Arriving on the art scene in the 1970s, Linder Sterling (b. 1954) is known for her subversive collages combining the female figure with objects and nature. Currently exhibiting her first retrospective at Musée d’Art Moderne until 21 April, Sterling’s latest works will appear at the Hepworth Wakefield from 16 February until 12 May culminating in a living collage, The Ultimate Form, on 11 May. www.hepworthwakefield.org.

What was the starting point for your new piece, The Ultimate Form?

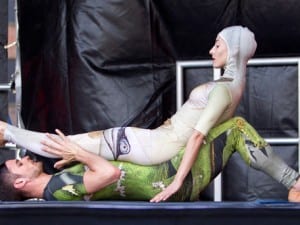

The Ultimate Form takes its name from one of Barbara Hepworth’s standing sculptures included in The Family of Man (1970) collection. Over the last few years, I have become increasingly fascinated by the life and work of Hepworth. Discovering her legacy at this point in my life has been both inspirational and daunting. It’s almost three decades after her death, so attempting to flesh out the artist, the woman and her life wasn’t easy. I actually found that it was her writing that holds the key to understanding her works. When she was asked how she wanted people to feel when they saw The Family of Man, Hepworth said: “With a sculpture you must walk round it, bend towards it, touch it, walk away from it.” I wanted to accept Hepworth’s invitation to do just that, and I decided to use dance. The Ultimate Form is a ballet that can exist in a very pared down and minimal state, or it can be reconfigured on a scale to equal the ambition of her Single Form (Memorial) (1961-1962).

How does it feel to present The Ultimate Form amongst Barbara Hepworth’s own works at the Hepworth Wakefield?

I feel like a prodigal daughter returning home. I want Hepworth to have her say too. We talk so much about the artist’s voice and yet rarely hear her. Hepworth’s voice is very sculptural – her language and tone are defined, and she uses pauses to pierce the form of her own grammar. Within the Hepworth Wakefield you will be able to hear her saying: “And the important thing each morning is to assess the day’s weather and to think about the light.” You will hear this as you wander through the artificial light emitted by back-lit retail display boxes, showing photographs of ballet dancers, eagles, hares and moths – anima, animus and animal, via Armani.

For this project you have collaborated with a variety of other artists including Kenneth Tindall of Northern Ballet, fashion designer Pam Hogg and Stuart McCallum, who wrote the score. How has their contribution added to your artistic vision?

All three collaborators share the ability to show a deeply empathetic response to the possibilities of The Ultimate Form. If Barbara Hepworth is the glue that we share, then we’re all happily stuck to each other for quite some time yet. All three fellow collaborators and the dancers from Northern Ballet understand the delicacy of the task ahead. None of us want to put our stamp all over Hepworth’s legacy; rather there is a lightness of touch from all involved, great respect and a focused playfulness. Each collaborator plays their part; we’re like a slightly dysfunctional The Family of Man.

Does performance art carry the same concerns as your previous work or does it focus on new interests?

The predominant difference with The Ultimate Form and previous performance works is that there is a complete absence of improvisation. The piece is scored and choreographed because I wanted precision and certainty in the work. In a way, it brings performance far closer to the technique of collage (cutting up magazines with a surgeon’s scalpel leaves little room for error). It’s also the first time that I won’t be participating within a performance piece; the “work” this time has been more about bringing the varied cast together and letting them take their places. Hepworth said that we all have aspirations that we share – “hopes for the future, belief in the future” – and that The Ultimate Form has “a kind of serenity saying ‘go on working, here I am.’” She left us a perfect template.

How have your collages changed over time?

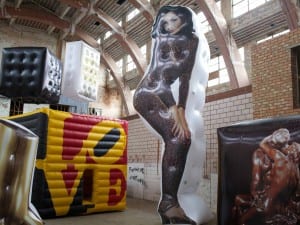

Some of my collages are now re-photographed and displayed in the kind of light boxes that you’d find in any department store advertising Dior or Armani. Size matters at times, whether it is performance work or collage, so having the ability to change scale comes in useful at times. In essence, though, very little has changed: I work with a very small palette of imagery and all my cuts are very precise. The work feels quite forensic; I always want to know everything about the creation of the images I work with. I never find any answers but I still ask the questions.

Your collages often unite humans and animals; is there a reason for this?

Maybe it is a longing to merge that which we deem as animal, both psychologically and ethically. I don’t eat animals and I try not to harm them. In using collage, I can explore the tensions between the human and animal condition. I can also play with ideas of coexistence; not in a cosy way, but in Tennyson’s sense: “Nature, red in tooth and claw.”