The brightly coloured and minimally drawn paintings of everyday objects in Michael Craig-Martin’s current exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery are nothing we haven’t seen before in Warhol, Caulfield, or others. But then this is largely the point. It is our familiarity with these objects, seen through the changing lens of culture and time, which gives a sense of their present or looming obsolescence: their transience.

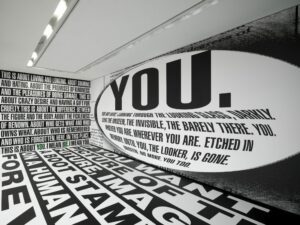

Irish born, American raised and London based, Craig-Martin began his career in the 1960s exploring the conceptual limits of contemporary art and the boundaries between functional and functionless forms. While much of his early work focused on sculpture, the majority of pieces in Transience – his first solo exhibition in a London public institution since 1989 – are two-dimensional. Among the predominant paintings there are also two pieces made in tape on the space’s walls, wallpaper designed especially for the exhibition, and, exceptionally, a sculpture outside in Kensington Gardens.

The works adhere to common criteria in their production. Their style, the thickness of their lines, and the proportion of subject to canvas are largely standardised, meaning it is our experience of the objects represented and their place in time that lend them significance. In this sense it is appealing to think of the taxonomy of everyday objects here as an exercise in both history and historiography. Those changes which do occur over the years are reflective of developments in technology and production themselves. As Marshall McLuhan writes in Understanding Media, which had a strong influence on Craig-Martin’s thought: “technical change alters not only habits of life, but patterns of thought and valuation.”

One of the most interesting things to note in Transience is the change in how much information is necessary to depict increasingly sophisticated inventions. In works from the 1980s and early 2000s items are often grouped together, both their titles and forms reflecting a superabundance of function. In Eye of the Storm (2003) and Biding Time (2004), with their collections of analogue objects (fans, briefcases, cassettes, pitchforks, metronomes), each linear representation also implies a purpose. Notably, the functional forms of these earlier subjects necessitate their being drawn as isometric projections, and this continues into the early 2000s with Cassette (2002), Flashlight (2002), and Palm “Tungsten” T-Handheld (2003). In much of the later work on display, however, the drawings are frontal. Doing away with any illusory appeal to three-dimensionality they reflect the rupture between function and form, with the sheer number of later paintings commenting on the acceleration of this process.

Certain objects still flaunt and require references to their functionality but, as they become more familiar, these indices disappear. 2003’s Apple 17inch PowerBook G4 is drawn isometrically, its keys emphasised in bright colours, whereas a similar object in 2014 needs no such qualification. The clearly identifiable Macbook in Untitled (laptop turquoise) (2014) is drawn frontally, and there is even a third phase to the process, where only a fragmented image of a laptop in Untitled (laptop fragment) (2015) provides sufficient information for it to be recognisable.

The conclusions seem to be that branding has become a function in itself, that the least aesthetically interesting images are conceptually the most, and that at the compositional heart of many of Craig-Martin’s most recent subjects – the laptops and iPhones – is the screen. These monochromatic rectangles have something of the depth and unsettling effect of Malevich’s Black Square. They collect and conceal innumerable functions in a form that follows none, while swelling with a sense of potential that far outstrips our ability as users to fully exploit them.

As screens force themselves into the centre of these works and of our lives, absorbing and abstracting their predecessors’ uses, it is hard to say how Craig-Martin’s inquiry into form and function might continue. But then, for the attentive viewer of paintings from the early 2000s grouped in the Serpentine’s North Gallery, there is a reassuring incongruity. As if to remind us that design can be cyclical, that some old objects can be fragmented but still recognised, archaic but still desired, there is one much more recent addition: a fragment painting of a perfectly functional, perfectly formed, analogue wristwatch [Untitled (watch fragment) (2015)].

Ned Carter Miles

Michael Craig-Martin: Transience, until 14 February, Serpentine Gallery, Kensington Gardens, London W2 3XA.

For more information, visit www.serpentinegalleries.org.

Follow us on Twitter @AestheticaMag for the latest news in contemporary art and culture.

Credits

1. Michael Craig-Martin: Transience installation view, 2015. Courtesy of Serpentine Gallery.