Joaquín Torres García (1874-1949) is slowly but surely claiming his place as not only one of the godfathers of Latin American Modernism, but as a universal modern master whose work deserves to rank alongside the key figures of 20th century art. The last step in this direction was the recent MoMA retrospective devoted to the artist’s vast and diverse career. The exhibition travelled to Madrid’s Fundación Telefónica and has been on show there throughout the summer. Only a week after its closure, a much smaller but equally impressive show of his work opened in the city.

The gallery directed by Guillermo de Osma, where the new exhibition is being held, is arguably one of the places where Joaquín Torres-García is most appreciated outside his native Uruguay. The gallery has dedicated several exhibitions to the artist and owns a splendid collection of his work that spans his tremendously varied output. The fact that it is a small exhibition, where different techniques and periods coexist, plays to the advantage of the great complexity and contradictions that oversaw the Uruguayan’s life and work.

Torres-García began his career in Barcelona, where he moved with his family from his native Montevideo. The city proved central to his artistic sensibility. It was a cultural hotspot and the centre of Catalonia’s national awakening. Along with other artists, Torres-García began to strive for the creation of a kind of “national style”, which received the name of Noucentisme. It drew from Antiquity in both form and content and received the support of the authorities, who commissioned Torres-García a series of mural paintings for the Catalan parliament. With a shift in power, though, this official support came to a halt and the commission was suspended. This coincided with Torres-García’s discovery of the avant-garde, as he was able to see the work of several European artists who had taken refuge in Barcelona during the First World War.

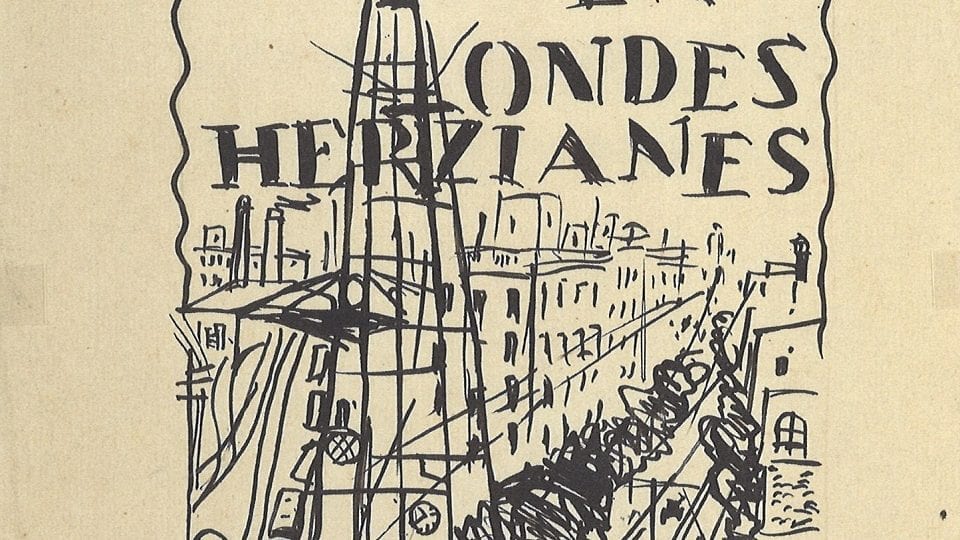

Before leaving for Paris in the early 1920s, Torres began to turn to new subjects. His paintings and drawings embraced the teachings of Cubism in order to create powerful urban landscapes, perfectly capturing the speed and bustle of the modern city. His interest in this subject deepened during his move to New York, where he lived briefly before returning to Europe. All the while, Torres developed a parallel activity in applied arts, most remarkable among which are his toys, which he initially made for his children but later began to commercialise. This particular venture was guided by new ideas in education he had learned about and by his interest in how art could have a direct influence on society. His commercial activity in no way compromised his aesthetic investigations, which by the 1930s were moving towards Constructivism. His unique version of this style would fully develop after his return to Uruguay in 1934, where he would die fifteen years later.

Thus far, we find ourselves with a typical modern artist biography: initial figurative style – discovery of the avant-garde – experimentation – mature style based on that experimentation. But to accept this view of a perfect progression towards a predestined end, as academic historiography would have it, would be to miss the rich complexity of Torres-García’s oeuvre. Because the truth is that he never did completely abandon his initial interest in Antiquity, and throughout his whole life he shifted between that early style and his more evidently-modern Constructivism. Skimming through a complete catalogue of his work, we will find serene classical compositions painted at the very same time of his noisy cityscapes. While his career moved towards new boundaries, he always kept one eye on the past.

Torres also stands out for his unique position in the midst of the heated artistic debates of interwar Europe. In the aesthetic confrontation between analytical abstraction and Surrealism, Torres chose the former, yet he was soon to distance himself from the orthodoxy imposed by De Stijl, which he was initially close to. We could say he was just as allergic to academic naturalism as he was to strict abstraction: his embrace of geometry did not mean perfectly straight lines, nor did ‘abstraction’ stand for the complete banishment of the figure in painting. Placed between extremes, Torres chose to stand somewhere in the middle.

It was only natural, therefore, for him to formulate his particular aesthetic credo. A prolific writer, Constructive Universalism, published in 1944, is the culmination of Torres-García’s ideal definition of art. Influenced by his lifelong bonds with Antiquity and neo-Platonic thought, his art sought to be universal and timeless. As José Ignacio Abeijón points out in a text that accompanies the catalogue, Torres’ idea of abstraction, which he always defended, was a peculiar one. As opposed to Van Doesburg or Mondrian, who stripped nature bare in order to reveal its elemental structure, Torres-García begins with abstraction and ends in nature: ‘We must not start from nature to reach abstraction, but from the abstraction in geometry and colour in order to reach reality,’ he wrote in 1930. One need only observe the beautiful Constructive with Four Figures, on show at the current exhibition, to understand what he meant.

Rubén Cervantes Garrido

Torres-García: Art and Design runs at Guillermo de Osma Galería, Calle Claudio Coello, 4, Until 11 November.

Credits:

1. Joaquín Torres-García, Poemes en ondes hertzianes (1919), Ink on paper, 32 x 22 cm.