures the work is completely full of human presence through the range of curtains and ornaments depicted in each of the windows.

A: Architecture of London demonstrates the city’s continuous transformation. What does the collection say about the future of the city?

ES: I think it says that the look and feel of the city will continue to change. We can’t necessarily predict how the cityscape will look 10, 20, 50, or 100 years down the line, or what factors will influence these changes. What I do know is that artists will continue to be influenced by London’s buildings, whether it’s their construction and demolition, as a memorial or a protest.

A: What do you hope audiences take away from the show?

ES: Many visitors have said that they come away feeling uplifted, with a sense of optimism and hope. I couldn’t have wished for a better response.

The exhibition runs until 1 December. Find out more here.

Lead image: Market Arcade, Ben Johnson, 1986, Ben Johnson.