Celebrating its 30th Anniversary, Forced Entertainment has spent the last three decades pushing the boundaries of contemporary performance. Founded in 1984 by six recently graduated artists, the theatrical group have created numerous productions that have continued to play with language, staging, costume, lighting, humour, narrative sound and the very nature of a performance piece. Artistic Director Tim Etchells is also a solo artist and has seen his work exhibited internationally. This year he is officially Artist of the City of Lisbon. He speaks to Aesthetica about upcoming performance, The Notebook, and his ability to sustain a theatre company for 30 years.

A: Forced Entertainment has been running for 30 years now, within that time there must have been numerous other theatre companies open and close, what is it about your organisation that has made you so successful?

TE: I think we were lucky, in a way. We were friends who met at University. We made various things together whilst studying and from that experience we had the intuition that there was a dynamic conversation, that there were projects we could make together, questions that we could approach. That intuition proved to be correct – that was lucky! We could just as easily have been wrong. I guess the other thing that’s important is that we have taken risks. We’ve allowed ourselves to change the ground of the work – taking projects into different areas, aesthetics and concerns. That’s meant that what the work is, and who we are has changed – we’ve challenged ourselves as well as our audiences.

A: When working on a new production, how do you develop new ideas and keep the momentum of the company going?

TE: Mostly, I’d say, we make things by spending a lot of time in the same room together; by doing things in that room. This requires time and a group of people prepared to be there. Working collaboratively for us means just that everyone inputs and that no single vision holds sway. We all listen, adapt, compromise and mix them with ideas from other people. We start from an idea (and practise) of collective work; the performance we are going to make will be made by everybody. Everybody will have ideas for text, themes, images, music, costume, set and structure. On a daily basis everyone’s ideas will be met, challenged and reinvented by those of everyone else. The performers are a part of this process and so too is anyone with a title of some other kind, be it writer, director, set-designer or composer.

A: How do you go about ensuring everyone is involved in the process of production?

TE: No one brings anything too completed to the process. I might bring: notes, scraps, half-thoughts. I might just bring some ideas for structures. In any case I bring things that other people can add to, change, break or even complete. It’s expected that other people will bring incomplete stuff too. Everything changes and mutates in the process of the work and I think it seemed pretty “natural” to us to work in this way. Performance is inherently this collaborative, cross-fertilizing process, especially if one is interested in making things that do not privilege the written word. I think this collective process makes the final product stronger – in the sense that the ideas explored for a performance are subjected to a pretty serious critique by everyone else! So anything that does make it through has usually had to adapt, fight or die. The group process also means that the pieces are a meeting point for a lot of different intentionalities – there’s no single author with a very pure vision. Instead there’s a space in which quite different visions meet – I think you can very often see that in the work.

A: What do you think are the biggest challenges for theatre companies starting out today?

TE: I think the financial pressures are more severe than when we began. If people are starting out after their studies as we did then they’re arriving with student loans and other debts already in place – I think that installs a certain caution into the choices people make and we didn’t have that. We started in a recession, an economic meltdown rather like the present one – but the way we survived on the edges of the benefits system when we started our work would not be possible now. That space is too regulated, too policed, too arid and so younger groups starting out have to be much more fluid and resourceful. In fact that’s one part of this particular age – early 21st Century – the marketplace is increasingly modular (short term contracts, zero hours, itinerant workforce, globalised) and in a strange way the arts field presents an advanced, even exaggerated version of the same thing. I’m not sure that collectives of the kind that Forced Entertainment represents are really possible or plausible in economic terms anymore – it’s been very hard for us to sustain, and always has been a tricky model. But the reality of the economic landscape now is much more stacked towards people working alone, as independent free agents, making temporary collaborations, flitting in and out of things, flowing where the money and opportunity is. There are a few partnerships I guess, but being part of a permanent group – six people – is very likely too heavy for this moment, too solid. It’s all about networks, distribution and flow now – radical but at the same time exactly in line with how capital wants things organised.

A: The Notebook, based on the book by Hungarian writer Ágota Kristóf, will be showing at Sheffield Theatres this October before touring the UK in 2015. What made this text suitable for a Forced Entertainment performance?

TE: Most of us read The Notebook in the late 1980s and early 1990s I think, and we were very struck by the vividness and intense visuality of the language. It had a quality shared with the texts that I’ve been developing with Forced Entertainment; an approach to language that’s very simple and visual, very much about language making images appear, or about language making action unfold in the mind of the reader – that’s something we’ve been playing with in performative terms for a very long time in other projects. So in that sense it seemed very relevant to me. The other thing was that it had this extraordinary quality in that the book is narrated by two people, twins – who recount their whole story as “we”, refusing to articulate themselves as separate individuals or as “I”. The “we” of the text in the book is tied to the twins refusal of a separate identity. It’s a pretty uncanny narration and all the time you’re reading you’re aware of the impossibility of the “we” they propose – this “two people as one”. But when you put the same thing into performance the uncanniness shifts – it’s material, it’s concrete, it’s not the abstraction of a text on a page. I mean – it’s not an idea anymore, not something proposed in language – it’s a fact, two people, two voices. It’s immediately theatrical and dynamic and it’s performative in a very simple way. That was definitely one of the attractions to the text.

A: What do you think is special about this work?

TE: It’s a text that places a lot of responsibly on the spectator – you have to make judgements all the time, because the text refuses to make them. Situations, facts, events and images go by and all without explicit judgement – the spectator really has to deal with everything, and I love that; it won’t tell you what to think. Of course that’s got a close relationship to what we’ve been doing in our performance work for a very long time, in that we want to create works and situations where audiences have to make their own minds up, where they have to figure it out, where they have to join the dots. So, The Notebook was perfect for us, because it already belonged very much in that same territory. Finally, in part The Notebook is about the way that situations – in this case a war and a culture – brutalise people and how these situations force people, press them into strange shapes. I think it’s very relevant because I think although we’re not in a war right now, not exactly, not at home at least, we are nonetheless in a situation where through various means, because of Islamophobia and xenophobia of the current political scene, because of the economic downturn, because of ongoing conflict situations like Afghanistan and Iraq, because of the so called war on terror, because of the surveillance culture, because of the kinds of mass surveillance that are possible now and have been perpetrated in the last 10, 12 years by the Americans and by the British and probably by the others too, because of all those things the landscape we inhabit has become toxic and brutalising in so many different ways. And that toxicity writes itself into us in very violent ways I think – and I think in the broadest sense, that’s one of the things that The Notebook is about.

A: The Last Adventures is also making its UK premiere – and its only UK dates are 1-3 October at Warwick Arts Centre as part of Fierce Festival; do you find different audiences in different countries respond to your work differently?

TE: We’ve presented work in many places across the world – Japan, Australia, USA, Canada, Lebanon, Columbia, Argentina, Korea and so on, as well as pretty much all over Europe, but I don’t think the variations in reception are especially based on country – it’s much more complex than that. More often responses are about the confidence and openness of particular cities or audiences – a lot of things feed into that, but where there’s a festival or a venue that has been working over time to build audience and context for new work then I think we always feel the benefit of that. So, Fierce Festival in Birmingham and Warwick Arts Centre where we are presenting The Last Adventures are really great hosts in that sense. I guess the other thing – in terms of how the work travels internationally is that we tend to use very simple, pretty straightforward language. It has its poetic aspects but there’s a core of simplicity and directness to the language we use, as I was saying in relation to The Notebook. That really helps the work to travel well. We’re also working with a very bold visual and sound palette. An initial starting point was something we’ve talked about in Forced Entertainment for a long time; which was the idea of drawing on events from fantastic or epic stories. We had in mind a wild mix of things; from journeys to the underworld or encounters between the living and the dead to ideas from fairy tales or science fiction – magical landscapes, objects that come to life or a war between humans and robots! Text wise I was thinking about collage, about jumping from genre to genre and visually I was thinking a lot about choruses or crowd scenes. I was collecting images from amateur productions which showed pantomime choruses, with groups of school kids who were dressed as peasants or soldiers or skeletons or mermaids. Henry Darger’s epic drawings and collages of battles and bizarre scenes with hundreds of characters were in the back of my mind too. In all of it we were drawn to the idea of the stage as a space for image making on a large scale, thinking about a chorus, a crowd, a mass of people rather than individuals.

A: You collaborated with sound artist Tarek Atoui on this piece too. How has the impacted The Last Adventures?

TE: Tarek Atoui’s work uses sound samples as modular fragments for algorithmic recombination, and that made a clear connection to our theatrical interest in making narratives made from fragments of existing stories. The music is a really important part of The Last Adventures and again it definitely helps in terms of the piece communicating internationally. Something I’d experienced when I first saw Tarek’s work when we first met a good few years ago, was an idea about fragments – about working not with a complete object but a set of objects, (whether that’s images, texts, stories, sounds) that have been shattered or broken in different ways. That’s something that in my work with Forced Entertainment and as a solo artist, I had been interested in and pursuing for a long time. I’m thinking about how one works with fragments and how one composes new things dramatically, narratively or musically from the ruins of existing things. It is a kind of process of recycling and construction and I guess I felt there was already a strong connection there to what I knew of Tarek’s work. Tarek also shares with Forced Entertainment a big interest in structured improvisation and the possibilities that it affords for generating surprise shifts in performance energy and content. For The Last Adventures, Atoui conceived a musical structure for the work in which his written and recorded score would be accompanied and remixed for each live presentation by a new sonic collaborator. So far we have had improvised contributions from Atoui himself, Uriel Barthélémi, percussionist, Mazen Kerbaj, trumpeter and for Warwick the shows will feature one of the founding fathers of Japanese noise music, the multi-instrumentalist and electronic musician and composer KK Null, as special guest.

A: What do you have planned for next?

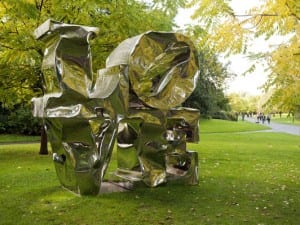

TE: I have a lot of solo things going on at the moment as well as the work with Forced Entertainment. I have a large new neon piece in Folkestone as part of the Triennial, and another that’s just been installed in Leeds as a public sculpture commission for the Algernon Firth Building. I’m busy preparing new work for a group show at Hayward Gallery in London called Mirrorcity (14 October – 4 January 2015) – posters and other text works and another neon, which will be visible from Waterloo Bridge. I’m excited about that. In the more long run I’m working with Forced Entertainment on a performance for children. That’s certainly a first. It’s called The Possible Impossible House and it’s opening at The Barbican on 17 December for 20 performances. It’s really good to be working away from the usual rehearsal space and the collaboration with visual artist Vlatka Horvat – who is making the projected images that feature throughout the performance – is really bringing something new and exciting to the project, too. The project and the collaboration are both part of our feeling out the possibilities – pushing ourselves to work in new ways. It seems that’s an important part of what we do, even after 30 years. We’re also preparing for a couple of livestream events – one from Berlin, 18 October, 5 – 11pm GMT; and one from our home town of Sheffield – more on that to be announced.

Forced Entertainment 30th birthday UK activity includes, The Last Adventures, 1-3 October, Warwick Arts Centre, The Notebook, 10-11 October, Sheffield Theatres, Speak Bitterness, 18 October, That Night Follows Day, 29 October, Warwick Arts Centre, Quizoola! 21-22 November, Millenium Gallery, Sheffield and The Possible Impossible House, 17 December, Barbican Centre, London.

Credits

1. Is Why The Place – Folkestone Triennial. Courtesy of Forced Entertainment.