Schwitters in Britain is a compelling exhibition because it charts the artist’s interest in ephemera, as well as the formal investigations of figuration and abstraction, painting and assemblage that preoccupied his work. Through these two outlets, we learn the importance of “place” in Schwitters’ practice. Following his inclusion in the Entartete Kunst exhibition in 1937 of “degenerate” art, Schwitters’ exile from Nazi Germany to Norway and then to Britain from 1940 gave him exposure to a new sense of place.

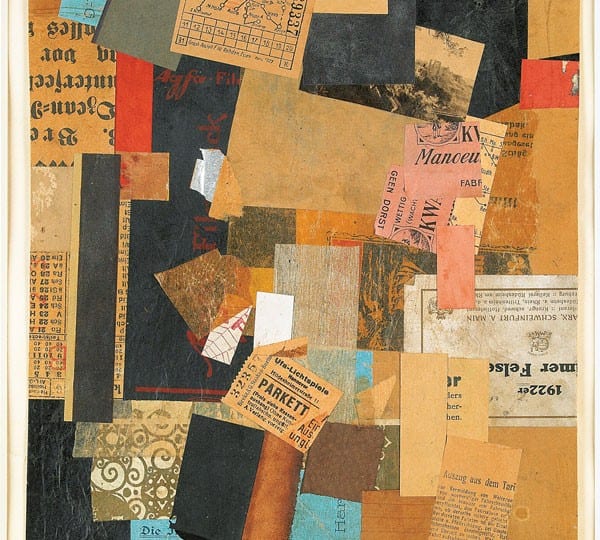

The importance of place also impacted on the artist’s use of materials. The lingua franca of the German avant-garde in the 1930s was assemblage, a bi-product of the 1920s German revolutionary photomontage. Assemblage became the visual experience of the artist’s everyday life, which is now understood through the objects he appropriated into his artworks. The Quality Street/Basset sweet wrappers and London bus tickets in Untitled (Quality Street) 1943, is an English treat for the British gallery’s audience.

Schwitters had an interest in pop culture and in the typography of advertising, seen in En Morn 1947, which is also understood through letters to his son and to the artist Moholy-Nagy. These not only make for interesting archival material as a pause to the show, but also help engage the visitor to understand the contemporaneous nature of the objects, and the socio-economic aspirations of war-stricken Britain. Through the use of every day artefacts we learn about Schwitters’ situation as an émigré artist, whose artworks are informed by his geographical situation in Britain, though his abstract style remains true to his German Dada heirs.

Merz, defined by the artist as “the combination, for artistic purposes of all conceivable materials” is well explained in the exhibition. The curators have dedicated one room to a series of slides that help the visitor discover the immersive nature of the Merzbau – the architectural installation that took over 6 rooms of his Hannover house before it was destroyed in WWII. From the Merz concept we can see Schwitters’ long lasting influence on British artists after his death. Obvious examples include Adam Chodzko and Laure Prouvost, whose contemporary responses to the Merz Barn of 1947 in the Lake District appear at the end of the exhibition in Because… and Wantee respectively, and Mike Nelson’s architectural installation for the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennial 2011.

When Schwitters described the work he produced in England as the “best things [of the moment] are my small sculptures”, the size of these works is important here. These small scale investigations into sculptural space are powerfully intimate, and Untitled (Togetherness) 1945-47 engrosses the viewer in the sculptural relationship between two abstract forms.

The idea of place serendipitously fits into the exhibition when we consider that Schwitters’ first arrival in Britain was at Leith, the same district of Edinburgh where Eduardo Paolozzi grew up, and who would later be inspired by Schwitters. If Paolozzi is known as the father of Pop Art, as seen in this exhibition at Tate Britain, then Schwitters is arguably the grandfather.

Schwitters in Britain, Until 12 May 2013, Tate Britain, Millbank, London, SW1P 4RG, United Kingdom

Asana Greenstreet

Credits

1. Kurt Schwitters, doremifasolasido c.1930, Private collection.

2. Kurt Schwitters, Merz Picture 46 A. The Skittle Picture 1921 , Sprengel Museum Hannover / DACS 2012.

3. Untitled (Quality Street) 1943, Kurt und Ernst Schwitters Stiftung, Hannover, Sprengel Museum Hannover and DACS 2012.