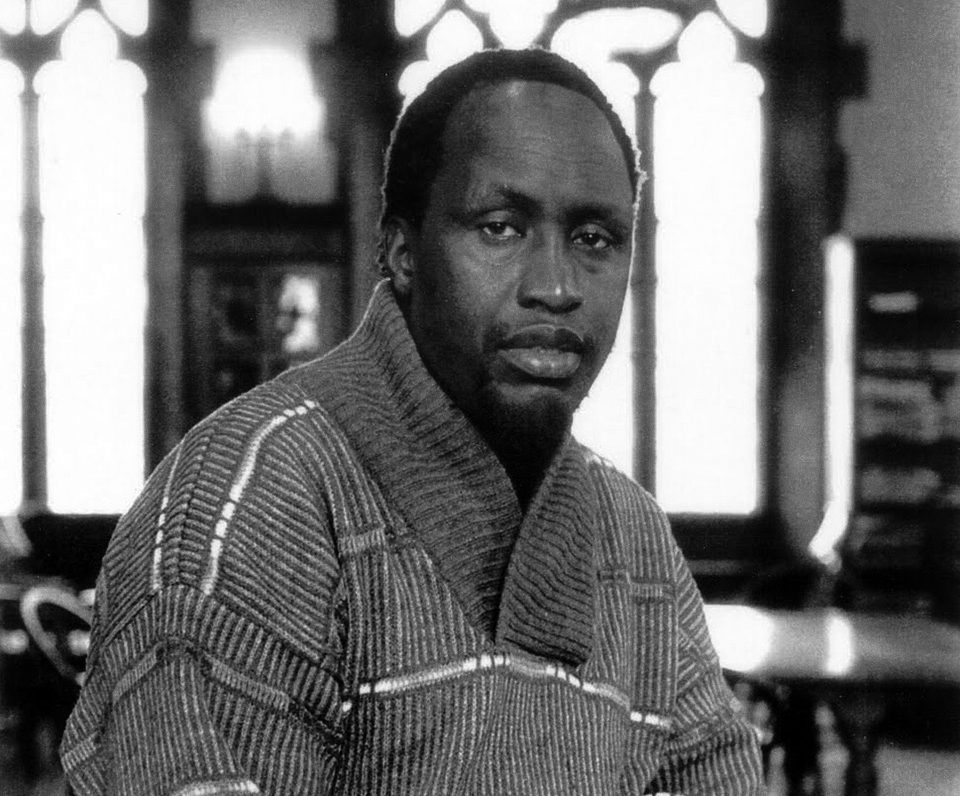

One of the forerunners of African literature and most widely read African authors of our time, Ngugi wa Thiong’o was born in colonial Kenya during World War Two and is the author of several novels, plays, and non-fiction pieces, which tackle issues of colonialism and postcolonialism.

Ngugi’s latest novel The Wizard of The Crow, in his own words, is nothing less than an attempt “to sum up Africa of the twentieth century in the context of 2,000 years of world history.”

The novel begins in the present time and is set in the “Free Republic of Aburiria”. The Wizard of the Crow dramatises the corruption and power struggles between the dictator-state and the people. The story unfolds through a tale of a young educated man in search of a job. His quest for work turns into something far more revealing, as he struggles against losing hope. From this the Wizard of the Crow is born and becomes a saviour to all.

Throughout the novel there is corruption and despair. The Ruler has absolute power,and his birthday gift is an idea called Marching To Heaven, in which Aburiria will build the steps to heaven, of course with the help of the Global Bank, who in the end refuse to support the idea because of the country’s unrest and political instability. This sparks off the queuing mania, in which the citizens of Aburiria begin queuing for jobs, change and hope. This queuing mania is representative of many truths of modern history.

After a diplomatic visit to the US, The Ruler contracts a strange malady of words, which has also affected other characters in the book. The Wizard of The Crow is sent to cure The Ruler’s aliment.

The nature of The Wizard of The Crow is that of someone who is genuine and far removed from corruption, this often leaves the Wizard feeling isolated. He is only consoled by his companion Nyawira, who is a leader in the Movement For The Voice of The People. She is an archetypal modern woman, with many admirable convictions, the most poignant being freedom.

The novel uses humour and revelation to underscore its powerful meaning. Ngugi wa’ Thiong’o has written a compelling novel, which will fissure the truths that fiction holds. The satire is ripe; The Wizard of The Crow is a first class masterpiece.

Can you tell me a bit about yourself?

I was born in Limuru, Kenya, in 1938 into a colonial situation, as Kenya was a British settler colony. The period of my birth to early childhood was also that of the Second World War and the explosion the atomic bomb in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Mau Mau war of independence started in 1952 culminating in Kenya’s independence in 1963. I mention the two events because they dominated my childhood, and my education.

When and why did you begin writing?

I have always been interested in story telling, listening mostly, and it was this that led me into books and then writing. I started writing when I was an undergraduate at Makerere University College, then an affiliate of the University of London, in 1960. The River Between was my first effort at novel writing; then Weep Not, Child. Weep Not, Child however was the first to be released by Heinemann in 1964, followed by The River Between in 1965.

What do you see as the main power of literature?

Literature is part of the aesthetic system of a community. It creates powerful images of the world. These images are important for the imaginative development of a people, both individually and collectively.

Since writing Weep Not, Child, how do you feel that the genre of postcolonial literature has developed?

Weep Not, Child, and many of the novels written by African writers of my generation, tended to follow what I might call the Victorian realism of the English novel. This is because a good number of us were products of the English departments and the literature to which we were then exposed. Among these exposures was of course the English novel. But the novel, as a genre, is changing with writers, particularly those from Africa, Asia and Latin America, finding inspiration from Orature, the oral and the aural inheritance of the peasantry. This releases the imagination from the constraints of narrow realism.

For you, what has been the one single most important aspect of your career?

The most important aspect of my career was my change from writing in English to writing in Gikuyu.

What’s your favourite book and why?

My favourite book is the novel I have yet to write. I have no idea what that novel is, but I am always striving to write it. The novels I have already published were all attempts at writing that novel.

What’s been the best thing that has ever happened to you?

The best thing that has happened to me was the rediscovery of my language.

How would you describe the transition in literature from colonialism to post colonialism?

The main change from the colonial to the postcolonial has been the writers’ discovery of the magic of the oral tradition.

Do you think that European/North American writers have been influenced by this genre?

The magic realism of that rediscovery and reconnection with orature has affected literature worldwide.

Can you tell me more about your choice to write in Gikuyu?

African languages have been dominated by those from Europe. Most Africans, the majority, speak African languages. My choice of Gikuyu was my attempt to do for my language what all writers and intellectuals the world over have done for their languages. What is possible in Gikuyu is equally possible in all the other African languages.

In Wizard of the Crow, when The Ruler receives the present of Marching to Heaven, can you tell me about the deeper meaning of that gift?

Wizard of the Crow deals with, among other things, a third world dictatorship that was often sponsored by Western democracies. Western democracies, particularly during the Cold War, were always quite happy to gather the fruits of dictatorships in Africa and Asia and Latin America. These dictators often saw themselves as emissaries of the West and God. They saw themselves as representatives of God on earth, hence the image of Marching to Heaven.

In Wizard of the Crow, can you explain what the never-ending queues represent?

I don’t really know. It is an image that imposed itself on me, and it came to dominate the narrative. But have queues and queuing for food, or jobs, or simply forced queuing, in colonial and postcolonial dictatorships not been the story of our times?

There are several points in the novel when you comment on identity and perceptions of meaning, when we are introduced to Nyawira, she used to call herself Grace, what wider meaning does this have for identity?

About identity and perceptions of meaning! Wizard of the Crow is inspired and influenced by the trickster aesthetics of the oral narrative in Africa. The trickster is a recurring character in African orature, the best known being Anansi in West Africa and Hare in East Africa. You may not know

what you think you know! One of the internal narrators in Wizard of the Crow is Arigaigai Gathere or AG, and he has no problem in colouring his narrations in his attempts to express an elusive meaning of what has happened.

What do you feel is the most pressing global issue at the moment and why?

In my view the most pressing problem is that of nuclearized nations. Between America, Western Europe, Russia, and China, they can blow the world into nothingness hundreds of times over. Nuclear disarmament for ALL nations (not for some) and the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons are the pressing issues of our time. But no less pressing is the increasing gap between the wealth of a few nations, mostly Euro-America, and the poverty of many nations, mostly Asian, African and Latin American. But in ALL nations, the gap between the rich minority and the poor majority is widening. This is the essence of globalisation and it is one of the central themes in Wizard of the Crow.

What are your plans for the future?

I want to write that novel I have always striven to write.