Behind glass doors, in rows on little wooden shelves; spread across rooms, on plinths, on mantelpieces, suspended from ceilings, objects – from sea-creatures to meteorites, from strange bones to unidentified mushrooms, from mummified cats to fragments of ancient pottery – line the “cabinets of curiosities” of history. These objects – however colossal, however miniscule – have for centuries represented the progression, boundaries and limits of our knowledge: little fragments of the world that we are forever attempting to define and understand.

Curiosity: Art and the Pleasures of Knowing, an exhibition curated by writer and UK editor of Cabinet magazine, Brian Dillon, has recently seen the seaside gallery, Turner Contemporary, transformed into a labyrinthian cabinet of sorts. In a sometimes strange, sometimes enlightening and eclectic collection of exhibits, it combines contemporary art works with historical artifacts and specimens from natural history. Aesthetica visits to meet Dillon and discuss the ideas around the show, a week before the exhibition opens, on the day that one of the most important, exciting and perhaps most surreal of exhibits is due to arrive: the Horniman Museum’s overstuffed Walrus. “The walrus is a great example of where discovery overlaps with speculation and absurdity,” Dillon explains. “Most zoologists and taxidermists at the end of the 19th Century had never seen a live walrus specimen or even a photograph or drawing of a live specimen. In this case, the walrus was shot by a Canadian hunter called James Hubbert and then stuffed by people who didn’t realise that the folds were supposed to be folds: that they weren’t supposed to just carry on stuffing until it was completely full! So, eventually, it turned into this great, fantastically bulbous creature.”

There is a strand that runs through the exhibition that seems to highlight the often-stunted end of discovery: the boundaries of knowledge. Of course, with the walrus, the scientific accuracy of the object is stunted by the stretched and expanded deformity it suffers from being over-stuffed. A series of photographs by Katie Paterson also similarly reflects the boundaries of discovery, but in a perhaps more deliberate manner. “History of Darkness by Katie Paterson is a series of images taken from observatories and amateur astronomers around the world, and each one simply shows a black portion of sky; they’re all, simply, small rectangles of pure black, all exactly the same,” Dillon explains. “There’s something very pure and poetic about Katie’s work. What it reminds me of is the sheer strangeness of discovery… that it’s not just about saying ‘this is what we know.’ It’s also about representing the moment where we don’t see, where we don’t discover… where knowledge ends.”

Our conversation spins off on a few tangents, but soon returns to the mysteries of discovery and knowledge. “Do you know about the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death?” Dillon asks, sipping on his tea. “In the 1940s an American heiress, Frances Glessner Lee, made these dollhouse-sized dioramas, each representing a real death – some murders, others suicides or accidental: corpses in bed, blood on the walls and so on. And they used – and still do use – these constructions to train detectives in Baltimore. So, we’re exhibiting images by Corinne May Botz: really beautiful photographs of these scenes. And, of course, they hold secrets: secrets held by the Baltimore police department. I couldn’t even tell you what’s happened in the scenes, because I don’t know myself! So, in this work, there is another, different dimension of this sense of not knowing… and never knowing.”

Despite the obvious – though probably accidental – strand on the limits of discovery, there is, notably, little in sense of order and categorisation in the exhibition: “What is important is that it’s not an archive or chronology of curiosity. It’s not an exhibition about science and art in any direct way either; we were very much more interested in a kind of oblique, suggestive or intuitive relationship between all the objects we have chosen to exhibit,” Dillon says. “Our starting point was eclecticism: in some ways a reflection of the variety, strangeness and eccentricity of the historical cabinet of curiosities.”

“We’d been having conversations for a while with Rodger Malbert about Cabinet Magazine doing a show for Hayward touring,” Dillon continues. “And we decided, rather than having an exhibition focus on a specific theme, as the magazine does, on hair or dust or laughter, it was actually better to look at the core sensibility of the magazine, which is curiosity… Sina Najafi who set up the magazine in 2001 always talks about curiosity as a starting point – not just the historical cabinet of curiosities, but a kind of notion of contemporary interdisciplinary: the real sort of capacious curiosity in contemporary art. He wanted a magazine that would not exactly fully reflect curiosity and art, but would inspire artists and create curiosity. The exhibition, in its creation, came to be as unpredictable as when creating one issue of the magazine… so we kept finding that we were kind of surprising ourselves as we were making the show; hopefully, the show itself will actually surprise visitors too.”

As our conversation ends, the walrus arrives. The staff crowd around as it appears at the back entrance in its big wooden crate and follow it, in a procession, as it is wheeled to its new room. There is certainly a sense of awe surrounding this unconventional delivery. As it is revealed, wearing a strange protective duvet coat and headdress, the small crowd murmur, gasp and giggle. When I eventually leave, the most important and most celebrated item of Dillon’s cabinet has taken its place on its plinth and is having its feet hoovered and tusks polished.

I return to attend the private view a week later and the walrus is surrounded by visitors and a huge collection of other curious exhibits: Robert Hooke’s famous close-up of a flea from his Micrographia, Durer’s rhinoceros engraving, the exquisitely realistic and perfectly-formed glass models of aquatic creatures by Leopold and Rudolph Blaschka, artworks by Tacita Dean, Richard Wentworth, Jeremy Miller, Turner, Da Vinci… As I meander through all the rooms and corridors, happening upon moments of intrigue, mystery, strangeness and wonder, I am reminded of a brilliant word that Dillon had used during our conversation last week to describe the exhibition; taking a bite from his lemon shortbread, with his tea in one hand, he had said, between mouthfuls “I want the exhibition to be… to be flummoxing in a way… I want it to inspire, yes… but to also… flummox.”

Part of me experiences just this – a flummoxing bewilderment in which it becomes clear just how little I know, how much others know, how much the world knows and how little the world will ever know – however, part of me too becomes intoxicated by the potential for learning imbued in every single object on show. My thirst for knowledge and understanding – my curiosity – pleasurably takes over.

Curiosity: Art and the Pleasures of Knowing, until 15 September, Turner Contemporary,Rendezvous, Margate, Kent, CT9 1HG.

Claire Hazelton

Credits

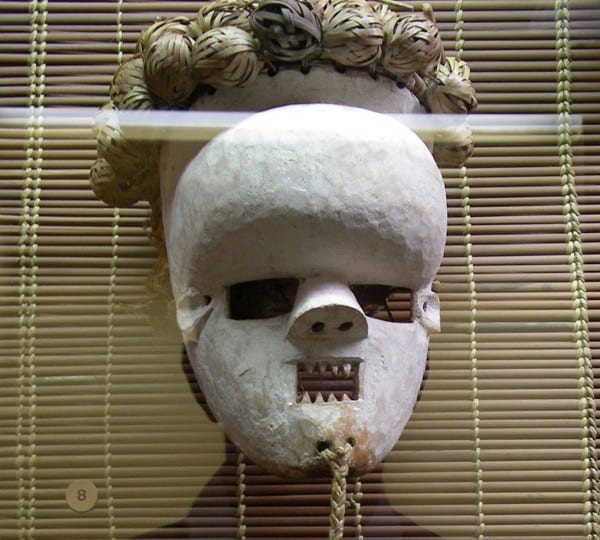

1. Jeremy Millar-Mask Self-Portrait Three, courtesy of Turner Contemporary.