New works by the influential artist Isa Genzken challenge the dominant norms of gender and scale within sculpture in a new show at Hauser & Wirth, London.

In an interview in 2003 for Camera Austria, the acclaimed Berlin-based multimedia artist and sculptor Isa Genzken contemplated the philosophical approach that has underscored her vast practice for more than 30 years: “You’ve got to put yourself in the viewer’s shoes when you do something. That’s important to me. It may be complicated, but it’s important to me. Otherwise I find it too cold or too arrogant.” Genzken’s rationale is a testament to her need to communicate the “real world”, and there is an instinctive desire to connect contemporary art within the context of reality. She states: “It must have a certain relation to reality. I mean, not airy-fairy, let alone fabricated, so aloof and polite.” Clearly this viewpoint is inherent in the aesthetics of the everyday materials and objects that the artist chooses to work with when composing a sculpture, installation, collage, photograph or video. In an article from 2006 for a show at Galerie im Taxispalais, Innsbruck, the critical writer Petra Löffler said: “The artist does this with an almost eerily precise eye for the mixtures – that make up our modern world – everything she observes is here and now.”

With a retrospective planned at MoMA in 2013, this exhibition at Hauser & Wirth’s Savile Row gallery in London reiterates Genzken’s significant presence within the contemporary art world. Florian Berktold, Director of Hauser & Wirth Zurich, asserts: “With the upcoming retrospective in New York, it will become even more evident that she is one of the most important contemporary sculptors; a stereotypically male-dominated medium. This speaks volumes of her determination, persistence and creativity.” It is a determination that has served to maintain Genzken’s artistic career over several decades. The current exhibition brings together a number of works realised in the last two years, some of which were shown earlier in 2012 at Hauser & Wirth Zurich and at the Schinkel Pavillon in Berlin. As an influential, relevant catalyst, one can certainly recognise the impact that her works may have had on international artists such as Urs Fischer, Cathy Wilkes and Thomas Hirschhorn, and the regional artists Maria McKinney, Willie Herrón, Nevan Lahart and Mark Durkan amongst others. Genzken’s own influences include Bruce Nauman, Sol LeWitt, Carl Andre and even more pertinently, Modernist architecture, minimalist design, pop culture and the kitsch. Berktold enthuses: “Genzken has a unique and inimitable visual language as a sculptor. She is inspired by a host of different sources – Genzken brings all of these aspects together to create a practice that is continuously looking around itself, translating experience into a three dimensional form.”

The skyscraper as a totemic effigy has seduced and fascinated the artist for a number of years. In conversation with Wolfgang Tillmans in Camera Austria, Genzken explains: “New York is a city of incredible stability and solidity. And then the height of the buildings – that impressed me. When I came back to Germany it seemed to me that it wasn’t particularly nice, my visual surroundings – it was all so dreary. New York just has an incredible sense of quality.” This appreciation of verticality became a regular point of reference. In works from 1998, the artist presented four aluminium photographs simply titled New York Skyscrapers. Genzken arranged the composition of the images meticulously in a precise linear formation, thus reflecting the minimal design of the subjects themselves. New York provides Genzken with unlimited inspiration, she said: “To me, New York has a direct link with sculpture.”

This alliance with New York can also be witnessed in previous shows such as the 2008 Ground Zero, presented at Hauser & Wirth’s Piccadilly gallery. Genzken showed a new body of work (ironically in the American Room) that included architectural proposals for Ground Zero, the World Trade Center site now resonant with political significance. These proposals take the form of sculptural renditions of towers assembled from appropriated ready-mades. The artist consulted a specialist team of engineers to ensure that each maquette could be realised to the approximate scale of the Twin Towers. These scaled works place the artist and the viewer tangibly on a relatable level in relation to the connotations this site now holds. Rather than restating the power of commerce, Genzken’s imagined buildings are designated a social purpose – church, hospital, car park, nightclub – becoming places to participate in community as opposed to purely utilitarian office blocks. The artist places her stacked collections on trolleys or cabinets with castors. The movable nature of the works adds a sense of impermanence, emphasising the transitory nature of all things material.

Several of the sculptural works contained within the present exhibition at Hauser & Wirth are composed of brightly coloured modernist designer chairs, colour prints, Perspex sheets, cartoon figures, toys, fabric, glass and mirror foil. The Philippe Starck Louis Ghost Chair becomes an invariable aesthetic reference, serving in a majority of the works presented. The design itself is a pastiche of a traditional ornate armchair from The Palace of Versailles; simplified in shape and form, it is understandable how the object’s minimalist postmodern aesthetics would appeal to Genzken. By placing them on top of one another, the artist’s treatment of the objects removes them from their context as functional items. The Perspex chairs are left to teeter precariously on top of shiny mirrored or brightly coloured cabinets that serve as plinths. The subsequent “building” is not only imposing in height but is also not very secure. Notoriously, the structures are rarely held together properly, sometimes only fastened with strips of gaffe tape or thin layers of glue. This is intentional; quite simply Genzken prefers the sculptures to remain on a point of instability and on the verge of collapsing. Perched on the upended chairs, the artist props small toys, masks and Disney cartoon figurines playfully. The critical writer Petra Löffler asserts that this is “one of those unexpected combinations Isa Genzken capitalises on artistically.” As a whole, the works seem to represent an emblematic totemic monument; a framework of assemblages layered and juxtaposed, rising in an acrobatic tension of balance and flux. Löffler suggests that Genzken “plays ping-pong with the unreasonable demands of the world in which we live.” Here we are reminded of the dualities of the human condition. Genzken’s “real world” is in an unreliable and fluctuating state. Löffler contemplates this approach: “Genzken, however, rejects this kind of architecture of power, just as she abhors monumental sculpture. Her predilection for transparent or reflective, yet also commonplace, materials, which can be easily joined together with adhesive tape or silicon, disregards the actual built monumental monotony of Berlin with a wonderful lightness of touch. At the same time, it fends off the dominant artistic tradition of equally weighty sculpture.”

The monumental, or the paradox of the anti-monumental, forms a repeated narrative throughout a number of images and sculptures contained within the current exhibition. In a series of floor pieces, the extended vertical form is referenced diagrammatically in two-dimensional photomontages placed on the horizontal. Untitled 2012 collates prints, wallpaper, wrapping paper and colour photographs under a “glass ceiling.” The collected artefacts are mostly elements of publicity material derived from Genzken’s previous exhibitions. The structure echoes formal components of minimalism’s floor-based works such as those by Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt. By placing the publicised history of her art practice within this format, Genzken credits these artists’ influence but ensures her own personal engagement with minimalism is evidenced. In a conversation with New Zealand artist Simon Denny in 2009, Genzken said:“I was trying to get this balance between minimalism and something else beyond that – in dialogue with minimalism, but with content. That was always the thing with minimalism; there was no content allowed, of course, but only the thing in the space. That was what Sol LeWitt was always about, and Carl Andre – it was all about avoiding content.”

In other untitled works, the same format is repeated, and the content of the assembled images refers directly to particular works such as Wind (2009). Within one horizontal arrangement, a reproduction of a Da Vinci portrait is placed above close-ups of people’s ears photographed by Genzken in New York. Lying below these are photographs of Michael Jackson taken by Annie Leibovitz, with a copyright logo on each. Löffler points out that Genzken is “equal to international politics and private agony; to the trauma and amnesia that have become hallmarks of our contemporary world.” The artist possesses a genuine admiration for Jackson’s showmanship as an iconic performer and a universally recognised public figure. Talking with Simon Denny, Genzken explained: “The thing with Michael Jackson is that it is all far away – there is this distance to the whole. He is completely unattainable.” The combination of these varied images leads to a confluence of associative questioning. Outside of the artist’s selection process is there a connecting thread that ties these references to one another? Löffler stated: “Anyone who seeks to identify the objects, situations or actions depicted to satisfy their interpretative urges will find that Genzken leads them astray.” When Duchamp initiated the ready-made, he did so in an attempt to question the very foundation of artistic tradition. Today, the ready-made has become part of that tradition and is used by artists for a range of purposes. While Duchamp set a strict non-rational set of rules for selecting his ready-mades, such as imposing a random time of day or weight ratio as the deciding factor to guide choice, Genzken’s decisions seem driven by personal fascination. Materially, there is a predilection for lacquered wood, designer chairs, shiny surfaces, wooden crates, plastics and Disney memorabilia. Löffler determines that “in the process [Genzken] grasps structural links between the private and the political in a thoroughly shocking manner.”

Collecting and assembling are also evident in wall-based works. Reminiscent of Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines, the works collate images, materials and actions into one coherent construct. Speaking of his incorporation of found objects into his work in an interview with Rosetta Brooks, Rauschenberg stated that he “wanted something other than what I could make myself and to use the surprise and the collectiveness and the generosity of finding surprises. And if it wasn’t a surprise at first, by the time I got through with it, it was. So the object itself was changed by its context and therefore it became a new thing.” This transmutation of meaning through proximity would appear to be implied in Genzken’s choice to repeat certain images within the one piece or incorporate one image in several separate pieces.

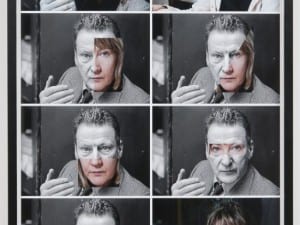

Cultural influences and historical symbolism are addressed in the formally arranged Nofretete (2012). Reproductions of the Ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertiti’s famous bust are placed on a row of pedestals that have been designed to follow a sweeping curve. According to Berktold, the arrangement of the pedestals echoes “her hyperbola sculptures from the late 1970s.” The artist renders each of the heads contemporary with different designer brands of sunglasses. On the ground, at the foot of each pedestal, Genzken has placed a reproduction of the Mona Lisa upon which she has superimposed her own features. The portrait of the artist is woven into the composition and very framework of the artwork itself. Berktold reflects: “With Nofretete, Isa inserts herself playfully into an exploration of the place of women in art history.” The artist places herself within the context of these celebrated iconic figures, and in doing so, Genzken claims ownership through association. These portraits establish a historical link between all three women. Does Genzken wish to share the same recognition and longevity? When the question “where would you place Genzken’s work in relation to the contemporary art market?” was asked, Berktold responded pertinently: “In comparison to male artists, her work is still undervalued given her long career and rock-solid institutional support.” By incorporating herself within her work and the contexts she creates, Genzken invites visitors to consider the place of the female artist within the contemporary art world.

Isa Genzken ran until 12 January 2013 at Hauser & Wirth London, Savile Row. For further information visit www.hauserwirth.com.

Angela Darby