Jonny Briggs graduated from the Royal College of Art several years ago and has since gone on to feature in numerous solo and group exhibitions. An artist in search of his lost childhood, Briggs speaks to Aesthetica about the influence the RCA had on him and his perception of his artistic practice. This year the RCA graduate show runs 20 – 30 June across six different venues.

A: How has your time at the RCA shaped your artistic practice?

JB: When starting at the RCA I felt like a kid in a sweet shop with the facilities available there, which opened the door to realize new ideas in 3D scanning, 3D printing, milling, weaving, glass casting and darkroom printing. My peers and tutors Sarah Jones, Rut Blees Luxemburg, Olivier Richon, Peter Kennard and Hermione Wiltshire have been invaluable in encouraging the way I see and question my work, and theorists such as Alexander Düttmann and Darian Leader fed and rearranged my thinking in how I looked back at it.

Learning to communicate the ideas through writing my dissertation also helped to articulate what my interests were, and fuel the work in a more informed direction.

The result of the two-year course was more open, surprising and playful work, which was more coherent and thought provoking than previous pieces. I understood the motivations of my work more, and became more intuitive in the making of it. In this sense the external world encouraged the internal world.

A: What advice would you give to a graduating artist?

JB: Whenever I’ve tried to make work that I think other people would like, it’s always felt a bit forced, a bit dry and mechanical. The really exciting stuff seems to flow the more you tap into your own way of seeing, and this is what I would encourage; both with the art work and within personal life. I was given some advice a couple of years ago; “rather than change yourself to fit in to how you think others will love you, be yourself and see who comes in to your life to love you for that”. I think this is great advice for the art-making process too.

A: Some people might argue that if you’re an artist, you don’t need to go to college to study it- obviously you did! What do you say to people who think that?

JB: One of my favourite artists is Henry Darger, who didn’t study art at college, lived alone and preferred to spend time with himself. Upon dying, his landlord discovered his flat was full of watercolours and drawings of this other world Darger had created, with girls in uniforms rebelling from the adults that controlled them in stirring situations of group behaviour. Now he is in museums throughout the world, and because nobody knew he made this work, that other people’s eyes weren’t important for the creation of it, and that it was a conversation with himself shows how the internal world can matter more to a person than the external world.

I can relate to this because I like to make my work in my own bubble, as an introverted process – through following my own intuition, rather than attempting to think what other people would like. It’s important to me to make the work through my own eyes, yet regardless of this, the eyes of others have been incredibly important in looking back at the bubble from another place.

I feel that to be an artist you don’t have to go to college to study it, yet being at UAL and the RCA fueled my thoughts in surprising ways, inviting perspectives from different angles, questioning what it is that I am doing, and why. And for this I feel that my practice as an artist has been pushed and challenged beyond expectation through my time in the institution. The facilities, the lectures, and above all the people I have met have been invaluable in the development of the ideas.

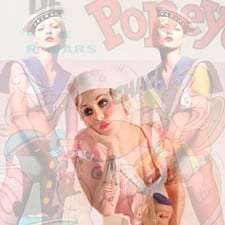

A: Your work often combines multiple images, what was it that drew you to that technique?

JB: The montage is a way of clashing alternative visual realities and time frames, of juxtaposing different ways of seeing. Through making in this way I’m reminded of growing up in the bubble of the family home. Only as I grew older did I have the opportunity to see outside the version of normal I was socialized into, and realize there were so many other versions of normal out there that cancelled each other out in the realisation that nothing is normal at all. From this I entertain the thought that much of culture is artificial, and gets in the way of seeing what’s actually there. My parents and I have different ways of seeing the world, and like the work it encourages me to see our relationship also as a montage of different time frames and ways of seeing.

A lot of the other photographs appear as if they have been montaged, yet upon closer inspection are realised to be more real than first thought. Some scenes take weeks to create, and in their peculiarity appear to be artificial, montaged or photoshopped, and I love the suspension of disbelief this can create. It takes me back to being a child, before I was socialised, and before I knew what was real, and what was fantasy.

A: Your series Ancestral Home recently ran at Simon Oldfield, London, you take inspiration from your family circle- how did you relay this in your work?

JB: My family have played an integral part in socialising me into who I am as an adult – yet it is this socialised self I so often attempt to escape and think outside of – to look at the world and back at myself with fresh eyes.

For the past year I have been working with a laboratory in North London for the main piece in the show, Dummy; where a small house has been grown out of human cancer cells. This idea has emerged through thinking about parallels between the home and the body, and the home as a metaphorical body. Many examples spring to mind. I realised recently that whenever I’ve had a bereavement or long-term relationship break-up, I’ll change my room around, get rid of old things I don’t need anymore, re-arrange what remains.

Towards the end of my Grandmother’s life, it became increasingly hard for her to clean and maintain her home. The walls becoming ever more yellow with cigarette stains, they became inescapably linked to her lungs. Whenever I would visit, it would be like walking in to her body, and a daunting reminder of its deterioration. The home and the body are intimately entwined. The psychoanalyst Darian Leader also once observed that the words people use when their homes have been intruded, vandalised or burgled are startlingly similar to when their bodies have been violated.

The body has a psychological history of it’s own, where our mental state becomes reflected in our physical selves. The state of our minds influence how we make and shape our surroundings; our communities, our homes, and so too do our surroundings, communities and homes influence the way that we think, and the way that we think physically manifests in the body. A reminder that we make our environment, and our environment makes us.

The title Dummy, refers to a surrogate human body or body part such as a baby’s dummy, or a crash test dummy. It’s referring to something that isn’t there, as a stand-in. The incubator also artificially mimics the body, and references something that isn’t there.

A: What are you future plans?

JB: I’m really excited about a new body of work I’m focusing on. Activities so far this year have involved casting my parents’ kitchen in flesh coloured latex, knitting conjoined clothing, giant unpicked tapestries, pregnant children made from clay, animatronics, and collaborating with stem cell scientist Anthony Hollander.

More exhibitions are planned for England, France, Holland, Italy and Australia, and updates of future plans can be found at www.jonnybriggs.com/whats-next.

Credits

1. Envisionaries No. 11, Jonny Briggs, courtesy of the artist.