A collision of the traditional and the contemporary is currently being presented at Bradford 1 Gallery. It would seem that Street Art, which has moved on from the painted wall to print-making, has evolved into a resonant and democratic medium of expression and reflection. Certainly here, traditional as well as popular images and modes of communication are subverted, and often with irony. Comment is made on current events and contemporary life. But does the presentation of the Street Art in a gallery, away from direct interaction with the urban environment itself, rob it of greater democratic resonance? No: this would be the knee-jerk reaction. It is an evolving medium; and objections against this mode of presentation might be countered with an accusation of false notions of aesthetic authenticity. Also, it is a publicly funded gallery and there is no admission fee. Furthermore, the work exhibited has been collected from all over the world, and the viewer would be hard pressed to view work by all of the artists included on the actual street. The V&A has been collecting such work since 2004. This selection is divided into four sections. Rather appropriately, each section has its own wall.

The first section is titled: “Politics and Propaganda”. Most striking is Banksy’s piece, Napalm (2004). Here, the famous and alarming image of the napalm-scorched,Vietnamese girl-child in flight has been taken from the original photograph. She is flanked by two taller figures who apparently hold her hands in the manner of parents. They are, however, on one side, Ronald McDonald; and on the other, Mickey Mouse. The style in which the whole image is printed – black and white, with a sort of Lichtensteinian dot print impression – lends convincing homogeneity. This effect also induces a double-take in the viewer, followed by nausea. The figures of children’s entertainment are imbued with an insidious sense of Imperialistic hypocrisy by association with the victim. The year provides the anti-American political context of recent memory. Well-known images here are subverted with great impact because of the initial impression of innocence. A similar strategy is used in the case of Sargent Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Bastards (2008), by Pure Evil. At first glance, The Beatles’ album cover of the title from which this is derived is presented. On closer inspection, the crowd of figures who, on the original album cover form a collection of The Beatles’ influences, is in fact populated by extremist dictators and controversial politicians. These “Bastards” are rendered somewhat human by their inclusion in the “Lonely Hearts Club.” This coupled with the bluntness of the title can be felt to elicit a post-Jungian guffaw.

The second section is titled: “Symbols and Characters”. Here, examples are exhibited of work in which the artists include their own identifying symbol, much like a graffiti tag. Three prints by Shepard Fairey ironically subvert his own signature symbol – the face of wrestler, Andre The Giant – with the evocation of both Soviet propagandist symbolism and American corporate advertising. This seems to capture the tension between collectivism and individualism, and the related issue of creative authorship and its emphasis in the West. This sense is particularly strong, for the claustrophobia aroused in the efficacy of the execution, in the work, Old School Posters (2001). In the same section, two prints by Miss Tic are noteworthy for the elegance of the style – she seems to use stencils. They are titled: Nous sommes tous en situation irrégulière (2004), and, A Ma Zone (2004).

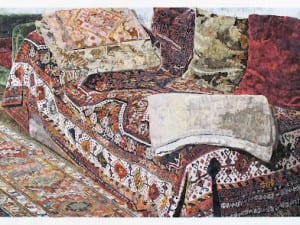

“Influences and Image-making” is the title of section three. Themes from Art History are employed here along with humourous versions of existing images. There are elements of portraiture, contemporary Surrealism and Art Nouveau. The human skull as memento mori is much used. In Kerry Roper’s Time Waits for No Man (2010), we find the cradle and the grave bluntly juxtaposed. The Reaper himself adorns a baby’s head, starkly contrasting the infantile sweetness with skeletal severity. Also displayed in this section are two folded books by Jon Burgerman, which seem to reference in microcosm with equal parity the ancient mural and the urban, graffiti-covered wall. The books please the eye for the balance and intricacy of the detail.

As though to rebuff any accusation of inauthenticity by exhibition, section four brings the urban environment indoors as a subject in its own right. It is titled: “City and Street”. Homage is paid to the street itself in Yello Sao Paulo, by Projeto Che. Here the an urban thoroughfare is enriched with the use of bright yellow and treated with mesmerising geometrical symmetry, incorporating a mandala. In this way, the street as subject is given a cathedral-like grandiosity.

Street Art: Contemporary Prints from the V&A, 24-03-2012 until 09-06-2012, Bradford 1 Gallery, Centenary Square, Bradford, BD1 1SD. www.bradfordmuseums.org

Aesthetica spoke to Broken Fingaz Crew, a pioneering street art collective from Haifa, Israel last month. Read the full interview here.

Credits:

Kerry Roper: Modern Youth 2010 © Kerry Roper. Courtesy of Kerry Roper

Text: Daniel Potts