Designer Hussein Chalayan builds a new world on stage for Gravity Fatigue, combining fashion, architecture and dance at Sadler’s Wells.

Historically the relationship between dance and fashion has been weighted in one direction: the demands of the choreography have been the determining factor in the creation of costumes and selection of fabrics. Even the pointe shoe, which expanded the abilities of the dancers and the possibilities for choreography, was only developed after Charles Didelot (1767-1837) had made the idea of rising up en pointe fashionable through the use of wires in his ballet Flora and Zephyr (1815, Paris): the new design in footwear was a necessity to keep up with the needs of the dancers.

That is not to say that fashion has not impacted upon dance as well: Marc Happel of the New York City Ballet has spoken of the inspiration he has taken from Dior and Balenciaga in creating his costumes. However, the in uence of the fashion industry is usually upon the style of the clothing rather than the choreography itself. It is not often that the content of a dance routine is a ected by what the dancers are wearing, except perhaps in the case of an accidental loose ribbon… or a cape tied too tight (as evidenced by Madonna and Giorgio Armani). With this in mind, the decision made by Sadler’s Wells to invite acclaimed fashion designer Hussein Chalayan (b. 1970) not just to design but to create a whole new work for the theatre is both brilliant and astounding. The piece, Gravity Fatigue, reverses the usual relationship between the two art forms and it is the fabrics and the garments that here serve to determine the movements which are created.

“Normally the choreographer is approached to do a piece like this and someone like me would design the costumes but this time it’s the other way round. I was approached to be the author of it and Damien Jalet has been invited to the project to help us execute my ideas.” French-Belgian choreographer Damien Jalet is a keen collaborator who is skilled at making dance dialogue well with other art forms. He has previously worked with sculptors such as Jim Hodges and Antony Gormley as well as directors, musicians and other designers. For this particular work, Chalayan speaks about how the “garments act as the grammar for the piece” and how Jalet and his dancers had to interpret the ideas partially in response to the clothing. Many of the fashion pieces which have been created for Gravity Fatigue are constructed intentionally to have an impact on the choreography, featuring materials that can stretch or constrict, or bind two performers together. Some of them force the dancers into various positions and collaborations and there is a sense of joyful experimentation of the possibilities that are o ered by each garment.

It is clear that the clothing remains at the forefront of Chalayan’s interest and that this foray into dance is a way to “expand ideas much more deeply and to extend the life of the clothes in a different way.” Having dancers instead of models wear his items opened up untapped potential: while models are trained to move in a way that emphasises and highlights the garments, dancers have a different approach to movement. One of the most enjoyable parts of the process for Chalayan was watching how the dancers played with their outfits: “It’s an exercise in how you engage with the clothes in order to create compositions and how you engage with the space.” For a designer who has previously demonstrated a fascination with the functional and adaptable nature of fashion and with the manipulation of space, the introduction of dancers into his world is a fitting one. The two blend so well together not only because of the links between fashion and dance but because of the specific intellectual similarities that the two share with architecture. The idea of space as a key component of creation is inherent in both dance and in Hussein Chalayan’s fashion. Dancers create movement in space and build stories, images and ideas through the way they place themselves in their environment. In many ways they resemble architects, working with shape and form to create definition on stage. Likewise, Chalayan creates works that morph and change the space which they occupy, both altering and impacting upon the environment around them.

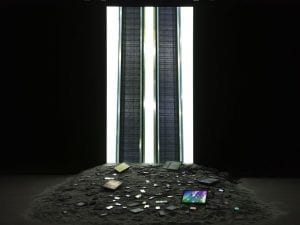

Perhaps the best example of this comes from his Afterwords collection, which was first showcased at Sadler’s Wells in 2000. In the exhibition, four chairs surround a table and the chairs are dressed in chair covers. The models approach the furniture and relieve the chairs of their furnishings, turning the chair covers into dresses. The table in the centre is then altered into yet another dress through a series of telescopic pieces that slide upwards when pulled – his notorious “table dress.” Both the models and the fashion pieces directly engage with, and form part of, their surroundings; they are responsible for, and influenced by, their environment. Other designs by Chalayan have taken the idea of construction rather more literally – in 2011 he built an “egg” around Lady Gaga for her to make her entrance at the Grammy Awards in, so that the singer might appear to “hatch” out of it on arrival.

Hussein Chalayan refers to his interest in the experience of space as forming a fundamental part of his approach: “In a way fashion designers are like architects because we play with creating a space around the body and architects create a bigger space around the body.” His relationship with dance then o ers yet another method of exploring this concept. In Gravity Fatigue, the dancers both interact with the wider stage environment and with the clothes that occupy the area more directly around them. The architecture that Chalayan and his dancers create is a fluid and ever-changing one; it is formed of movement and of space that is defined by how the dancers and the clothes work to create openings.

This idea of a moving architecture, of an environment that is created and then transformed, has an interesting correlation with the themes that Chalayan explores in his work and to his own life. Born in Nicosia, Cyprus, a city aggressively divided into two parts, Turkish and Greek, and having moved to the UK at the age of eight, Chalayan is intimate with the way a changing landscape can impact upon its people. Gravity Fatigue deals with these notions of displacement, migration and identity. The way in which fashion alters the dancers’ movements and forces them to shape their environment mimics the influence of architecture and environment upon the human state. The surroundings that are created and developed by people in transit or in flux are here expressed through the architecture of movement on the stage.

This co-production between Hussein Chalayan and Sadler’s Wells is a fantastic example of both the broad nature of contemporary dance and of Chalayan’s multi-disciplinary approach. By entering into a conversation with fashion and architecture, Damien Jalet and his dancers seamlessly adapt and expand to interpret and incorporate the ideas of both, which fits neatly into the aesthetic and intellectual implications of dance itself. A perfect collaboration of art.

Words Bryony Byrne

Sadler’s Wells, London. 28 – 31 October.